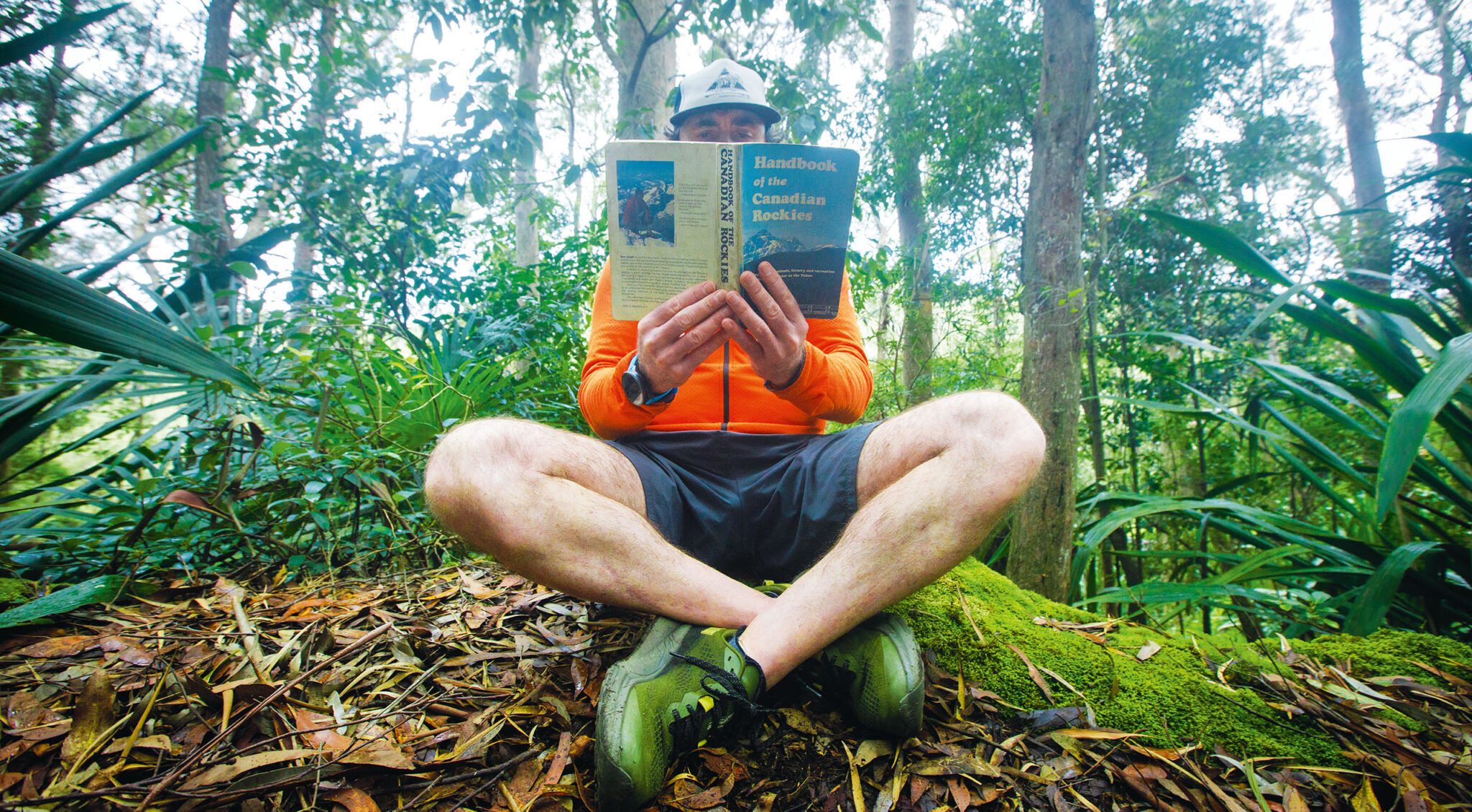

From the Editor: Secrets

Words & Image: James McCormack

(This story originally featured in Wild #183, Autumn 2022)

We all have secrets. According to the Scientific American, this is a bad thing. “It hurts to keep secrets,” it said in a 2019 article called ‘Why the Secrets You Keep Are Hurting You’. It also claimed we have, on average, thirteen secrets, although how they came up with such a precise number seems a little, well, implausible. In any case, I suspect respondents to surveys about secrets tend to keep the number of secrets they have a secret. Or they flat out lie. When I asked my wife what her thirteen secrets were, she not only refused to divulge them, she denied she had anywhere near thirteen secrets. “There’s no way I have that many,” she said (or lied). “Do you?”

“Actually, I do,” I replied. “I have more. Waaay more.”

This isn’t a bad thing. In fact, I wish more people in the outdoors/adventure world kept more secrets. I’m thinking of two things here. Firstly, there are my own secrets, one of which is a discovery I once made of a secret swimming hole, one surrounded by lush forest and cliffs, with a three-channelled waterfall plunging into a dark pool. I tell virtually no-one where this place is. There are also little-known routes that I won’t share widely. Locations of forest valleys with ancient, giant trees. Of secret paths through cliffs and canyons and slots. Of sly backcountry skiing chutes and lines. Because while I’m happy to share most of my knowledge of brilliant natural spots or routes with others, some places, I think, deserve to be kept secret.

Secondly, I am thinking of Instagram, and social media in general. The ABC recently ran a story on the problem of geotagging images taken in Tasmania’s Southwest. Beautiful images are encouraging people into wilderness areas, many of which are fragile, environmentally sensitive locations. And by geotagging, which adds a specific location to the images, copycat photographers no longer have to seek out information and explore areas for themselves; the geotags deliver them right to the spot, with lamentable consequences for hitherto secret spots. The article didn’t come out and say this, but many others do: Instagram is the devil.

“Trying to hold back the flood of information on social media, and the web in general, is like trying to hold back the tide with a bucket.”

Often, I find myself in agreement. But not always, because the problems with saying this are twofold. In fact, threefold. For starters, what can be done about this? Trying to hold back the flood of information on social media, and the web in general, is like trying to hold back the tide with a bucket. We can complain about this as much as we want, but this horse has long bolted. That said, reducing the amount of geotagging seems a sensible and perhaps achievable goal.

But then there is the question of what the fundamental difference is between social/digital and print media here? Or indeed any photography in general. On our Facebook post about the ABC story, one commenter wrote, “I fell in love with Lake Oberon long before social media. It was a Peter Dombrovskis print …”

It’s true; coffee table photo books, guidebooks, and indeed Wild itself, were all encouraging people into these places long before Insta reared its dastardly head. There would be some validity to arguing that complaining about social media is a bit rich coming from the editor of a magazine long devoted to encouraging and inspiring people to go to wild places, and, in the process, sometimes giving away secrets.

In general, however, I believe Wild’s sharing of natural locations has been positive. But not always; there have been mistakes. Even in our last issue, I believe we didn’t do enough to stress the impacts of phytophthora dieback in Fitzgerald River NP (see the Letters page). Most famously, though, there was Wild’s controversial story a little over twenty years ago on the quest for the Wollemi pine. I almost always find myself nodding in furious agreement when I dig into the magazine’s archives to read old editorials from Chris Baxter (Wild’s founding editor, at the helm for more than two decades); his editorial justifying the decision to run the Wollemi pine story was one of the very rare occasions I did not.

“There is no clear-cut point at which the answer to the following question slips from yea to nay: Are the pros of widely sharing the details of beautiful places that inspire us to visit and/or protect them outweighed by the cons of damage by increased visitation?”

Getting the balance right isn’t easy, however. I have knocked back stories pitched to Wild because they revealed too much about sensitive areas. I’ve also, at times, used obscure image captions, or sometimes none at all, if it seemed appropriate. Nonetheless, I’m sure there’d be some who complain that I, as editor, don’t go far enough. That Wild says too much. That it should never reveal anywhere ‘new’.

But there’s a fundamental tension here, one that can’t ever be entirely resolved, and it involves the third problem with completely demonising social media. Because while I will argue for keeping some places secret, there’s no doubt that doing the opposite has led to not only the joy of others visiting those locations, it’s led to some of our greatest environmental campaign successes. Back to Dombrovskis, his iconic Rock Island Bend photo helped sway a nation to fight to protect the Franklin. Who’s to say this new slew of social media images won’t do the same for a younger generation?

And so we must pick and choose. This is not to deny that Insta-fame has no costs: the possibility of erosion, introduced weeds, plant diseases and loss of solitude. I guess the point I’m trying to make here is that this issue of secrets—whether or not to share them, whether or not to widely publicise special, wild places—requires that most precious and often elusive of qualities: Judgement. And the difficulty with judgement is that it doesn’t come with hard and fast rules. There is no clear-cut point at which the answer to the following question slips from yea to nay: Are the pros of widely sharing the details of beautiful places that inspire us to visit and/or protect them outweighed by the cons of damage by increased visitation? But even if our responses differ, we still need to ask ourselves precisely that question. So share when it helps. Keep secrets when it doesn’t. Use your judgement. And above all, tread lightly.

If you liked this piece, you should subscribe to the print mag. Only a fraction of the great stories we run in the mag make it to our website; if you want to read them, head to subscribe.wild.com.au.