Around the Hallingskarvet

A team of Aussies and Kiwis head to the ice planet Hoth (aka Finse, Norway) for a two-week sufferfest in Hallingskarvet National Park. The goal is preparing them for an upcoming 1500km Antarctic expedition; as they discover, the gale-force winds, whiteouts and all-round burliness of Hallingskarvet proves a perfect training ground.

Words: Jack Forbes

Photos: Kelly Kavanagh

A fierce battle between Storm Troopers and the Rebel Alliance erupts as we prepare to venture into the frozen landscape surrounding the village of Finse in central Norway. At 1,222 metres, Norway’s highest train station provides the only access to the hotel, hostel and handful of cabins which make up the village. While popular in summer for mountain biking and hiking, it is the frozen yet accessible backcountry terrain which bring our ten-person team of Australian and New Zealand military members to the perfect preparation ground for a 1,500 kilometre coast-to-coast crossing of Antarctica.

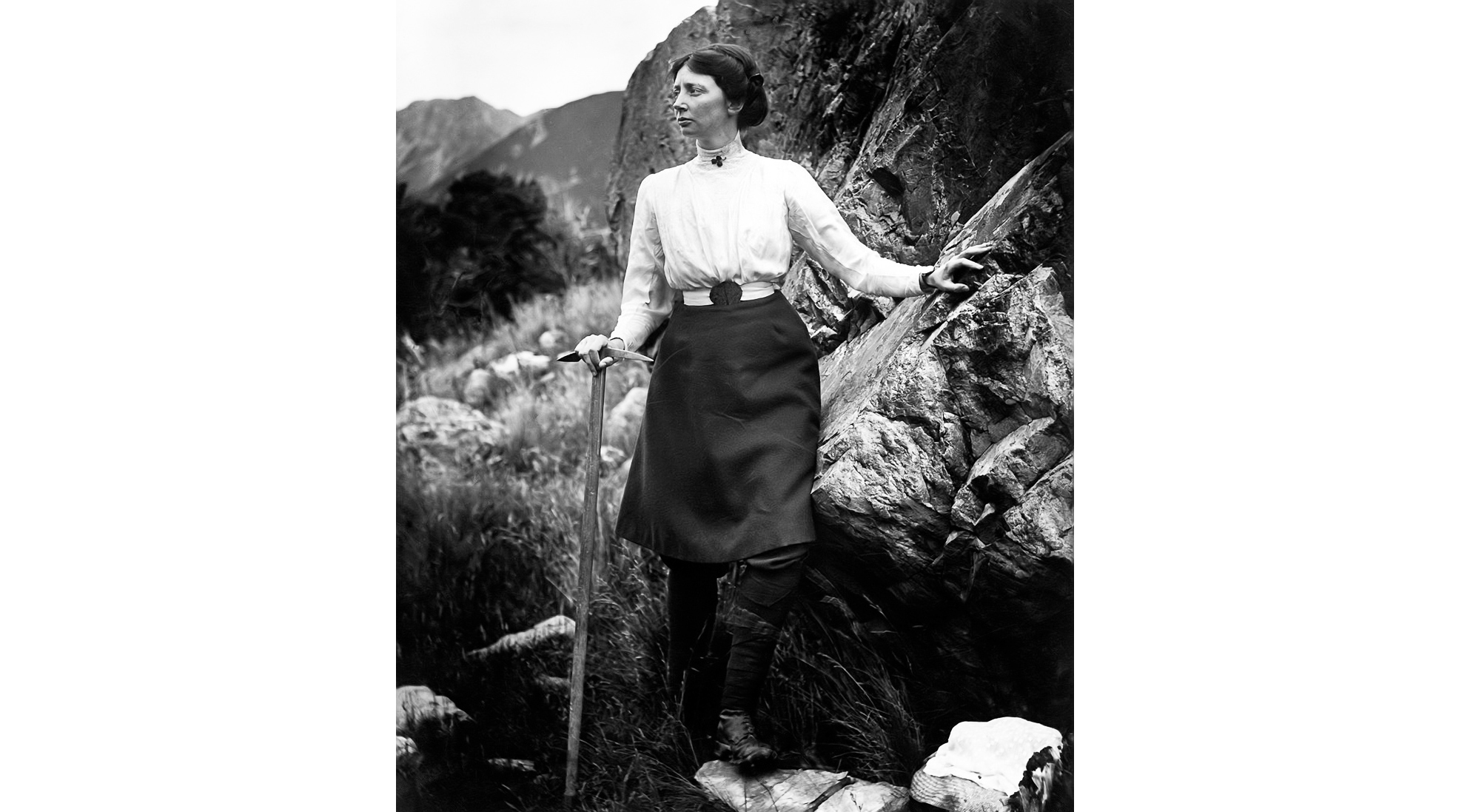

There is no better training ground for the harsh conditions of the polar regions – the village was used as a base for expedition training by Roald Amundsen, Robert Scott, and Ernest Shackleton for their polar explorations. Above the frozen lakeside, a stone plinth stands in the snow as a stark memorial to Scott’s ill-fated journey.

In surreal contrast, the tiny village is humming with the sounds of light sabres, snow-speeders and Wookies. It is the fortieth anniversary of the filming of The Empire Strikes Back, in which the surrounds of Finse served as the ice planet Hoth. We are privileged to meet some of the original crew, including the art director Alan Tomkins, who, after hearing two of us are from Perth, is curious as to whether we also know Hugh Jackman, whom he has worked with recently. Unfortunately, we do not.

As the fight for Echo Base dies down, we leave the village behind and head into the rugged landscape of the Hallingskarvet National Park, dominated by the sheer granite walls of the mountain range after which it is named. For the next two weeks, we will haul sleds packed with our supplies and equipment around the range, refining the skills of polar travel required to survive in this unforgiving environment.

For many of us, this will be the first time towing the heavy sleds loaded with the tools required to survive in the extreme cold, and a significant change from the temperate climate of Australia. Fortunately, we are supported by Hannah McKeand, a polar legend who has schooled our team on the wisdom of safe polar travel. Hannah has covered over 10,000 kilometres sled-hauling in the Antarctic alone, having completed a world record number of polar expeditions from the coast to the South Pole.

“The trick is to take one day at a time – if that is unbearable, then one hour at a time. Or when even that seems impossible, one minute at a time.”

Over the next two weeks, we will develop the art of eating, sleeping and skiing on the ice, melting snow for cooking, pitching tents in ravaging winds, and, of particular importance, the perfect technique for a toilet stop in blizzard conditions, taking care to avoid the horrifying potential for frostbite in a delicate area.

Initial days are met with blue skies and clear nights as we haul ourselves upwards through a pass in the mountains to circumnavigate the Hallingskarvet range. Warmer days and difficult terrain bring their own challenges, as a fundamental tenet of polar travel is moisture management – sweat, once cooled, turns to ice, trapped against the skin by layers of clothing. Progress is slow as we strain up the steep avalanche-prone passes, detouring to cross the mountain faces like a yacht tacking upwind.

Flatter terrain awaits on the other side of the range, but so too does the weather. Gale force winds bring limited visibility and a knifing cold on inadvertently exposed skin as we push through thick powder and whiteout conditions, navigating by compass and the sled tracks of the person in front. The end of the day brings the possibility of a warm meal and shelter, but first we must secure our tents in the blustery conditions. With single-minded concentration, each team focuses on the task – the tent is the lifeline for survival in these conditions. In Greenland in 2013, a British team suffered a tent failure during 150 km/h winds a day into their expedition – one man died and the remainder were evacuated with frostbite and hypothermia.

With three to a tent, there is not much room for the evening and morning routines of cooking, repairs and preparation. By the light of headlamps we eat a variety of dehydrated meals, the packaging removed to save weight – a lucky dip as to what nourishment will help to offset the nearly 6,000 calories being burned pulling the sleds for 8 hours a day. It is not long after sunset that we will collapse into our down sleeping bags, and sleep until dawn, when the small crystals of ice that line the tent roof from our warm breath start to melt and drip onto our faces.

The routine continues each day. Ski for eight hours, eat and rest for eight hours, sleep for eight hours. It gets boring, and polar explorers report this as the hardest challenge – not the cold, crevasses, starvation, blisters or loneliness, but the endless monotony of walking across a blank landscape for days and days, with only your thoughts and “the little whiny voice in your head that tells you to stop”, as explorer Sir Ranulph Fiennes describes it.

The trick is to take one day at a time – if that is unbearable, then one hour at a time. Or when even that seems impossible, one minute at a time. So we ski, eat and sleep. Then we do it again, and again, until one evening as the sun sets behind the range, the lights of Finse dot the horizon in a gentle glow, and we drop back down into the village.

We have covered 200 km in ten arduous days. The next journey will take us months across the harshest desert in the world, in the coldest place on Earth. “Do we have what it takes?”, asks the voice in our heads. There is no answer – just ski, eat and sleep. And repeat.

Jack and Kelly are members of The Spirit Lives Expedition, an Australian and New Zealand team undertaking a coast-to-coast crossing of Antarctica in 2021. To learn more, go to thespiritlivesantarctica.com.