Western Australias northern jarrah forests

The ongoing expansion of bauxite mining in Western Australia threatens both the environment and numerous bushwalking routes.

Words & Images: Dave Osborne

(This story originally featured in Wild #182, Summer 2021)

Western Australia’s unique northern jarrah forest and wandoo woodlands of the Darling Range, on the fringes of the Perth metropolitan area, have long been the go-to destinations for locals seeking traditional bushwalking opportunities within easy distance of home. The beauty and amazing diversity of the flowering shrubs rewards the visitor with a great array of wildflowers in springtime. The mostly light and open forests and woodlands are ideal for minimal impact, off-track bushwalking. ‘Bush-bashing’ is not required to walk cross-country through these forests!

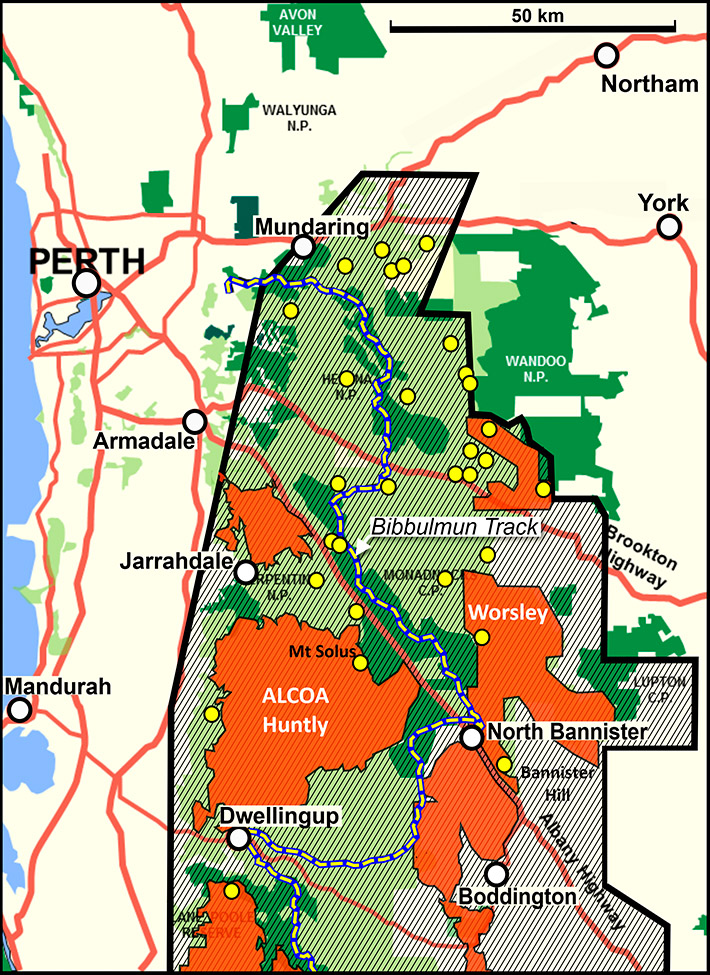

Yet one after another, customary routes long favoured by bushwalkers are disappearing. Over the course of the next forty-or-so years, at least thirty known bushwalking areas will be—or have already been—diminished, ranging from Bannister Hill and Mount Solus in the south, to the Manns Gully-Chinamans Gully and Hancock Brook areas in the north near the town of Mundaring. Significant sections of the popular Bibbulmun Track will also require re-aligning through (at best) narrow buffer zones intended to screen out the reality of a degraded environment.

The culprit? Bauxite mining.

Shallow bauxite ore—the source of aluminium—blankets much of the uplands of the northern Darling Range. Strip mining for bauxite commenced near Jarrahdale in 1963. Initially the rate of land being excavated was small—roughly four hectares a year. But that was before the state government approved major expansions of mining operations. Alcoa’s Huntly operation—now the world’s second-largest bauxite mine—alone has an approved gross mining envelope of over 600km2. The mining mosaic within that envelope is now expanding at over 3000ha per year. With long-term bauxite mining leases near Perth covering an area of almost 10,000km2, and with operations expected to continue until 2070, over 60% of the forests and woodlands close to Perth will have been directly impacted or fragmented by mining.

Although some of the land area within Alcoa’s 7000km2 lease is protected within existing national parks, or will likely be included in proposed national parks, most of the tall, high-quality jarrah forest areas remain unprotected as state forest. Alcoa has previously claimed that “over an expected 100-year or so life of the viable bauxite reserves, [the company] will have disturbed [only] 5.6% of the northern jarrah forest.” Today, satellite imagery across the Huntly operation reveals that the actual disturbance is already much greater.

Vast areas of mature forest habitat on Perth’s doorstep are being lost. A forest that was able to survive the intense-but-selective logging of the early 1900s, will not show the same resilience to 100 years of the much more extreme impacts of bauxite strip-mining.

It’s not just the loss of trees that’s at issue. In a 2007 article ‘Bauxite Mining in Jarrah Forests’ Roger Underwood, a former General Manager of the then WA Department of Conservation and Land Management (CALM), noted that “Apart from the loss of native forest, there has been a significant loss of run-off into streams and dams in the mined-over catchment areas. Pits have been designed to retain rather than shed rainfall, so run-off to forest streams is close to zero, and in many cases old mine pits cover nearly 50% of each sub-catchment. This has obvious impacts on water resources and aquatic ecosystems.” This has been confirmed by the CSIRO, which has measured substantial decreases in water yield from mined catchment areas. The cost to the state to boost desalination to replace this loss in drinking water availability may annually exceed the royalties paid to the state by the miners.

Yet the broader impacts of the mining have been mostly ignored since the early 1980s following a concerted-but-unsuccessful battle by conservationists to stop mining expansion. The State Government’s recently announced ban on native forest logging from 2024 will save an additional 4000km2 of the southwest forests from logging, but unfortunately will still not prevent the destruction of much of the northern jarrah forest. Future demand for native hardwood timber is expected to be met in part by continued, government-approved clearing of the forests for bauxite mining expansions.

In situations of potential catastrophic outcomes, governments typically rush to apply the precautionary principle. Why not here also?”

But in recent years, there has at least been growing public awareness of some local impacts. In particular, the communities of Jarrahdale and Dwellingup, south of Perth, have expressed their alarm about the environmental and social implications of the current mining-expansion proposal for their ‘trail town’ aspirations.

Part of the problem of protecting the northern jarrah forest arises from the parallel operations of WA’s Forest Management Plan, the state’s agreements with the miners, and WA’s Environmental Protection Act (EPA). These often result in strongly conflicting priorities and decisions with regard to the goals of conservation and sustainable social opportunities, including for recreation.

A federal senate inquiry on mine rehabilitation in 2018 also revealed that the agreements that companies such as Alcoa operate under in WA result in contradictory situations in environmental planning, and in some cases override federal environmental controls. An asset such as aged forest—providing nesting hollows for endangered black cockatoos—took hundreds of years to develop. Yet the miner has been able to remove vast areas of black cockatoo habitat without being subject to the constraints of the federal act.

Yes, Alcoa’s 2020 proposal to expand mining around the Huntly area—which would increase the overall mined envelope between Jarrahdale and Dwellingup to over 800 km2—will now be subject to a Public Environmental Review (PER). However, given the profound changes and major upscaling of the strip-mining operations since their inception over 55 years ago, the more appropriate course would be for the government and the EPA to now require a full, lease-wide review of the environmental and social costs of its 100+ year mine-life, rather than the much narrower PER process which will focus only on the current expansion proposal.

Despite the miner’s claims of global excellence in rehabilitation of mined native forest areas, the reality is that their best efforts remain a long-term experiment with a high risk of an enduring, disastrous environmental outcome for WA’s unique northern jarrah forest. We would be gullible to accept any assurances that the young replacement forest will thrive in the longer term. The quick re-seeding and re-greening of the degraded and ripped landscape with a diversity of local plant species may give the impression to the general public that the natural environment is being successfully restored, but no one can know whether this substitute forest will ultimately survive, let alone thrive, on the drastically altered substrate.

In situations of potential catastrophic outcomes, governments typically rush to apply the precautionary principle, as in water catchment access policy and COVID-19, zealously arguing that where extensive scientific knowledge on a matter is lacking, there is a need to exercise maximum caution. Why not here also?

Eighty percent of WA’s population lives in the Perth region, and Perth’s population has grown by over 50% during the past quarter century. Continuing growth will drive increasing demand for access to natural environments near the city. Will the environmental and social values of the remaining northern jarrah forest be recognised and properly protected before it’s too late? Or will Roger Underwood’s words of 14 years ago prove prophetic: “… [T]here will come a time in the not-too-distant future when West Australians realise what has gone on, and the extent and cost of the ecological damage which has occurred. Then perhaps they will look back on the … destruction of the jarrah forest by bauxite mining as one of the greatest conservation blunders in our history.”

CONTRIBUTOR: Dave Osborne is the President & Acting Executive Officer of HikeWest (previously Bushwalking WA), and author of popular WA bushwalking site walkgps.com.au

If you liked this piece, you should subscribe to the print mag. Only a fraction of the great stories we run in the mag make it to our website; if you want to read them, head to subscribe.wild.com.au.