BOOK REVIEW

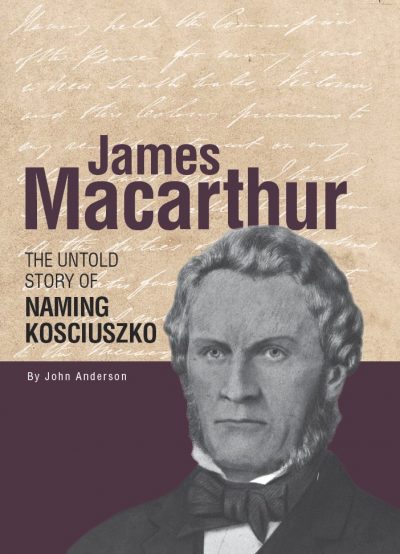

James Macarthur—

The Untold Story of Naming Kosciuszko

Review by Julian Ledger

Just how was it that a Polish resistance hero gave his name to Australia’s highest peak? Who accompanied Count Strzelecki almost to the summit when he made the first recorded ascent of Mt Kosciuszko in March 1840? How did the expedition come about? And how, may anyone who has been there ask, did they find their way up Hannels Spur, that 1700m climb on the west face of the Main Range?

The answer to these questions and more can be found in a new book by Sydney bushwalker John Anderson that was twelve years in the making and the result of granular research: James Macarthur—The Untold Story of Naming Kosciuszko.

James Macarthur (not to be confused with his cousin John) was a pastoralist interested in new land for grazing sheep. It was he who helped provide the means which enabled the gentleman explorer from Poland to tackle the climb. Macarthur also wrote up the more accurate of the notes of the ascent and which are extensively quoted in the text.

John Anderson is well placed to have completed this book. His career took him to road building projects north and west of the Snowy Mountains and he has made extensive visits in all seasons. He has been a member of and volunteer for the Kosciuszko Huts Association for 45 years and to this day volunteers with National Parks. As a rogainer and orienteer his love of maps is displayed in the book’s clear cartography by the author along with illustrations including many historic and contemporary photos.

The book carefully sets the context of how far exploration had progressed by the 1830s (Yass was the boundary of the settled district), and the conditions of the roads such as they were. It then details how the party made their way south via today’s Tumbarumba to reach the Murray River and then turned upstream, assisted by a local Aboriginal guide called Jacky, who was familiar with the route to the high country for the annual feast of Bogong moths.

The author has climbed Hannels Spur three times, the last time in a marathon effort all the way from Geehi to Thredbo in one long day and being before the track was re-cleared. Hannels Spur had become overgrown after the 2003 bushfires and was in danger of being lost to walkers. At the time, almost everyone ascending Kosciuszko was doing so via easier routes—such as from the road head at Charlottes Pass or the Crackenback chairlift from Thredbo—than the original route. In 2017/18 Wild celebrated the story of the weeks-long project by National Parks aided by volunteers to recut the Hannels Spur track.

The book’s accounts of the ascents of the mountains of the Australian Alps carry a special aura. There is the question of route choice, venturing into the unknown, logistics, the make-up and performance of the party, navigation, where to camp with water, the summit often being obscured by lesser peaks, conditions experienced including the weather and if, indeed, the climb was even possible.

Notably, Anderson also addresses vexatious and long-running question of which peak was actually climbed first and how they worked out which peak was the highest, a source of debate for many years. Anderson goes into great detail here before arriving at his conclusion (I won’t spoil the book by giving the game away here), but suffice to say, he displays his skills as a historian, experienced bushwalker and analyst to take the reader carefully through this significant journey.

The book is a labour of love, a high quality and engaging publication which above all makes you want to go back to the Snowies as soon as possible.

It’s available from tabletoppressbooks.com