Olegas Truchanas was a Lithuanian born Tasmanian wilderness explorer and photographer. Olegas was one of the first Europeans to explore deep into Tasmania’s South-West region. His solo journeys and the stories and photos from these explorations have become part of Tasmanian folk history.

Olegas in Kayak – Truchanas Family Collection

Olegas grew up in Lithuania in the 1930s, and was no stranger to hardship, having fought with the Lithuanian Resistance Movement during World War II. When the USSR occupied Lithuania after the war, he was one thousands of youths who left the country, migrating to Germany where he studied Law and the University of Munich. While Olegas always intended to return to his motherland, this never eventuated and in 1948 he migrated to Tasmania.

Like many before him, he sought solace in nature and found himself venturing deeper and deeper into the unexplored wilderness of the South-West.

In 1954, Olegas attempted an audacious trip, to paddle northwest from Lake Pedder to Macquarie Harbour. Using a specially built canvas kayak, Olegas would follow the course of the Serpentine-Gordon Rivers, out to the west coast of Tasmania.

Lake Pedder from Frankland Range – David Neilson

The original Lake Pedder had a wide and open quartzite beach on which light aircraft could land. Olegas was flown in with all of his gear, including about three weeks of rations, and the kayak, which he had designed and built himself. Travelling across the Lake and the upper Serpentine River went according to plan, but he then ran into trouble.

During the descent into the steep Serpentine Gorge, just before the Serpentine’s confluence with the Gordon River, torrential rain and rising waters made his craft difficult to manage. He got washed over a waterfall. He lost his kayak and most of his gear with it, including his pants. He saved one bag that contained his sleeping bag, tent, camera and his book – A.C Garrard’s The Worst Journey in the World. He had to find his way back to Lake Pedder on foot.

With no trousers, Olegas had only his japara jacket to provide any sort of protection. So he stepped through the arms and tied the rest of the jacket around his waist with a piece of string. In this fashion, he trekked back to Lake Pedder – a journey of many days – where he was lucky to find Lloyd Jones with his light aircraft parked on the beach. Olegas was back in Hobart that afternoon.

Surface of Lake Pedder – Graham Wooton

Olegas waited three years before he made his second attempt. He learned from his previous experience and disassembled his kayak for portages through difficult sections. He was also equipped with his new twin blade aluminium paddle which helped him negotiate the rapids. At times he had to dismantle his kayak to climb the canyon walls and shuffle loads– first with pack, then with the kayak. He eventually reached Macquarie Habour, becoming the first person to ever navigate the Serpentine-Gordon Rivers. He presented memorable slides of his journeys to Hobart audiences. With his stories, he awakened love and respect for the rugged beauty of South-West Tasmania, which previously was known only as the ‘empty quarter’. What he didn’t know was that only a few years later, the course of these wild rivers would be altered and Lake Pedder would be transformed to become a water impoundment for a hydro-electric power scheme.

Overcast weather over Lake Pedder – Elspeth Vaughan

In 1964, there was an exploratory road bulldozed into the South-West, as part of the Hydro Electric Commission’s Gordon Power Scheme. A year later, Premier Eric Reece announced plans for the ‘modification’ of Lake Pedder National Park (declared in 1955). Despite public outcries, the Tasmanian government revoked the status of this National Park in 1967, to allow for the hydroelectric development proposed by Tasmania’s Hydro Electric Commission.

Olegas understood the value of what would be lost with flooding Lake Pedder. A beautiful and unique lake was about to disappear. He understood the value of the experience that would be lost to future generations of people. He made plans to show the Tasmanian public what they were about to lose.

With help from a friend, Ralph Hope-Johnstone, Olegas organised audio-visual presentations to be shown at the Hobart Town Hall and other places around Tasmania. The Lake’s beauty and rugged charm captured people’s imagination, and to some it became unthinkable that this splendid beauty could be destroyed in the name of progress.

The movement to prevent the flooding of Lake Pedder gained momentum, and in the early 1970s, thousands of people visited the lake before it was set to disappear. But at this point in Tasmania’s history there was no stopping the HEC and construction of the dams went ahead as planned. In 1972 Lake Pedder’s beach was submerged.

At this stage of his life, Olegas had become an admired conservationist. In addition to this Lake Pedder activism, Olegas also fought to help permanently protect a stand of Huon Pines by the Denison River. In this, he was successful and the Truchanas Huon Pine Forest stands protected to this day. He was often called on to make public presentations where he would share stories of his trips and his photographs. In November, 1971, at the opening of an exhibition themed on Lake Pedder, Olegas delivered a plea for the conservation of the natural world.

“Is there any reason why Tasmania should not be more beautiful on the day we leave it, than on the day we came?… If we can revise our attitudes towards the land under our feet; if we can accept a role of steward and depart from the role of the conqueror, if we can accept that man and nature are inseparable parts of the unified whole, then Tasmania can be a shining beacon in a dull, uniform and largely artificial world.”

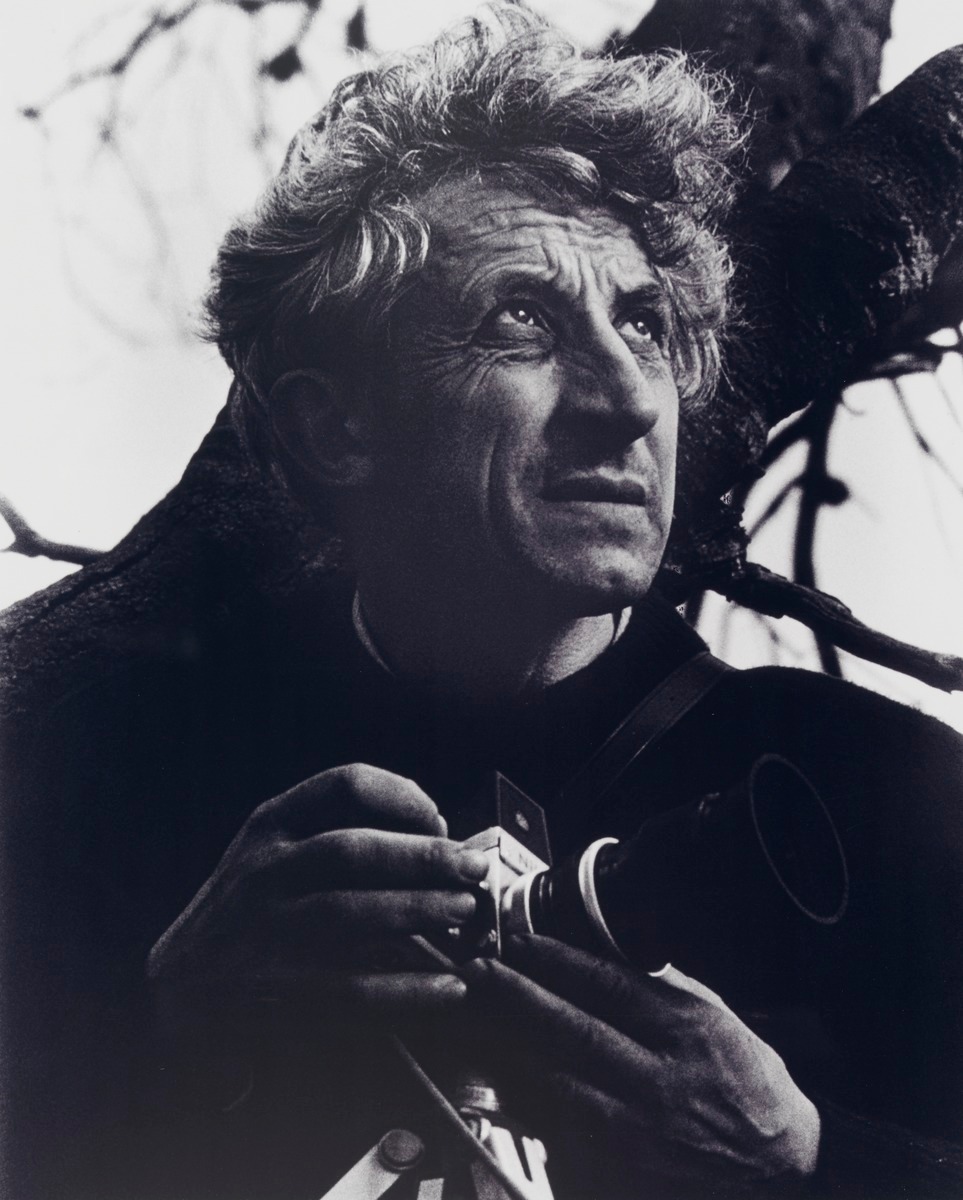

Portrait of Olegas – Ralph Hope-Johnstone

In 1967, Tasmania was scorched by raging bushfires. Olegas and his family lost their home to the fires. Fourteen years of photographic slides was burned to ash.

In 1972 with the HEC’S next phase of the Gordon Power Scheme imminent, Olegas decided to paddle the mighty Gordon River one last time, to recapture the river’s wild beauty before it too, was flooded. This trip would turn out to be Olegas’ last. As he stepped out of his kayak to make a landing he slipped on a rock. He was washed down a waterfall and disappeared. His death was witnessed by a young Kevin Kiernan, who put the call out for a search to commence. Olegas’ body was found later.

Olegas had drowned in the river he sought to save.

Ten years later, a powerful environmental movement inspired by the loss of Lake Pedder prevented a tributary of the Gordon, – the Franklin River – from being flooded.

Written by: Andy Szollosi, Hobart, April 2019

A special thanks to Melva Truchanas for collaborating on this article.