Restore Pedder Now

“Is there any reason why Tasmania should not be more beautiful on the day we leave it, than on the day we came?”

Words: Bob Brown, Christine Milne & Tabatha Badger

Header image courtesy of B Hynes

(This story originally featured in Wild #183, Autumn 2022)

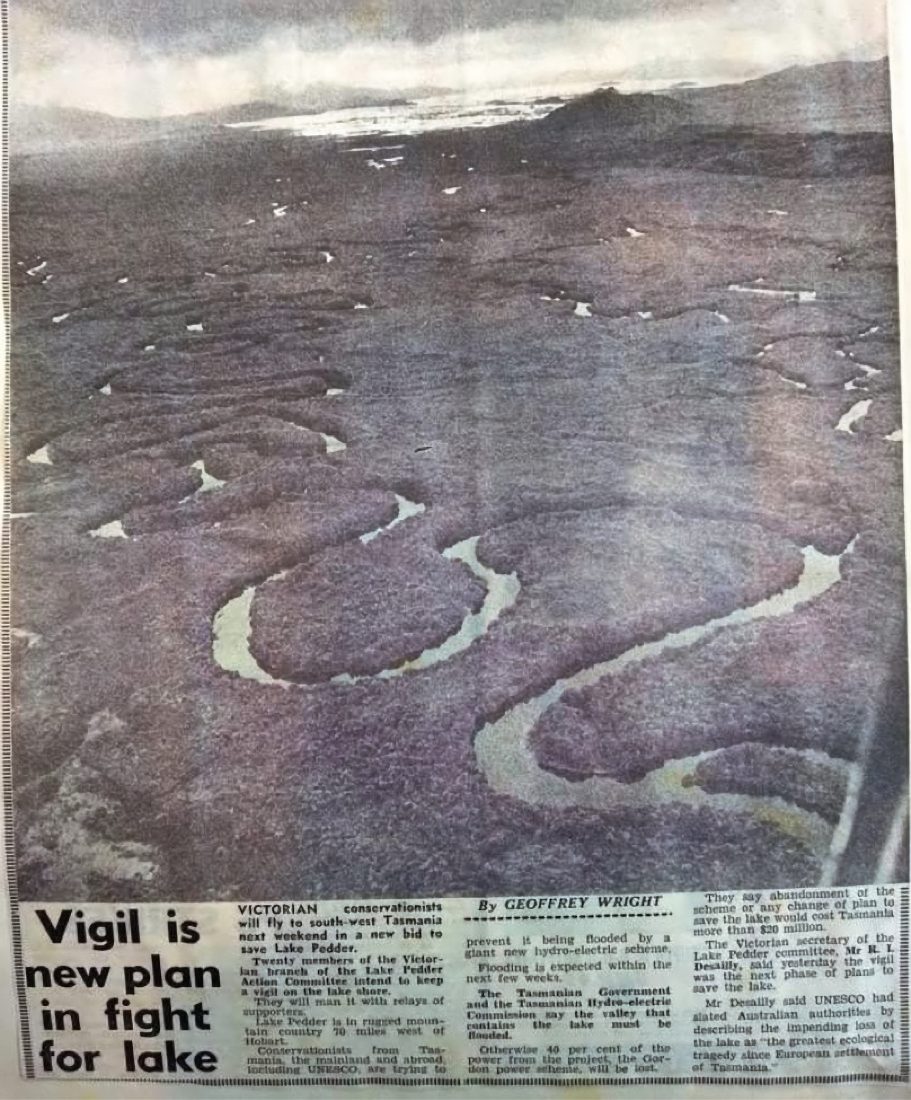

2022 marks the fiftieth anniversary of the tragic and shameful flooding of Southwest Tasmania’s Lake Pedder for hydro-electricity in the 1970s. But the loss of the lake also inspired Australian conservationists to take action, and, notably, galvanised opposition to another proposed dam nearby: that on the Franklin, which was ultimately saved. And now, momentum is building to drain the dam and to restore Pedder to its former glory. Bob Brown, Christine Milne and Tabatha Badger look at the early days of the original campaign, the aftermath of the flooding, and the hope that this great wrong can be righted.

Powerful men lied, cheated and bullied their way to flooding the Lake Pedder National Park in 1972, but citizens raised a heart-rending campaign to save it and, unlike the ardour for its destruction, that campaign is yet to run its course.

Aboriginal Tasmanians witnessed the reformation of the lake, high in the mountains of the Tasmanian wilderness, as the last Ice Age ended 10,000 years ago. Records of an Aboriginal village in the nearby Vale of Rasselas, upstream beside the Gordon River, point to people walking on the lake’s beach millennia before engineers from the Hydro-Electric Commission (HEC) came in the 1960s to flood it.

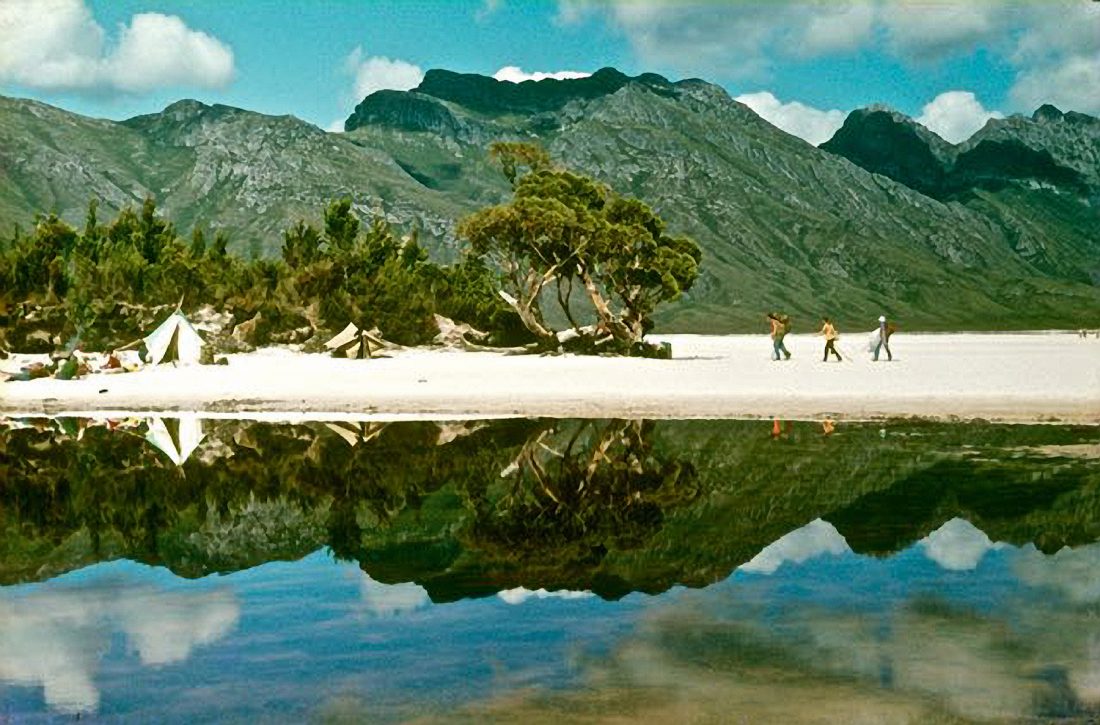

The beach of fine, pinkish-white quartzite sand was more than three kilometres long (the same distance as the Sydney Harbour Bridge to Railway Square) and, in summer, was 800m wide and backed by high, vegetated sand dunes; the latter provided fine camping sites protected from the Roaring Forties winds.

By Dennis Garrett

Within 170 years of the British colony at Hobart, Lake Pedder and its national park, declared in 1955, was obliterated by Tasmania’s rampaging Hydro-Electric Commission. The remarkable sequel is that, fifty years later, the campaign to restore the lake is gathering a winning momentum, a momentum which awaits the political will and common sense of federal and Tasmanian leaders keen on restoring rather than ravaging the wilds. As the people, including scientists, led the lake’s defence in the 1960s and 1970s, so now they lead in its restoration.

A doyen of the campaigners, Melva Truchanas, made many trips to the Lake Pedder National Park. She became chairwoman of the Lake Pedder Action Committee and, now in her nineties, is still an active member of the Lake Pedder Restoration campaign.

Melva was a member of the Launceston Bushwalking Club in 1954 when she met, and later married, Olegas (O-lay-gus) Truchanas. He was a post-war refugee from Lithuania who saw the wild magnificence of his new island home in Tasmania, and set about recording it with his exceptional physical strength and photographic ability. (Ed: Wild ran a profile on Olegas in Issue #172)

Melva and Olegas became aware that the political decision-making had little regard for long-term conservation, and the pair worked to protect Tasmania’s wilderness from development and destruction. “I found a real yearning to be involved in the land and the environment, to appreciate and make sure other people understood that,” Melva says.

The fight to save Lake Pedder from inundation dominated Melva’s and Olegas’ lives for years, and they were hit with some devastating blows along the way. In 1967, the Hobart bushfires destroyed the Truchanas family’s home and all their possessions. That included Olegas’ irreplaceable slides of his exploratory walking and canoeing journeys into Southwest Tasmania.

Olegas set out to recapture his life’s work. Making frequent visits to the lake, he worked with friend (and HEC engineer) Ralph Hope-Johnstsone to create a presentation of his slides—My Pedder—which repeatedly filled Hobart Town Hall and other venues, showing thousands of Tasmanians what they were about to lose.

However, in 1972, while setting off to photograph the Gordon River, Olegas was tragically drowned. He left us this immortal injunction: “Is there any reason why Tasmania should not be more beautiful on the day we leave it, than on the day we came? If we can revise our attitudes towards the land under our feet, if we can accept a role of steward and depart from the role of the conqueror, if we can accept that people and nature are inseparable parts of the unified whole, then Tasmania can be a shining beacon in a dull, uniform and largely artificial world.”

Olegas Truchanas left another enduring gift to the Tasmanian wilderness: He had mentored the shy teenager Peter Dombrovskis in bushcraft, canoeing … and photography. Dombrovskis took the pivotal photographic role in saving the Franklin River a decade after Pedder was lost.

As director of the Tasmanian Wilderness Society during the Franklin campaign years, I was acutely aware not only of the Truchanas’ legacies, but also of the remarkable campaign those fighting to save Pedder had run a decade before ours. The Franklin success in 1983 was founded in their fortitude. In 1985, I produced the book Lake Pedder to salute the Pedder people and help keep their spirit alive.

By Winston Nichols

“Is there any reason why Tasmania should not be more beautiful on the day we leave it, than on the day we came?”

Lake Pedder includes the evocative essay by then-teenage campaigner for the lake Kevin Kiernan, titled ‘I Saw My Temple Ransacked’. (For this edition of Wild, I have had the book digitised. It is copyrighted but feel free to browse. Go to: wild.com.au/conservation/lake-pedder-bob-brown.

1972 was the Pedder campaigners’ annus horribilis. After Olegas’ death in January, the Serpentine Dam downstream of the lake was sealed, and the Serpentine River—which flowed to the Gordon—began damming back across the plains towards the doomed lake. In that summer and autumn, thousands of pilgrims walked or flew in to see the splendour of the lake and beach before they were obliterated.

On 23 March, 1972, at another packed meeting in the Hobart Town Hall, Dr Richard Jones put a motion to establish a new political party to oppose the flooding (Labor and Liberal MPs all backed the destruction). With a show of hands over the cacophony of dam workers brought in to disrupt the meeting, Jones’ motion passed, and the world’s first Greens party was established.

However, under a fusillade of threatening advertising from the HEC, and with news coverage about power price rises (subsequently shown to be false), the new party failed to win a seat in the May state election. ‘Electric Eric’ Reece was elected premier. Reece had famously described mainland bushwalkers as people who came to Tasmania “with one shirt and one five-dollar note, and go home having changed neither”. He glibly maintained the HEC was not destroying Lake Pedder but enlarging it—which led campaigners to dub the proposed artificial lake ‘Fake Pedder’.

By Graham Wootton

The controversy gave rise to street marches, vigils in the Pedder sand dunes, and, in September, the disappearance of campaigner Brenda Hean. She had organised a Tiger Moth flight with pilot Max Price, from Hobart to Canberra, to skywrite ‘SAVE LAKE PEDDER’ over the national parliament. Two nights before takeoff, Hean received a death threat over the phone. The hangar housing the plane was broken into the night before the flight, and the flight beacon removed. The plane disappeared, without trace, over Bass Strait. Reece refused to hold an independent inquiry into what looked like sabotage and murder.

Renowned English expatriate, poet and environmentalist Clive Sansom told me that the campaigners were terrified: “We wondered who would be next. Each morning when I put my foot on the accelerator I worried the car might explode.”

Winter and spring in 1972 brought heavy rain across the Serpentine catchment. The beach was covered, leaving the sand dunes an island arc in the flood. The last defiant campaigner, Chris Tebbutt, was boated off before their tops went under.

“A small solar power station built to replace the deficit … would cost a pittance compared to the gains.”

In December, Gough Whitlam was elected Prime Minister. Early in 1973, influenced by left leader Tom Uren and the new Minister for the Environment, Moss Cass, Whitlam is said to have offered Premier Reece $8.5 million for a last-minute stay of execution for Lake Pedder. The offer was rejected out-of-hand by Reece to the applause of the Tasmanian House of Assembly.

Into this maelstrom stepped Prince Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh and the new president of the Australian Conservation Foundation. He flew over the wilderness to see it for himself, and then met Premier Reece in the state’s parliamentary building. Reece’s biographer Dr Jillian Koshin says “they had a ding-dong row behind closed doors in Reece’s parliamentary office that could be heard down the corridor.” Philip wrote to Whitlam that “the Tasmanian Government simply does not understand the point of conservation.” But the Pedder campaigners did and still do. Bolstered by the recent removal of concrete dams in the USA bigger than those which immersed Lake Pedder, the course of history leads to the lake’s imminent unflooding.

A small (60MW) solar power station built in Victoria to replace the deficit to Melbourne (which currently receives Tasmanian hydro-electricity via the Bass Strait cable) would cost a pittance compared to the gains from having the lake and its beach recovered to the sunshine of wild Tasmania.

As Melva Truchanas puts it: “There is an inevitability about nature. When the dams are decommissioned, nature will prevail.” Lake Pedder’s restoration is on its way.

THE AFTERMATH

By Christine Milne

I didn’t know it at the time but the struggle to save Lake Pedder swirling around me at the University of Tasmania in 1972 would determine the direction of my adult life. From a conservative dairy farming family with nothing but a passing interest in politics, I was naïve enough at 19 to believe that political decisions were evidence-based. Lake Pedder changed that forever. Although unnecessary to meet Tasmania’s energy demand, it was sacrificed to fulfil the engineering dreams of the Hydro-Electric Commission (HEC) to create the Southern Hemisphere’s largest sheet of water. It was the ultimate triumph of ‘man’ over nature.

Lesson learned. I determined then that I’d never let that happen again. We needed a new environmental focus in politics, and so when the HEC announced its intention to dam the Franklin River, I—with thousands of others—went to the blockade, was arrested, and then sent to Risdon Women’s prison. The loss of Pedder radicalised a whole generation of environmentalists who then fought to save the Franklin, and that success empowered us to maintain the struggle and to take environmentalism through grassroots activism and Green politics into state and federal parliaments.

Fast forward to 1994. After the successful campaign to stop North Broken Hill’s polluting, native forest-based, elemental chlorine bleaching pulp mill, I was in the Tasmanian Parliament as Leader of the Tasmanian Greens. I was delighted to give my full support to ‘Pedder 2000’, a campaign to restore Lake Pedder by the turn of the century. There were such high hopes that a new century would usher in an era of big-picture, transformative thinking that would make anything possible. Since 1972, campaigners had kept up the struggle to have Lake Pedder restored, but Helen Gee and Hilary Bennell took it to a new level. The campaign garnered the support of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature at its Congress in Buenos Aires in 1994, and from dignatories worldwide including David Suzuki, David Bellamy and HRH Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh.

A federal parliamentary inquiry in 1995 heard from scientists and experts in all fields that restoring the lake was possible. But opposition to the restoration from the Tasmanian establishment, the HEC, and both the Liberal and Labor parties in Tasmania was intense. They were joined by University of Tasmania aquaculture academic Nigel Forteath, who argued that 4,000 platypus would die if the lake was restored. His claims were disputed by experts in the field; they were nonetheless amplified by a compliant media. The inquiry found it was technically feasible to restore the lake and that doing so would enhance the values of the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area. The political will was absent, however. “It is opposed by the government and the major opposition in Tasmania and under these circumstances has no real prospect of proceeding in the foreseeable future.”

“It [is] technically feasible to restore the Lake and THAT doing so would enhance the values of the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area.”

In spite of the setback, on the 30th anniversary of the flooding in 2002, a time capsule was buried in the impoundment, defiantly containing the hope that the lake would eventually be restored.

Now in this 50th anniversary year of Pedder’s inundation, I am convenor of one of Australia’s longest-running, unbroken campaigns. The rest of the world has caught up, too, with the United Nations declaring 2021-2030 as the Decade on Ecosystem Restoration. Biodiversity loss is a global emergency. We need to protect and restore ecosystems to stem the sixth wave of extinction and to build resilience in landscapes in the face of accelerating global warming. Lake Pedder, in the heart of the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area, is already recognised for its outstanding universal values; it is a perfect global flagship for the UN Decade.

Restoring it would be a sign of healing, and would put Australia on the global map as a leader in ecosystem restoration. It would give our universities the opportunity to engage in the global push for 30% of the Earth’s surface to be protected or restored by 2030, and inspire a generation increasingly anxious about global ecosystem collapse. Furthermore, the 57MW of energy it feeds into the Gordon Power Scheme has already been eclipsed by existing new windfarms, such that its restoration is no threat to Tasmania’s energy security.

A submersible craft revealed in 2020 that the pink quartzite beach and its dune system are still intact, waiting to emerge as the “beacon of hope in a dull, uniform and largely artificial world” imagined by wilderness photographer Olegas Truchanas. Imagine the joy as the thousands of people who have kept jars of Lake Pedder sand and Pedder pennies for half a century restore them to the beach.

In 1974, Edward St John said, “if Lake Pedder were to be re-exposed, its beauty would return, irrespective of the length of time the lake had been flooded. There is, very fortunately in this case, what lawyers call a locus poenitentiae—an opportunity to repent … if not we ourselves, the day will come when our children will undo what we so foolishly have done.”

This is the perfect time for the Federal and Tasmanian Governments to sign off on the restoration of Lake Pedder.

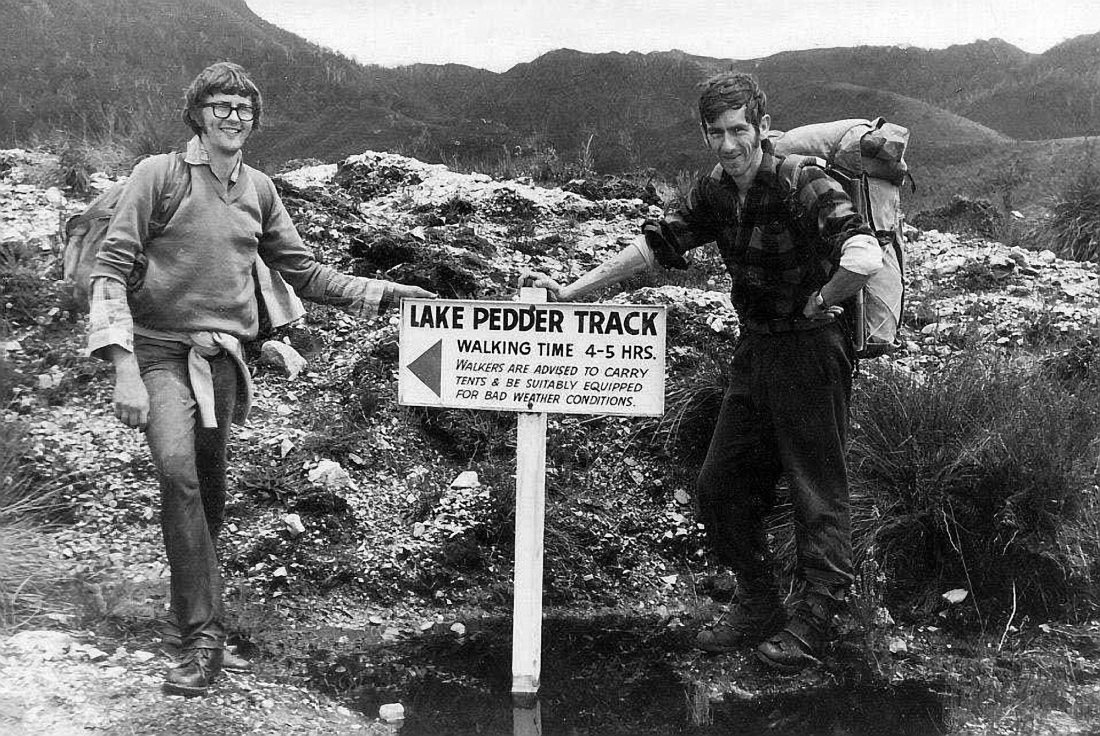

By Lindsay Hope

Reaching remote places requires effort, commitment, and self-reliance. You have to undertake a journey—a journey that may change your perception of the world and of your place in it. The rewards of such journeys can’t be simulated by stepping out of a helicopter. Even if you never visit remote places, it’s heartening to know that they exist, isolated from the pressures and depredations of modern civilisation.

The impact on wilderness of structures like roads and buildings isn’t confined to their immediate footprint. The knowledge that you’re one kilometre from a hut (for example) affects your perception of being remote, even if you never see the hut. Helicopter landings in remote areas degrade the sense that such areas are remote of access, whether or not you’re one of the passengers.

Remoteness also helps to protect an area’s ecological values. Physical distance from disturbances such as logging and land clearing for agriculture helps buffer areas from ecological impacts such as human-lit fires, air and water pollution, and invasive species. Research has shown that the ecological impacts of roads extend several kilometres beyond their immediate footprint.

By Chris Eden

MOVING FORWARD

By Tabatha Badger

For the duration of my lifetime, bushwalking in Southwest Tasmania has centered around the vast inland sea audaciously titled ‘Lake Pedder’. There is barely a rocky outcropped summit in the vicinity from which the darkened waters of the impound aren’t visible.

On a clear, still day, the 242km2 watershed provides glassy, mirror-like reflections of the Frankland and Wilmot Ranges which proudly rise along Pedder’s perimeter. This enlarged Lake Pedder, the Pedder I’ve always known, is beautiful in its own right, and is highly accessible to the public. Yet it looms as an intrusion in this ancient landscape. There is no quaint character to the impoundment, unlike the other elements of the Southwest wilderness. Ultimately, it is just another man-made storage lake, the same as many others found throughout Tasmania and across the world.

Is this sameness of hydro dams the reason for decreasing visitors to Pedder? Despite being one of the few sites with drivable access in any world heritage wilderness area, estimated annual visitors have dropped from 68,000 just after Pedder’s flooding in the 70s to just 15,000 in the 2000s, with a minimal rise to 19,000 in the ‘Great Tasmanian Tourism Boom’, pre-COVID.

But Pedder is not only functioning poorly as a tourism destination, it’s barely being used for power. Because of legislation to prevent shore erosion and to retain aesthetic values, during the energy supply crisis of 2015-2016, the Tasmanian Government chose not to lower the minimum drawdown level of Pedder to impart water into neighbouring Lake Gordon, despite the fact that doing so would have provided Tasmania the power it needed.

It’s worth then asking: If tourism is faltering, and if we will not use the lake for power even when absolutely necessary, then why keep the impoundment at all?

By Lindsay Hope

The 2015 Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area Reactive Monitoring Mission identified the enlarged Pedder and its hydro infrastructure as devaluing the World Heritage site’s integrity; under the World Heritage Convention, Tasmania is obligated to restore degraded sites where possible. Restoring Pedder is not just possible, however; I believe it’s inevitable.

The question is when.

When will Lake Pedder’s famous glittering quartzite beach re-emerge? In 50 years, when the government concedes the already excessive costs of dam maintenance have become too much? Perhaps it will re-remerge after the next earthquake within the Edgar Fault Line, upon which two of the dams impounding Pedder are precariously built? Or could it be now, amid the climate and biodiversity crises, when the world needs positive, ambitious change to fundamentally shift and challenge the way in which we consider our relationship with the natural world?

The growing cohort of young adventurers nationwide calling for Pedder’s restoration not only debunks the myth that the proposal is a nostalgia trip for old green bushwalkers, it is proof the original lake transcends traditional place values to inspire a generation—a generation who have inherited enormous environmental destruction and biodiversity loss—to fight for ambitious change. Lake Pedder’s flooding initiated a new era of environmental conservation politics; imagine what restoring Pedder will instigate!

What it would be to clamber over the boulders onto the Eliza Plateau and see the rehabilitating landscape below where the impoundment once was, knowing the next generation of adventurers will roam Pedder’s shore searching for Pedder Pennies, swim in Maria Creek and meander for hours through the shallow tannin-stained shore, with its distinct herringbone pattern.

When we dismantle the dams, (and let’s re-use the material for walking tracks), we will reinstate the integrity of the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area and revive an icon considered as significant as Uluru or the Great Barrier Reef. There are thousands of other impoundments to adore. But there is only one Lake Pedder. Why not restore the jewel of Tasmania’s Southwest?

By Winston Nickols

CONTRIBUTORS:

Bob Brown – Patron of the Bob Brown Foundation & Former Leader of the Australian Greens

Christine Milne – Convenor of the Lake Pedder Restoration Committee & Former Australian Greens Leader

Tabatha Badger – Tasmanian bushwalker and photographer, Secretary of Lake Pedder Restoration Committee

FURTHER READING: lakepedder.org

If you liked this piece, you should subscribe to the print mag. Only a fraction of the great stories we run in the mag make it to our website; if you want to read them, head to subscribe.wild.com.au.