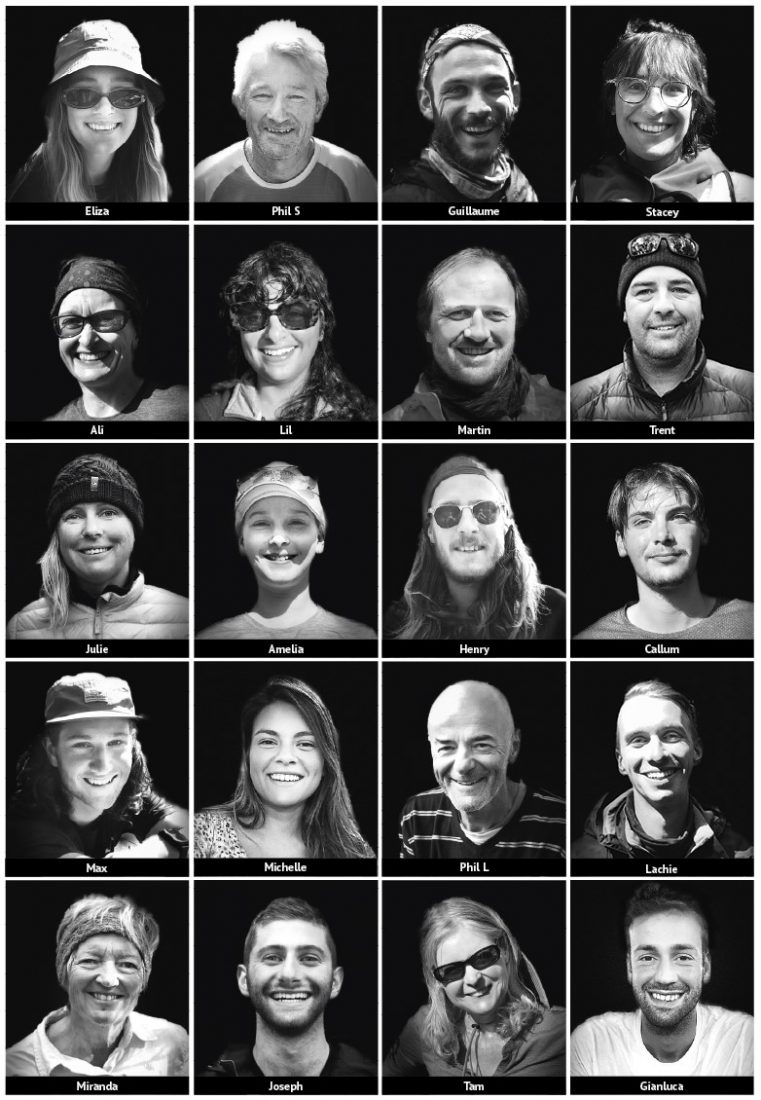

The People of the Trail

Walking the Overland Track, Joseph Friedman discovered one of the outdoors’ true joys: those you meet along the way.

Words: Joseph Friedman Images: Lachie King and Joseph Friedman

(This story originally featured in Wild #181, Spring 2021)

Before the sun came down on 2019, when a soon-to-be crippling pandemic was still a yet-to-be discovered virus, three friends and I set out for eight days on the Great Ocean Walk. We spent a week hiking through Great Otway National Park along Victoria’s coastline. We talked and joked and laughed until our voices were hoarse. We cooked and drank together, and we barely left each other’s sight.

Each morning, often before we had packed up our tents, a woman in her 30s set out for the day. She said she’d recently completed the 14-day Larapinta Trail by herself, and here she was again, on a multi-day hike, alone.

Some nights when she saw us she asked to join. She told us she sometimes felt lonely, but that occasional loneliness was a cheap price to pay for her love of hiking, and her friends weren’t interested in joining. Plus, the solo adventure meant the chance to meet new people.

My friends were sympathetic. I was intrigued.

I realised that the four of us had spent every minute on the trail as a group, in twos or as a four but never alone. So after lunch on our final day, we set out one-by-one to find a solo experience, if only for an hour.

That hour wasn’t life changing, but it was different. It was slightly unsettling, but also peaceful and freeing, and I yearned to repeat it.

My plan was to start slow: a day in the Dandenongs, a night in a drive-in campsite, then eventually an overnight hike. I wasn’t ready for the big league.

But when the virus came to town and our lives shrank to a five-kilometre radius, all my plans, however enticing, couldn’t justify a $1,652 fine. Instead, I turned to books, and like many adventure-deprived university students before me, I discovered Christopher McCandless of Into the Wild and my yearning grew.

A year later I took the plunge and set out solo on the Overland Track, perhaps our country’s finest trail.

If you’ve ever hiked alone or even contemplated it, you might recognise the self-doubt: What if I’m injured and there’s nobody to help? What if I get lonely and stuck inside my head? Can I really carry all that weight myself?

But over the course of a year, I had become convinced. Convinced by the freedom, the time for contemplation, for complete immersion in a setting without distraction. And convinced by the opportunity to meet new people—the people of the trail.

There’s a certain type of person whose idea of a holiday is to walk for a week with nearly a third of their bodyweight on their back. It is a person comfortable with putting their phone away and simply looking up. More than comfortable—it is a person who thrives on it. It is Lachie and Eliza and Guillaume and Stacey and Henry. It is the twenty of us on the Overland, couples and families and solo travellers, who played a spontaneous game of trivia on a wet Friday night, and who hiked and swam and ate together for an unforgettable week earlier this year. And it is the dozens of people who book out the Overland Track and countless other trails months in advance for every day of the summer.

The archetype of this outdoor adventurer is young but seasoned, handsome in a rugged sort of way, fit with lightweight, dry-fit gear—the kind of person who graces a Patagonia billboard. On our trail it was a young couple, George and Pru, who belonged on the billboard.

The attractive duo worked as a team, first to depart each morning and first to set up their tent each night, carrying foldaway solar panels and all the newest gear. On Day Three, they decided to ‘do a double’ (hike two days in one) and we never saw them again.

“Where else do we get to spend substantial time with people of different ages, from different places, with different backgrounds?”

Of the twenty who remained, not one fit the archetype. Take Phillip Lawson. South Australian Phil. Born and bred on the banks of the Murray, Phil is 59 years old, bald with grey stubble and oversized clothes hanging off his skinny frame. He’d never done anything like this before. For thirty years, Phil was a postal worker, climbing slowly up his local store’s managerial ladder until he reached an indefinite plateau. After a quick stint as a bus driver, Phil became a correctional officer at a minimum-security prison in Cadell, a job he loves. “It’s the best kept secret”, he says. One time, he worked 59 days in a row: “I don’t have much of a life, so I take on extra shifts.” He was joking when he said this; nonetheless, he’d earned this holiday.

Hiking solo on a multi-day trail with no mobile reception, I was well-positioned to listen. And Phil was happy to talk. He had an inexhaustible stock of jokes and he starred at the trivia night, easily the MVP. Here was a man who had lived a quiet life and had never spent a night on the trail, let alone for a week in the Tasmanian backcountry. Phil listened to us talk about our gap-year experiences and other adventures, and he told us he wishes he’d done the same. But Phil was here now. After months of training, he had made it, and he was already planning the next one. It’s never too late to start.

Sure enough, four months later we each received a message: Phil had won a prize at a hiking expo—a cottage in Kuitpo, South Australia, with space for nine, and eleven more in tents. We were all invited. Sadly, the latest lockdown meant that only the locals could join, but the next adventure is already in the works.

Was there a Phil on the Great Ocean Walk back in 2019? I wouldn’t know. Unless a solo hiker asked to join the four of us, we kept to ourselves, missing a rare chance to connect with new people. Where else do we get to spend substantial time with people of different ages, from different places, with different backgrounds? Back home, our lives are full of friends, families, colleagues; we are always busy, moving, hustling. We exist online and fast paced. The trail, however, invites us to stop. It asks us to be curious. To meet people like my new friend, Guillaume.

My trip on the Overland Track lasted six days; Gui, when I met him, had been adventuring for nearly three years.

Guillaume and his backpack arrived from France in early 2019. While most backpackers returned home as borders shut, there are still many thousands who remain in Australia. You’ll find them working on farms, living in hostels for months at a time, or hiking alone all over the country, like Gui.

The indefatigable Frenchman has barely spent a night under a roof for two years, and survives by planting trees, teaching kitesurfing, and trading cryptocurrency, including atop mountains in the Tasmanian wilderness—the only places on the Overland with a phone signal.

“Even in our sameness, each of us is completely individual—something that became clearer

as the days went on.”

Guillaume’s smile is emblazoned onto his mouth; his tan and enthusiasm were permanent. For Gui, even mundane things like breakfast were a delight: “Every morning before you brush your teeth, your mouth … it is like a virgin.”

At the end of Day One, when we still barely knew each other, Gui asked me: “Jo, will you climb up ze mountain tomorrow for sunrise?” I happily agreed, hiking, scrambling and then climbing vertically up the slippery rock of Barn Bluff mountain at 4:30 the next morning, torches off … “your eyes will adjust!”

When we reached the top, we sat and shivered together, eating small pieces of chocolate as we watched the sun light up the new day. For me, this was an extraordinary moment. For Guillaume, these moments are almost daily occurrences.

I found myself envying Gui and second guessing my own more prosaic choices. I had to remind myself that a life spent almost entirely outdoors is a rare one. For the rest of us on the trail, the same elements of life waited at home: school, work, family—responsibilities. And yet even in our sameness, each of us was completely individual—something that became clearer as the days went on and I spent time with my hiking companions.

Take Lil and Henry.

Lil, in her early 20s, is more books than wilderness. “I hate hiking,” she told me, preferring to discuss such topics as the Nigerian-American writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: “Her feminist epistemology is amazing.” Yet here was Lil on a six-day hike with Henry (“he dragged me along”), whom she met on Tinder only a few months earlier.

Henry, in his mid-20s, is from Albury-Wodonga. He wears his waist-length hair in a headband and speaks in a laconic Aussie drawl. His gap year was five gap years, working in Australia and then living out of a van in North America. He speaks Spanish and French and wants to learn more. And he’s intensely curious about everyone around him.

Lil and Henry simply clicked; it was a delight to be around them.

Henry was frustrated at the class segregation that defines Australia’s education system. He described a system where disadvantaged students are increasingly concentrated in some schools, and advantaged students are increasingly concentrated in others. This social segregation has seeped into our post-schooling lives, entrenching a society where we surround ourselves with people like us. And it’s one of the reasons being with the people of the trail is so special.

Because with the performative busyness of everyday life, it’s rare to walk past someone crossing the street who turns to you and smiles or acknowledges your presence. And while we might briefly encounter dozens of people from different socio-economic backgrounds every day, we rarely glance at them, let alone stop to engage.

But out on the trail, it’s a hiking faux pas if a fellow hiker doesn’t say g’day. Six days solo on the Overland Track, with only nature to distract me, I got to know so many different people.

I learned from a dairy consultant, Phil Shannon (the other Phil), about how to be a dad. The self-deprecating country Victorian came with his two young-adult children, Eliza and Max, making them cringe on repeat with a never-ending supply of dad jokes. He hid behind bushes to scare us, and dunked his head in cold water to make us laugh, never taking himself too seriously, showing interest in everyone, and always putting his kids first.

Phil told me to “focus on the journey, never the destination.” He said, “It’s so easy to miss taking time with your kids when they’re growing up,” and that his greatest achievement—above all else—is to have invested in spending time with them. Watching Eliza and Max, seeing their love for the outdoors and their independence, it was clear that Phil’s investment had paid off.

“My experience with the people of the Overland was not unique. One hut ahead of us hiked another 24, and one hut behind us the same. Today, and every summer day, 24 people will set out.”

Another couple, Stacey and Martin, offered lessons about savouring the present. Stacey and Martin were unbothered by the time it took to get from A to B. They woke up late and enjoyed their porridge. They walked slowly, stopping often but never for a photo. Instead, they took out their watercolour pencils and drew what they saw around them: a close-up of a small purple flower blossoming out of a sea of button grass, a sweeping mountain vista, plunging waterfalls and dramatic peaks. Their clothes were worn-in, their gear well-used, their meals self-dehydrated. Stacey and Martin were peaceful and content, and they helped make sense of what’s really important.

And finally, I learned from Tam, a middle-aged mum who didn’t think she could make it. One night she was ready to drop out, and the next day when we reached the hut, the ranger told us Tam hadn’t continued. Her son Callum was alone at the hut, crestfallen. But then Tam showed up. Callum was thrilled. And Tam made it all the way through to the end.

These portraits depict unusually kind and curious people. But my experience with the people of the Overland was not unique. One hut ahead of us hiked another 24, and one hut behind us the same. Today, and every summer day, 24 people will set out from Cradle Mountain, and six or so days later they’ll return home.

In each of these huts there’s a notebook—a journal of sorts, for the evening’s lodgers to reflect or to send a message to the next day’s arrivals. You can read a grumpy man’s gripes about “so many non-Overlanders here with so much energy … by far the noisiest place to stay.” Mostly, however, these are books of wonder, filled with tales of exhausted but satisfied hikers reflecting on their experiences.

These people are special because the people of the trail are special. Young and old, they come from all over, looking for adventure, to dwell in the present and feel deeply alive.

On our third night on the trail, the morning shower had become a major rainfall event—almost 100mm would fall in the next few hours.

The sound of the storm became deafening, and the walkway quickly dissolved into mud. But the twenty of us, warm and dry, were unperturbed. I had spent that day walking with Lachie King, an enthusiastic 25-year-old like me who quickly became a close friend. In readiness for the storm, we prepared a trivia night.

Inside the hut, a familiar scene played out. In teams of four or five, the contestants crammed into wooden benches across long tables. They sat with food and drink, pen and paper, applying their niche knowledge to each question.

“List the top five countries in order of land mass.”

“Who wrote The Shining, and who directed the movie?”

The questions were varied but conventional. Music, politics, geography, pop culture. Something for everyone.

And yet this could hardly be called a conventional trivia night. Lachie and I had never before hosted trivia. Most of the teams barely knew their own teammates, and only found out about the game an hour before it began. And once the night was over, we got up from our benches, hopped into our wooden bunks, and slept, the warmth of shared experience in the air.

The next morning we woke to the songs of birds perched on tall eucalypts. We ate our porridge, packed our bags, and set off for Day Four of the Overland Track. Another day on the trail.

CONTRIBUTOR: Joseph Friedman is a wannabe adventurer with a habit of getting lost, no matter the location. He works as a full-time lawyer in the day, and dreams of his first thru-hike by night.

If you liked this piece, you should subscribe to the print mag. Only a fraction of the great stories we run in the mag make it to our website; if you want to read them, head to subscribe.wild.com.au.