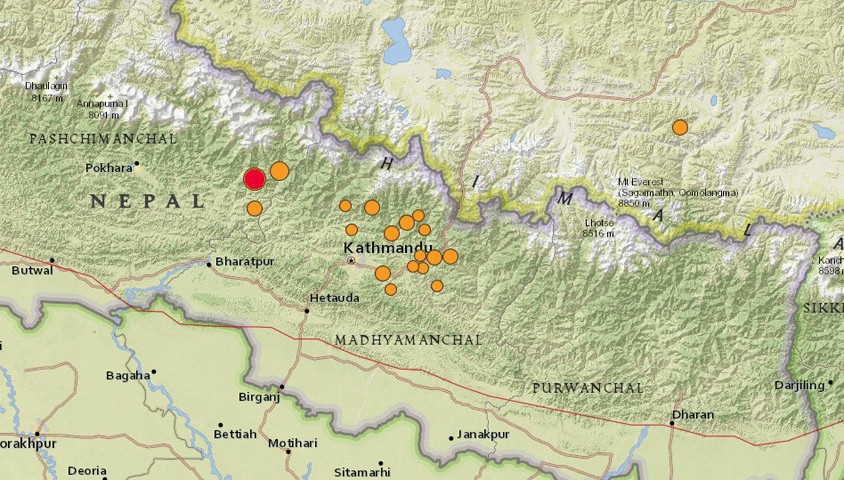

On Saturday, an earthquake occurred less than 100 kilometres northwest of Nepal’s capital, Kathmandu.

Estimated to have occurred at a shallow depth of 10-15 kilometres below the ground and with a magnitude of 7.8, this is the most severe tectonic event in the region since the 2005 Kashmir earthquake, which itself caused over 155,000 casualties and left millions without shelter.

In the days following the event, the world is now beginning to witness the full extent of the havoc this recent Nepalese quake has wrought on locals and visitors alike. While local papers tend to focus on the lives and stories of its own, it’s impossible to overlook the scale of suffering to which the Nepalese people in affected areas are being exposed. As of Sunday, Nepalese authorities have reported 2430 deaths, with 1159 of these occurring in Kathmandu alone. Neighbouring countries have also reported loss of life in the wake of the earthquake.

Now, Australian media has reported the likely death of one Australian climber on Mount Everest, and with hundreds still unaccounted for across the region, it seems likely this figure will rise in days to come.

Climbers on the world’s highest peak were especially vulnerable to the major and subsequent tremors of the earthquake, the impact of which caused avalanches and rock slides that have had a major impact on accessibility beyond their immediate threat to human lives. Reports indicate that many villages and regions may be considered impassable for some days, if not weeks, thereby reducing any rescue attempts to airlift only.

On the face of it, the immediate death toll following the Nepal quake may make this event look less severe than similar global events in the past 10 years. It’s far too easy to compare this event with the horror incurred by the 2010 Haiti earthquake, or the tsunami that swamped the east coast of Japan a year later. Even when compared with the Kashmir earthquake of 2005, the Nepal earthquake appears minor by comparison.

Instead, this event has quickly become a global phenomenon due to the number of foreign nationals frequenting the region at the time. Perhaps the iconic nature of Kathmandu and Everest are enough to place this tragedy in the headlines for weeks, while the loss of Australian lives will keep the media mill churning for many more.

Yet the act of absorbing the news of such an event without having some direct connection to those involved in it*, of experiencing the third-hand horror and in sharing the deeply painful loss of those families touched by the tragedy, can only be understood as some form of macabre voyeurism unless the viewer is moved to take action. What form that action takes is up to the individual, however it’s critical to ensure as much information has informed your viewpoint prior to making any decision.

In video: A survivor has uploaded terrifying footage of an avalanche tearing through Everest Base Camp.

For Your Consideration

- The Himalayas are a region of high tectonic activity – The ongoing formation of the mountain chain itself is indicative of this, as Indian tectonic plates continues to drive itself into the Eurasian plate at a relative rate of four-to-five centimetres per year. Severe tremors, such as the most recent event, don’t occur often but they do arrive with a certain amount of regularity. Similar events in modern times include the 1905 Kangra tremor (magnitude-7.5), then in Bihar in 1934 (8.1) and most recently with the Kashmir quake.

- A changing climate may enhance the severity/frequency of tectonic events – In 2012, Professor Bill McGuire of University College London introduced a book, titled Waking the Giant: How a changing climate triggers earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanoes. His theory was founded in geological research that shows how Earth’s crust is impacted by the weight of ice sheets, and how the removal of those sheets can cause marked reactions in the form of tectonic events. In the past, these changes happened quite quickly, while today humanity has managed to speed the process up drastically. As global ice is reduced, pressure at all the layers of the Earth’s crust is affected, just as the layers of our atmosphere is. Yet, how this may be directly impacting the world’s tectonic activity has not yet been accurately estimated, let alone quantified.

- Nepal’s earthquakes may be predicted – As the BBC reports, the recent earthquake in Nepal was predicted by researchers in findings presented to the Nepal Geological Society two weeks ago. As it turns out, field studies undertaken by Laurent Bollinger and his team from the CEA agency in France indicated that, historically, earthquakes in the region transferred strain in a westerly direction along their associated fault. The researchers had found what is being termed a ‘doublet effect’ whereby an earthquake to the east of Kathmandu would precede a later earthquake to the west, with a period in between of around 80 years. As it happens, the last time an earthquake occurred to the east was in 1934.

At this point I would like to reiterate that this opinion piece has not been written with a specific aim to encourage people to choose to act in one way or another, but rather to consider further options when watching or reading the news as it arrives.

The above information may already be accepted by some readers, while others may view it with skepticism. Either way, considering these concepts is integral to understanding some of the underlying issues that are now facing the people of Nepal, before we even take into account geopolitical concepts such as tourism, the Nepalese economy, trade and so on. In fact, it’s my contention that these physical concerns should be considered first and foremost, before returning to any matter relating to the influences of human society.

Morality and Travel, In Theory

For many Wild readers, Everest and Nepal are often viewed as destinations, challenges and experiences. From the point of view of a publication, this is good and well. As many people would point out, you can’t truly appreciate something without having experienced it.

Yet it seems that the local culture has been increasingly undermined ever since the influx of new breed of explorers seeking ‘enlightenment’ descended on Kathmandu in the 60s and 70s (the hippies had such a profound impact that a local, ancient road – Jhochhen Tole – became renamed ‘Freak Street’ in their honour. At the same time, more and more visitors began arriving to pit themselves against Himalayan peaks. Today, it seems just about anyone can buy their way into an expeditionary group to Everest, regardless of their climbing experience or even basic respect for what should be a pristine wilderness area.

Regardless of the sea of tents that form the base camps at every well known peak, most visitors would recall the supreme volume of human waste (plastic garbage and excrement), that clutters every gully, hollow and gorge. If we’re to consider the value of social concerns such as the tourist dollar, it would seem that – at least on the face of it – the local people have gained little in the past 50 years but for piles of rubbish. After all, the devastation this earthquake has caused is primarily as a result of the rudimentary building materials used throughout Kathmandu, compounded by the fact that Nepal has very little by way of emergency shelters and hospital facilities.

Ultimately, none of these issues are particularly unique to the Himalayas (other than being the mecca for mountaineers). The world over, we see examples of neglected and impoverished peoples regularly exploited for their services, resources and ability to work. Time after time, we see a wellspring of grief and regret, even guilt, and the ensuring slew of calls for charitable donations, fundraising and foreign aid. Yet there’s something more depressingly ironic in the fact that the focus point for many people is Everest itself, a peak that was first climbed over 60 years ago in an expedition that showed the world that humans could overcome any hurdle.

If we’re to ask ourselves the question: ‘Could this humanitarian disaster have been avoided, or at least lessened?’, let’s make sure we’re considering the matter as it stands. Nepal is a nation of nearly 28 million people, but for many Australians the sum total of our knowledge of Nepalese culture is bounded by the term ‘Sherpa’. Perhaps it’s time that we put aside our traditionally European mindset in thinking that mountains are for conquering and instead turn our attention to assisting those that have to eke out a living in their shadow, not just because a massive, global tragedy has occurred.

After all, there could be no Sir Edmund Hillary without Tenzing Norgay.

*This sentence has been updated upon review following reactions to our Facebook page. It should be made clearer – as it is the case – my thoughts and sympathies certainly lie with anyone involved in this catastrophe.