WALKING ON COUNTRY

What are the challenges facing Aboriginal-owned-and-operated guided walking companies? Caro Ryan heads to lutruwita/Tasmania’s wukalina Walk looking for answers.

Words & Photography Caro Ryan (unless otherwise credited)

(This story originally featured in Wild #182, Summer 2021)

Imagine what would happen if the internet disappeared. Without warning, the place we go to research, learn, connect, understand, ask questions and discover—all gone. No more searching for the best knots to tighten a tarp, shave three grams off your pack weight or find a pattern for DIY gaiters. No more places to go searching for the best recipe for dehydrated chilli con carne, to research the Franklin Dam or Pedder protests, to track down the passes of Narrowneck or the history of Myles Dunphy.

How much more precious this knowledge now is, that we see how access can disappear in an instant. How much more revered are the holders of this wisdom. How treasured and privileged it would be to now sit with these clever ones and to hear from them.

This is how it felt to walk, early on a March morning, into the Elders Council of Tasmania Aboriginal Corporation located in a quiet suburban street on the hilly part of Launceston. With the architecture of a community hall and the quiet reverence of a Quaker meeting, the air vibrated with the weight of knowledge, held in the gaze of the surrounding portraits. Row upon row of eyes looked into my soul from their regal assuredness. Humble and quiet, mighty and proud.

The essence of the history of the palawa nation hangs heavy in this space. The knowledge of all things lutruwita/Tasmania is an invisible fog that inhabits this place. To learn how and where to live, how to build and tear down, to become a man, a woman, a mother, father, teacher, hunter, fisher, healer—all that has come before—is not written down, not in books to pass along nor a web page that springs from a keyword. This knowledge comes from listening at the right time and in the right place.

This is the weight of the Elders.

I’m here because I read a 2019 article by Bob Brown in the Guardian. It ends with his words, “Returning home, I post Carleeta a shiny pink-shell palawa necklace I had purchased from a Hobart gallery years ago. It belongs to her.”

As I craned my neck to look up into the eyes of the black and white portrait photos of Elders, I didn’t know that three days later, I’d hold that necklace in my hand.

This is the start of the four-day, three-night, wukalina Walk, an Aboriginal-owned-and-operated journey up and beyond wukalina/Mt William in the northeastern tip of Tasmania.

I’m here loaded with questions. Questions for my hosts and for my guides, questions to myself, questions of commercial walking tour operators and the industry they drive, and questions about post-invasion politics and society.

Sparked by earlier research looking for tour opportunities to walk multi-day on Country with local Aboriginal guides, I knew there weren’t many owned and operated by communities or Aboriginal businesses. I found just four: two in Western Australia (Lurujarri Heritage Trail—a community walk in Broome, and Black Tracks—a tour business in the Kimberley), one in the NT (Larapinta Culture from Alice Springs), and one here, in Tasmania where I find myself now.

What I wanted to know was why. Why at a time of huge interest in guided walks across Australia, where every step we take is on someone’s Country, are the companies owned by whitefellas, with profits, sway, confidence and capacity building, coming back to whitefellas?

And so, looking for answers, I found myself in Launceston at the Elders Council of Tasmania Aboriginal Corporation, being welcomed by Uncle Clyde Mansell—a force of nature whose relentless work enabled his vision of the wukalina Walk to become a reality—about to embark on the last tour for the short walking season which runs from September to March.

Over four days, I walked, sat, and listened as guides Hank, Carleeta and Ash generously answered my question of ‘why’. Their answers pointed to my own ignorance and lack of understanding of Australia’s First Nations’ journeys, with challenges that go deep and broad, forming a checklist of obstacles of which even half would deter any startup. Issues with capital (both financial and experiential), capacity, historical trauma, confidence, scrutiny … they all individually create obstacles, but when added together, they form an almost insurmountable barrier.

“The interpretation that Hank, Carleeta and Ash share hasn’t come from books. Their knowledge, instead, comes from listening and being. It comes from their Elders.”

So while the wukalina Walk’s slick branding and professional PR might look right at home beside the big players in the Tassie walking market like Tasmanian Walking Company, Walk Into Luxury or Life’s an Adventure, peel back this outer shell and you’ll find something fundamentally different.

“We’re not in this to build big profits,” says Guide Hank Horton. “We’re here to build community. It’s about creating a business that the Aboriginal community can be involved in, can be employed with and have a say in how that’s run.”

Hank tells me this at the Aboriginal Elders Council Centre over tea, scones and muttonbirds. The muttonbirding season on truwana/Cape Barren Island runs from the end of March to the end of April, and it’s central to community and connection here.

“To see Aboriginal people on a muttonbird island is to see people in their true element,” says Uncle Clyde Mansell.

“[F]or a short period of five weeks, we are in control of our cultural destiny.” This control of cultural destiny, self-determination, capacity-building and commercially sustainable model is what I’ve come to Tasmania see.

There are other companies that run guided walking trips in and along the Bay of Fires. But while they’re operating in the same national park, on the same stretch of coastline, following roughly the same route, they’re completely different animals. The interpretation that Hank, Carleeta and Ash share hasn’t come from books. And while Hank and Carleeta have both completed the respected Cert III Tour Guide’s course at TasTAFE, they didn’t get it there either. Their knowledge, instead, comes from listening and being. It comes from their Elders.

Developing any idea into a viable business or tourism product takes money, time and skill. It’s not surprising, therefore, that lack of access to capital is a major obstacle for an Aboriginal-owned-and-run startup. In wukalina’s case, the journey was kicked off with philanthropic funding and good relationships with some influential Tasmanian business owners, who shared Uncle Clyde Mansell’s enthusiasm and could see the potential. Once the wheels were in motion, with interest from the private sector, Mansell was able to leverage government funding as momentum built.

But capital is not just financial. There’s intellectual and experiential capital, too, and the fact that wukalina had no competitors created a barrier that would surprise many people. Usually, a ‘gap in the market’ like this makes entrepreneurs froth. But it also means there’s no established knowledge of that market to draw upon; establishing a new genre, and way-finding a whole new route through an unknown landscape, is hard. It takes vision, foresight, and mental and physical resilience. And think about having the skill set to write submissions. Submissions are difficult for industry insiders, let alone for many remote Aboriginal communities with no experience in the field. How do they even start? And if they want to pay a consultant to do it for them, where do they get the funds?

And where do they get the experience? For Carleeta—who was the last baby to be born on truwana/Cape Barren Island—that meant working hard to get through her guiding qualification in Hobart. “I didn’t think I was going to pass, but as soon as I had the opportunity to design a one-hour tour, bring my TAFE group out and walk up to the summit, talking about the islands and connection to Country, that’s when they said, I passed the course.”

This training-on-Country concept led the community to support Hank through his Cert IV Trainer and Assessor’s course, with the aim to offer local community members the opportunity for a recognised qualification in guiding. The key difference being that it’s not taught by a whitefella, in a whitefella classroom, in a city 200km from home.

For all that training and knowledge, however, the financial rewards are uncertain. Every hiking guide in Australia knows the pay and conditions of an industry that relies on its casual workforce is not great. Most choose guiding as a lifestyle for a few years, instead of a long-term career. The common tale of guides leaving the industry after marriage and a mortgage holds true for wukalina, too, where one former guide made the hard decision to take consistent, higher wages at Woolworths.

But while travelling with the guiding seasons—summer in Tassie, winter in Central Australia—can provide non-Aboriginal guides with year-round employment and greater financial rewards, that’s not the case with wukalina. The stories of this place can’t travel. For Aboriginal guides, mobility is well-nigh impossible. Relatedly, it also makes it more difficult for Aboriginal tourism operators to recruit guides. If story belongs to place and people, the capacity of storytellers isn’t something that can easily be built by enlisting outsiders.

“I’m so proud of these young ones coming forward,” says Hank, referring to Carleeta and Ash, “but there are only four of us, week after week, it is hard. We have to build the capacity of our guides.”

“[W]e are now a glowing example to the broader community, to show that these blackfellas can do this and are quite capable of running a business and managing their Country.”

Scones, stories and gear checks at the Elders’ centre complete, our small group of nine walkers load onto a Coaster bus and head north along the Tamar River, before turning east towards Bridport.

Crossing Pipers River, something changes in Hank as his sharp-minded, big-picture history lesson of Tasmania slows and his shoulders relax. He’s just told us the importance of landforms as boundaries. Here, we’ve crossed into Hank’s Country. “A lot of people would feel unsafe being out here, stuck out in the wilderness. We feel safe because it’s home. It’s like opening the backdoor and walking into your home.”

By crossing the river with Hank, it feels like we’ve come in through the familiar swing of a backdoor, to feel welcomed and safe. “It is more of a journey than a tour,” Carleeta explains. “We want our guests to feel that they are a part of our family and community. We don’t do a regimented thing or any forced marches. Our interps will come quite often from our stories or our connection with Country, or animal.”

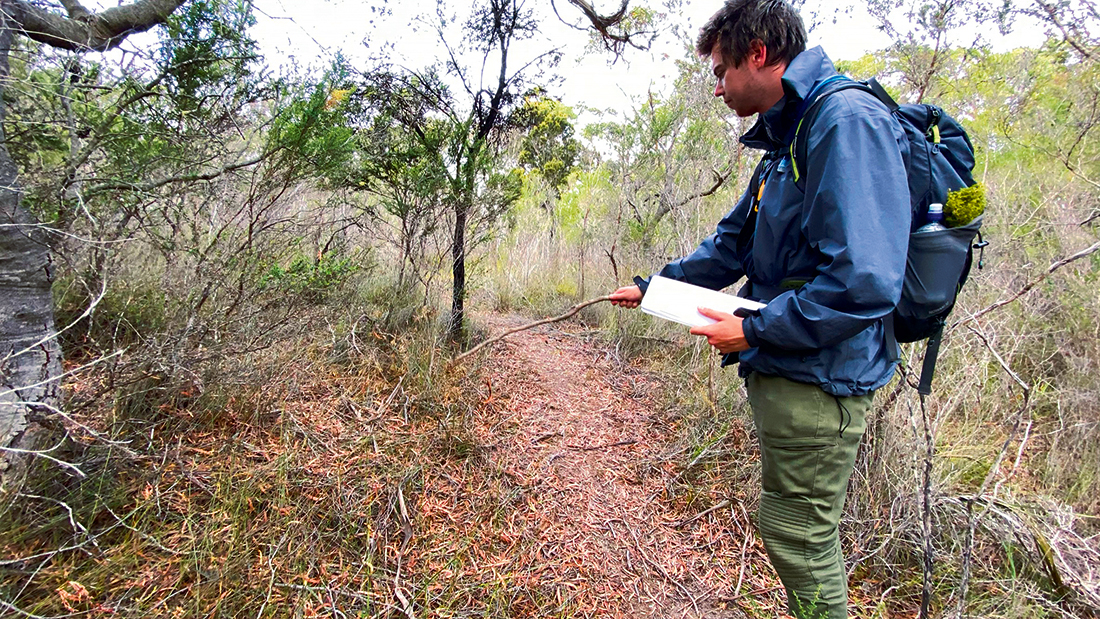

That gentle, connected approach informs the pace that we walk at and is dictated by the thoughtful and respectful, ‘spider waltz’, that young guide in training, Ash, performs at the head. With a stick in hand, he mindfully and calmly moves the spider webs from across the tunnel of track that leads us through the melaleuca scrub.

“When we’re getting bush foods, it’s not just about picking that plant or taking that animal, there’s a spiritual connection to that.”

Like places all around Australia, the story of Tasmania’s Aboriginal people post-invasion is a traumatic one. It’s a trauma that wukalina guides—as do all Aboriginal guides—re-live week after week in doing their jobs. To tell their stories, without the filter of making it anything other than what it was, adds a layer of complexity, and the added burden weighs more on their shoulders than the weight of any 90L guide’s backpack ever could.

“It’s emotional for us, a lot of the stories we talk about are dredging up memories for us. We get emotional and we cry and it’s mentally draining as much as it is physically draining on us.” Hank explains.

This history isn’t necessarily 200 years old either. It was as recently as 1975 that some of Hank’s cousins were stolen, removed as part of the planned disbursement of palawa’s stolen generation.

This history has inertia. It also directly impacts confidence. “[There is] self-doubting,” Hank says, “because they’ve been told for bloody years that we’re dumb blackfellas that can’t do anything. That does rub off.” And while public speaking in general takes guts, it’s especially the case for Aboriginal guides; many potential guides are fearful of sharing their stories and opening themselves up to criticism.

Mind you, it’s hard to see a trace of the shyness and lack of self-confidence Carleeta says she had before joining the wukalina team. We’re on Day Two of the wukalina journey, and it’s Carleeta’s time to shine. She leads our group along the beach to a significant ‘Cultural Living Site’, explaining that the term midden is Gaelic for rubbish heap. “I never used to talk in front of people,” Carleeta tells me later. “I had a stutter up until I was about 16. Once you feel comfortable and know what you’re talking about, you definitely become more confident in yourself. Since doing this, I’ve been able to become more grounded and centred.” Carleeta hopes to mentor other young guides. It wouldn’t surprise me if in years to come she is known as Aunty Carleeta.

The more the east coast air fills my lungs, the more I share community-cooked meals around the communal table, the more I realise there’s another lurking answer to the question I came here with. Running a tourism business anywhere is hard. Running an Aboriginal tourism business is even harder. But the layers of extra complexity and challenge stretch beyond the logistics of people and place to include levels of scrutiny from government and industry that appear above those directed at non-Aboriginal enterprises.“We make one little mistake,” says Hank, “and the whole of the government and community would be over us like a ton of bricks.”

It doesn’t help that some of the solutions offered by traditional tourism and government power brokers are not solutions at all. Opinions such as ‘Why don’t you just sell to Tas Walking Company?’ show their cards in a way best summed up by Hank: “Whitefellas see Country as what value they can get out of it; we see it as our survival.”

“It took Uncle Clyde 15 years and three Tasmanian premiers to get it through. He was a dog with a bone. … His thinking was if we can show the government that if you give us back the right parcel of land, we can turn it into a community business or community experience. … We are now a glowing example to the broader community, to show that these blackfellas can do this and are quite capable of running a business and managing their Country.”

Well-hidden among the sand dunes, boulders and coastal scrub of banksia and grass trees is krakani lumi (resting place). These award-winning structures provide shelter in the truest sense of the word, with their timber domes reaching around you, to embrace and welcome you. But until you round a large banksia and are standing in front of them, you have no clue how far you are from the goal for the day—you just keep walking through the scrub to a secluded, beautiful, resting place. This mystery of the unseen goal feels akin to the future of Aboriginal owned tourism in Australia. Hidden, beautiful, surprising, sustainable and completely at home.

“Our community,” says Hank “is confident that we’re doing a sensible business activity on our Country, but we do it in a very spiritual and respectful way.”

But with many community groups seeing the impacts of mass tourism at Uluru and Kakadu and an understanding of the challenges involved, there’s a wise reluctance to jump on the tour bus bandwagon.

Hank, however, is optimistic, “I’ve been talking to the old fellas over at Kakadu way and they’re using us as an example up there. They’re saying, ‘look what all those young mobs are doing down there in Tassie?’ It’s pretty good when they use us as an example, because we’ve been using them as an example for years.”

Learning is what wukalina is all about. Sitting in a circle, Carleeta teaches us about shell jewellery and hands us a standout example of a traditional shell necklace, pearlescent and radiant. The weight of the piece (the returned artefact Bob Brown gave to Carleeta) reflects the precious gift that these four days have been.

CONTRIBUTOR: Caro Ryan is the author of How to Navigate—The Art of Traditional Map and Compass Navigation in an Australian Context and teaches navigation in the Blue Mountains, NSW.