a poetic tribute to

freda du faur

An account in verse of the first female ascent of Aoraki/Mount Cook by Emmeline ‘Freda’ Du Faur in 1910.

Words by Dan Slater

(An earlier version of this poem featured in Wild #180, Winter 2021)

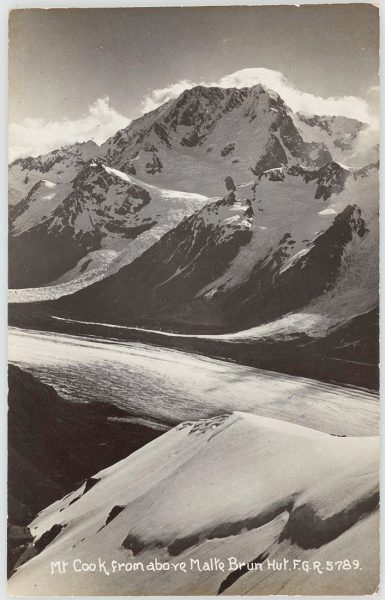

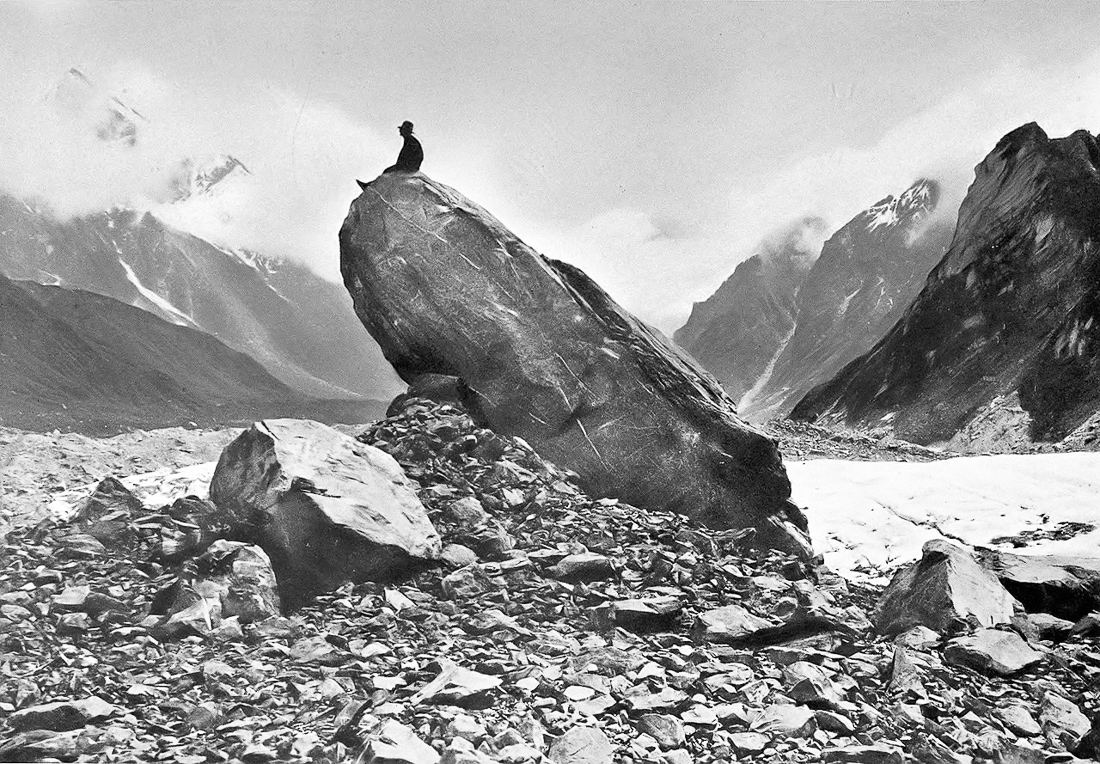

Born in 1882 to wealthy parents, Freda Du Faur grew up in Ku-ring-gai, Sydney. There she learned the basics of rock scrambling, but it was her first family visit to the mountains of New Zealand that really set her heart alight. She persuaded her father to allow her to visit The Hermitage, a popular resort hut below Aoraki/Mt Cook, where she was enthralled by the beauty of her surroundings.

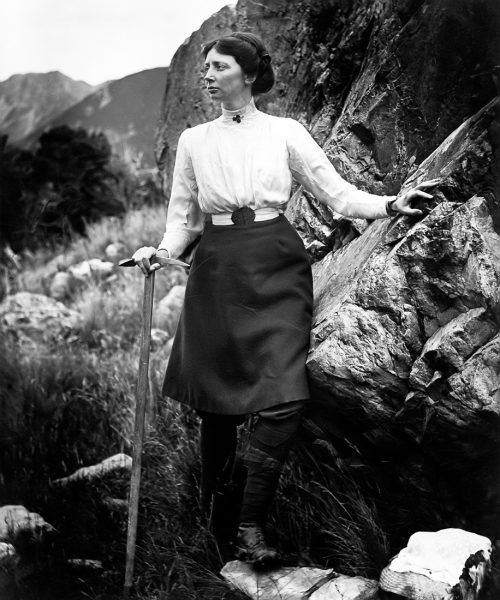

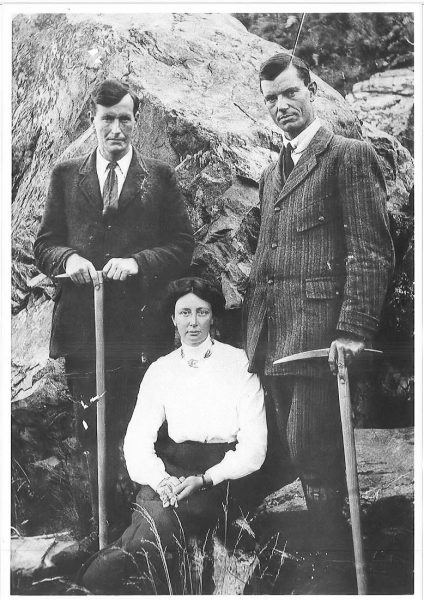

Returning the next year, determined to try her hand at mountaineering, she hired renowned guide Peter Graham. Her daring attire and unwillingness to hire a non-climbing chaperone brought gossip from the society ladies, but she was unfazed, and her natural ability and unbridled enthusiasm shone through.

In a time when most women were trapped in domestic roles, Freda was an example of freedom and an inspiration to many. Her talents combined to propel her to ever more impressive feats of mountaineering, and in 1910 she became the first woman to summit Aoraki/Mt Cook. With Peter and his brother Alex as guides, they broke the existing speed record.

Many more summits followed over the next few years, but tragically, events then took her away from New Zealand and she never managed to return. She’d fallen in love with fellow Sydneysider Muriel Cadogan, whom she met while training for Mt Cook, and they lived happily for a while in Europe, from where in 1915 Freda published a book detailing her time in the Southern Alps—The Conquest of Mt Cook and other Climbs. Muriel’s family disapproved of their relationship and had her committed to an asylum, back then a terrible yet somehow acceptable punishment for homosexuality. Virtually imprisoned, Muriel wasted away, mentally and physically, and eventually died, aged 44.

Freda never recovered from the loss, living alone in Dee Why before ending her own life in 1935. She was buried in Manly Cemetery, Sydney, in an unmarked grave. It was not until 2006 that a plaque was erected at the site by a group of New Zealanders including Sally Irwin, the author of du Faur’s biography, Between Heaven and Earth.

A Snow-Starved Australian Soul

“Mistress du Faur,” came the alarum, “If you’d be so kind,

To rise for breakfast when you’re so disposed.”

As Freda stirred from restless sleep, foreboding gripped her mind,

She bent her will to keeping nerves composed.

She crawled from under blankets warm, excitement catching breath,

And stared up at the mountain, raw and bleak.

Aoraki loomed above their perch, her buttress off’ring death,

To those who sought to stand atop her peak.

From canvas strung o’er two ice poles was fashioned humble bed,

From which they would their objective attack.

She drew her hobnailed leather boots from pillowing her head,

As tang of meths pervaded bivouac.

The moonless sky was crisp and cold with not a cloud in sight,

As team devoured fruit and sucked down tea.

They greased their faces ‘gainst the chill and wound their puttees tight,

Their candles hoisted high so all could see.

Six footsteps crunched on hard-packed snow as they began to climb,

Our lady flanked by hardy Graham boys.

With Peter fore, and Alex aft, they made outstanding time.

Engrossed in one of life’s unbridled joys.

Her first glimpse of the Southern Alps was day that changed her life,

And fixed her mind at once upon a goal:

She’d wed the mountains there and then, disdaining fate of wife,

To true fulfil her snow-starved ‘stra-lian soul.

These four years since, of nothing else but summit had she dreamt,

Last season’s failure bitter to recall.

Cloud Piercer had on that occasion foiled her first attempt.

With mighty bergschrund rearing deadly tall.

That morn she’d left with elder Graham, bent on climbing two,

While pressure glass was dropping like a stone.

“Against all mountaineering rules!” Jack Clark’s words at them flew,

And truth – they’d soon regret they were alone.

The game was worth the candle yet, the two of them agreed.

They fretted not what Clark and comp’ny thought.

‘Til barricade of rock and ice compelled them to concede,

Alas, combined exertions came to naught.

Thus bitter disappointment for the lady Emmeline,

Afeared she was that she would lose the race

To skilful European frau with concentration keen,

Who’d quick before her stand in hallowed place.

But twelve months later none had shown and folk were placing bets.

Determined Freda vowed she wouldn’t fail.

Now veteran of Sefton, Malte Brun and Minarets,

Mt. Sealy and evocative Nun’s Veil.

Her hopes would not be dashed this time by lacking strength enough.

At Dupain Institute she trained all year,

And hired the younger Graham lad, reserved yet quietly tough.

Ne’er ‘gain would dearth of numbers cost her dear.

Harsh criticism came instead from prudish end of scale,

Of single lady lacking chaperone.

To sleep with guides in single tent was quite beyond the pale.

Best morals keep, and freeze to death alone.

“If reputation is so frail, it will not pass that test,

I’m happy to be rid of useless thing.

Perhaps appendage I should seek, the female climber’s best:

A strapping husband alpinist to bring.”*

Which brings us back to 1910, that chill December night,

The boys wore tweeds complete with knotted ties.

In knee-length skirt and knicker-bocks, our girl was quite the sight,

That ne’er before met mountaineer’s eyes.

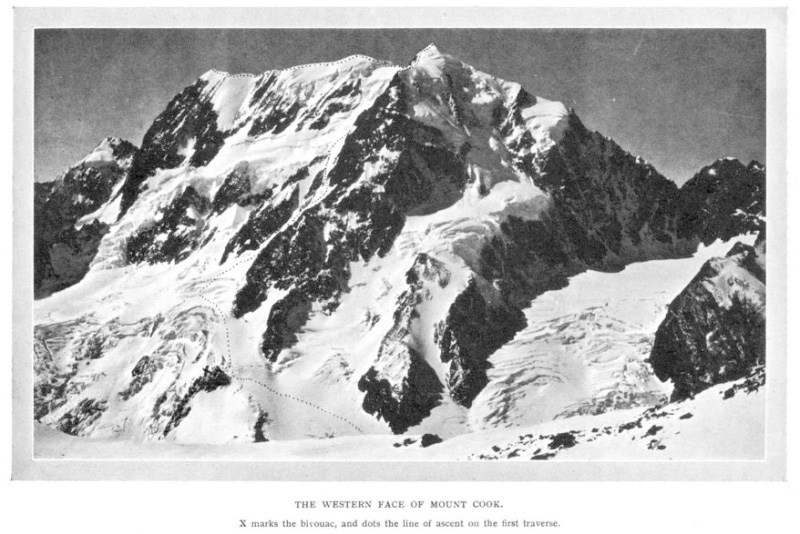

By 4am the candles snuffed and stashed in Haversacks.

Manila hemp rope wound around each breast.

They plugged uphill at quite a clip, the bergschrund at their backs,

To pause beneath a Buttress facing West.

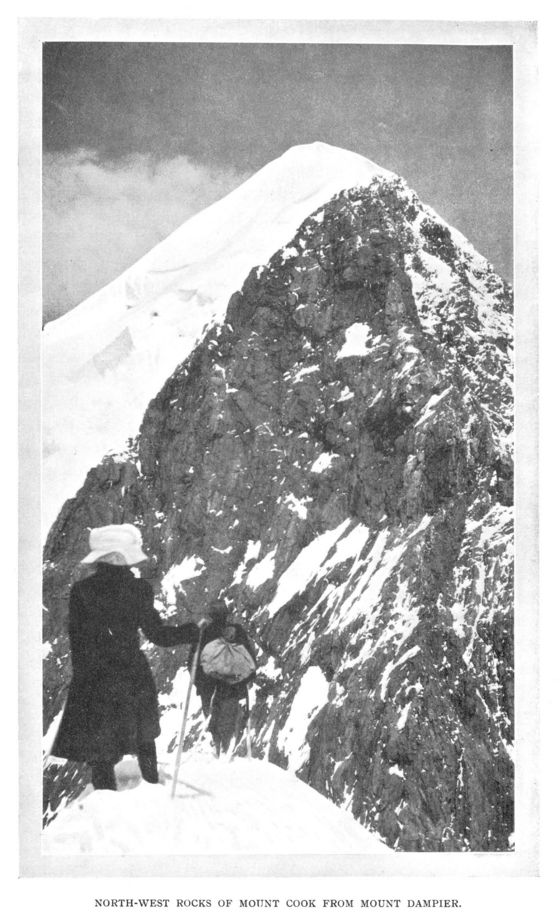

The route they took was recent forged by climber Laurence Earle,

Accomp’nied by Jack Clark and Graham guides.

Could repetition come so soon, by this ‘a mere girl’?

She aimed to do just that and more besides.

The Earle Route led off solid rock and onto rotten shale,

Scarce held intact by treacherous blue ice,

Where one by one they inched across, the handholds faint as Braille,

With rock fall hazard left to roll of dice.

Despite superior climbing skills obtained while just a pup,

In youthful forays ‘round Ku-Ring-Gai chase,

Her critics oft’ accused du Faur of being ‘carried up’,

A slander aimed to keep her in her place.

The aneroid now measured yet one thousand feet to climb.

With skies still clear, young Freda dared to hope.

Their pace was good, they still felt fit, they double-checked the time.

The summit record hung upon a rope.

But many barriers remained to nudge their win to loss.

First up – a frozen film of smooth green glass.

Impossible to find a hold, they only scratched across

By leaving swathes of skin stuck to it fast.

Beyond that trap a couloir lay, its neck a clean white chute,

Yet pummelled by the keen wind rushing down.

Dry-mouthed they pushed their bodies through, ‘til finally the route

Arrived beneath the summit’s churlish frown.

While Peter chopped the final steps, chips flying from his axe,

Our hero’s mind was harking back to home,

And new found friend Miss Muriel Cadogan, in whose tracks

The future lay. Together they would roam

Along life’s steep and rutted paths, beset by prejudice.

’Cross continents and decades their love spanned.

To madness, grief and suicide from early years of bliss.

Whatever came, they met it hand in hand.

Such tragedy was yet to come as Freda climbed the slope,

Her gallant guides already stepped aside,

To let her top out on her own, ahead by length of rope,

First female to complete this rocky ride.

She felt so humble, small and ‘lone, her cheeks inclined to wet,

‘Til joined by friends to celebrate with glee.

And bagging fastest time to boot, of any climbers yet.

Aoraki surely smiled upon these three.

Elated, Freda shook their hands, congratulating feat,

And pulled out trusty 3A Kodak box

To photograph the glorious sight, New Zealand at her feet,

A world comprised of tumbled, icy blocks.

But as she viewed massif below, a new route caught her eye,

One ne’er yet done by woman or by man.

A Grand Traverse of Mt. Cook’s peaks. The time was surely nigh?

In Emm’line’s mind there slowly formed a plan…

Three years later, in 1913, Freda and Peter, along with another guide David Thomson, made the first successful traverse of Mt. Cook’s three peaks. It remains a classic to this day.

*Adapted from a passage in Freda’s 1915 autobiography – The Conquest of Mt. Cook and Other Climbs.