Luxury Lodges Means Wilderness Lost

Our national parks are under attack. Privatisation, in the form of luxury lodges and other accommodation for walkers, has gained nationwide momentum. In this, Part I of a two-part series, we look at breadth of the problem across the country.

Words: James McCormack

(This story originally featured in Wild #178, Summer 2020)

Title photo: Walls of Jerusalem from Lake Malbena, Tasmania. Credit: Grant Dixon

“We all come from wilderness. That’s why we love nature. It’s why we delight in flowers and seeing wildlife because it’s part of our genetic structure. Now we live mainly in cities, where wilderness has been 90% or totally destroyed. It’s arguably the fastest disappearing natural resource on the planet. That’s why it’s such a premium. As it’s become less available, it’s become more valuable for exploiters.”

Bob Brown, in a personal conversation with Wild.

“A couple of rich bastards want to come into our parks and ruin everything.”

Geoff Dixon—ex-Qantas CEO and co-founder of the Australian Walking Company, and one of the rich bastards who wants to come into our parks and ruin everything—quoted in the Financial Review.

Earlier this year, wanting to take my young son on a longer walk of four or five days, I recalled reading about the 65km Green Gully Track in NSW’s Oxley Wild Rivers NP. It sounded pleasant. The National Parks and Wildlife Service’s (NPWS) website extolled the track’s virtues—a unique journey into the Apsley-Macleay gorges, one of Australia’s largest gorge systems. It mentioned fern-lined gullies, high elevation forests, and wildlife. It also mentioned there were historic huts to stay in. Since staying in them cost $6001—and remember, I’m the editor of Wild; I hardly earn a corporate salary—I figured we‘d just camp.

But when I searched to see what campsites were on the route, I couldn’t find any. And that’s when I learnt we couldn’t just camp. Despite this being a national park—a public park—if you don’t pay or can’t pay the $600 (because you’re a student, unemployed, or simply not flush with funds), well, you’re out of luck. You can’t do the walk. It seemed so outrageous that, at first, I wondered if I’d read it incorrectly, so I rang the relevant NPWS District Office. I wasn’t mistaken. No pay, no walk. The ranger sheepishly said something about this being “the business model.” I was incensed.

Now I could argue that if my taxpayer dollars are funding this park, I should have the right to access it. But that’s not really the point; the unemployed, students and the poor should have equal rights to access this track, whether they pay a dollar in tax or not. This is public land.

A few days after this, I happened to be speaking with Bob Brown, bitching about this state of affairs. It wasn’t just the Green Gully Track; I was also angry about proposals on NSW’s South Coast to shut down hitherto long-used campsites so private huts could be built. I was aware, too, of the furore over Tasmania’s Lake Malbena, where it’s proposed helicopters will ferry the well-heeled out to Hall’s Island. I had heard—though knew few of the actual details—of the outcry over lodges proposed in Kangaroo Island’s Flinders Chase National Park. And I have long been troubled by Tasmania’s Three Cape’s Track, where luxury lodges were built in wilderness, with campsites long used by local bushwalkers shut down as part of the deal.

All this I knew. It turned out, however, I knew little. My outrage turned to horror as Bob began telling me of proposals for lodges along the length of Tasmania’s iconic South Coast Track (SCT). The South Coast Track is not just any walk. It is beauty and wildness writ large. It is about challenge, about dire weather, about lashing rains and deep mud, and yes, it is about discomfort. And then Bob mentioned another proposal for private lodges in a national park, this one up on Queensland’s Hinchinbrook Island.

“It’s a really dodgy process that fundamentally is about transferring public land for basically peanuts to someone to make a buck from.”

And what became apparent to me during that conversation is that while the fights against private accommodation within our national parks are happening park by park, or, at best, state by state, most proponents of them—like our peak tourism bodies; like Brett Godfrey of the Australian Walking Company (AWC), which operates lodges under the banner of the Tasmanian Walking Company (TWC) on the Three Capes Track, and has proposed others elsewhere in Tasmania, as well as at Uluru, Hinchinbrook Island, Kangaroo Island and elsewhere—are taking a far broader approach. This alienation of public land by people whose prime concern is not environmental protection but instead profit isn’t just happening here and there. It is a nation-wide plunder. This is the theft of Australia’s wilderness. To be clear, this is theft in a metaphorical sense; I’m not suggesting laws have been broken. But in some ways, that’s almost worse; the fact our legal framework aids and abets this is both distressing and appalling.

But although laws may not have been strictly broken, as The Wilderness Society’s Tom Allen told me, “We’ve seen just so many instances of rule bending, and a really dodgy process that fundamentally is about transferring public land for basically peanuts to someone to make a buck from.”

OF ALL THE ISSUES FACING US TODAY, private accommodation for walkers within national parks—i.e. huts and lodges—might seem an unlikely locus for an ideological nexus, but the proposals at hand are the sites of confrontation for myriad tensions, some at the very core of our worldviews: private/public, rich/poor, industrial/natural, materialism/spirituality, development/wilderness, exploitation/conservation, luxury/stoicism, dependence/independence. The list goes on.

Commercialisation of our national parks goes far further, of course, than just huts. And yet what’s happening with them is emblematic of the pressures placed on our natural heritage. In some ways, I’ll argue, this goes far deeper than fighting to keep wild places wild, or fighting to preserve ecological integrity, although those reasons should alone halt these developments.

But up front, I’m going to state my bias. As I see it, the provision of new infrastructure—and that includes accommodation—within our national parks should be the preserve of public authorities. Period. I have nothing against luxury accommodation per se—I don’t mind the odd fine wine and hot tub myself—but this, even to the extent of semi-permanent ‘glamping tents’, should be on private lands. Again, period. Anything more than temporary crosses that line. Bob Brown, in our chat, put it simply: “Inside parks—government infrastructure for the people. Private infrastructure—outside parks.”

Actually, I may as well state one other bias: I’m not outright against huts on public lands. But they shouldn’t be prolific. They shouldn’t be privately owned. If huts are to exist, they should be similar to those in NZ’s network of Department of Conservation huts: publicly-owned, non-exclusionary, low-key, simple, and sited in appropriate locations. The motive for their creation should be utility for park users, not profit. Unfortunately, that list of caveats rules out every proposal I’ll soon mention.

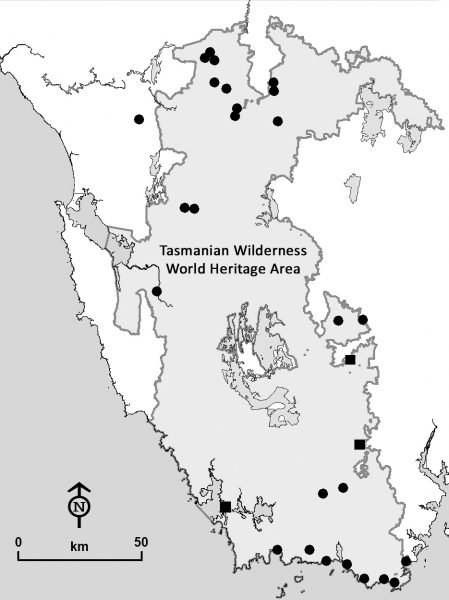

Some will disagree with those opinions. Others, although in large agreement, might have a more nuanced view. But it’s not just the precedent-setting, or the give-an-inch-take-a-mile, or the slippery-slope arguments, important as they all are, that’s induced my black-and-whiteness here. Partly it stems from the fact that in the months subsequent to that chat with Bob, I’ve since—to get a better idea of what’s happening—spoken with dozens of people around the country about it. And it’s worse than I imagined. In Tasmania, for instance, not only are Lake Malbena and the South Coast Track being targeted; Frenchmans Cap is in the cross hairs. So, too, the Walls of Jerusalem. The Tyndall Range as well. Elsewhere, Queensland’s recently-opened Scenic Rim Trail has new private lodges. More are planned along the Thorsborne Trail in Hinchinbrook NP, the Cooloola Great Walk in Great Sandy NP, and the planned Ngaro Track in Whitsunday Island NP. Private accommodation for walkers has been proposed within Victoria’s Gariwerd/Grampians NP. Virtual villages are envisaged for pristine wilderness in SA’s Flinders Chase NP and Victoria’s alpine high country.

The scale for these developments vary. Some are worse, by far, than others. Some exclude independent-tent based camping; others co-exist with it. Some are for semi-permanent tents and eco-pods (chuck the marketers weasel-word ‘eco’ in front of anything and it becomes more palatable). Some are for public huts. Others are for private large-scale luxury lodges; calling them ‘huts’ ludicrously understates their size. Many go further still, involving perhaps nine structures, perhaps a dozen. I say perhaps because, all too often, authorities—citing commercial-in-confidence—keep the public in the dark about these proposals until unveiling them as fait accomplis. Quite frankly, all these developments warrant individual feature stories in Wild. But it’s crucial we understand this as a national phenomenon, even if doing so means omitting important details of individual instances.

Let’s start, then, with Tassie’s Three Capes Track; it’s the model for many developments elsewhere. As Tom Allen told me, “the DNA behind a lot of these proposals was first developed in Tasmania. [And] like a virus, it’s being replicated around the country.” The track was opened in 2015, a three-day walk on the spectacular Tasman Peninsula. There’d long been a rough trail in the area, but as part of the project it was upgraded and rerouted, and both private and public lodges were built along it—three operated by the Tasmanian Government as part of the Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service, and two by the Tasmanian Walking Company (aka the AWC).

Neither option comes cheaply. Choose your poison: $495 for the public huts; or $2,895 (or more) for the TWC’s plush lodges2. But there were bigger costs still, one being the cost borne by local bushwalkers who saw access to their long-used campsites on Cape Pillar removed; they’re now forced to camp nearly ten kilometres distant in locales far less spectacular. Granted, some of those campsites were becoming degraded. That, however, could have been rectified without closure.

“As Bob Brown said during our chat: “A wilderness lodge is a non-sequitur.” Once the lodge is there, it’s no longer wilderness.”

The biggest cost, however, was that of wilderness. When I spoke with Grant Dixon—long-time Wild contributor and co-author of Refining the Definition of Wilderness—he told me that the Tasman Peninsula was Tasmania’s East Coast’s sole area of defined wilderness. “This was a rare walk. But construction of this track [means] there’s now no wilderness on the peninsula.”

Some might wonder how huts could so impact wilderness. But these aren’t just ‘huts’. Their scale is astonishing. Ryan Hansen, another frequent Wild contributor who’s walked in the area, told me: “The first building we saw, we thought, ‘That’s fancy’. It turned out it was the toilet block. The lodge seemed ridiculous, just nuts. It was monumental. It felt like a small town.”

Walking isn’t necessarily the lodges’ drawcard. In fact, TWC’s sales pitch enthusiastically says, “Those with a penchant for pampering can forego today’s walk and spend the day at Cape Pillar Lodge.” There’s a clear implication: Enabling walkers isn’t the real goal; the real goal is providing private luxurious lodging within an otherwise wild environment. Again, there’s nothing wrong with luxury, just provided it’s outside park boundaries.

And the walking, well, that too no longer feels like wilderness walking. It feels like you’re on a path. One through stunning country, no doubt, but as Chris Armstrong—another Wild regular, and who guides in the area—told me, it feels “industrial”. “You do not dodge a rock. You cannot trip over. You’re on boardwalk, compacted gravel, or hand-hewn rock. It is brutally hard on your feet and your legs. I do a lot of walking, and the track to Cape Pillar is one of the hardest—as in concrete hardest—tracks I’ve ever walked.”

There’s another element here: this loss of wilderness is not accidental. Brett Godfrey, quoted by the ABC, said his target demographic was a “52-year-old single female who finds going into the wilderness not her cup of tea”. What’s Godfrey’s answer? It isn’t to take his clients to appropriate locations; it’s to make locations ‘appropriate’ to his clients by removing wilderness from the equation. As Bob Brown said during our chat: “A wilderness lodge is a non-sequitur.” Once the lodge is there, it’s no longer wilderness.

Godfrey isn’t alone in trying to rid Tasmania of its pesky wilderness. That effort goes to the state’s very top. The Tasmanian Wilderness WHA is the only World Heritage site on the planet with the word ‘wilderness’ in its name. When he was premier, however, Will Hodgman tried to change that, running a campaign to expunge the word wilderness from the name.

But proposals are afoot to do more than remove wilderness in word; they aim to do it in deed. Grant Dixon alerted me to the ‘Tasmania – Gateway of Opportunities’ website. Go there3, and see for yourself the dozens of already-approved developments that—if they proceed—will transform Tassie’s national parks and, in particular, change the Southwest forever.

Not all are accommodation proposals. But of those that are, even if just a few proceed, the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area will be utterly compromised. The best-known proposal is to develop Halls Island in Lake Malbena by constructing a ‘standing camp’ with fly-in helicopter access. (As Darryl Kerrigan would say, How’s the serenity!) The plan caused outrage. Widespread protests ensued, and when the local council advertised the Development Application, it received 1,346 submissions; just three supported it. (It’s been noted elsewhere that three is also the number of full-time jobs the development would create.) Council rejected the DA, but—running roughshod over legal protocols—Tasmania’s Resource Management and Planning Tribunal overturned that rejection. After appeals and counter-appeals, in September 2020 federal Environment Minister Sussan Ley intervened to at least make the application process adhere to the law, forcing it to be assessed under the EPBC Act. The proposal as of writing remains under consideration.

As bad as Malbena is, (and it’s bad) other developments are arguably worse. Take, for instance, the plan to construct six huts along the South Coast Track, utterly compromising one of Australia’s most challenging walks4. “It would be,” says Grant Dixon, “a disaster.” What happened on the Three Capes, he says, “would be relatively minor compared to what would transpire on the South Coast.” Now, the question may be—and it’s a valid question—how does one person’s activities affect the mindset of another? Surely someone else staying in a lodge shouldn’t alter your experience of staying in a tent. It’s true. In some ways, it shouldn’t. But it does. It’s a fundamental flaw in the human psyche, but there’s no doubt that for most people, seeing others travel in ease while you travel in more challenging circumstances affects your experience. It’s for that reason putting a road, or steps, or ladders, to a peak’s summit devalues the climb for mountaineers.

But it goes further still. How will these lodges be serviced? How will gas for cooking be transported to them? Wine? Food? Clean linen? How will lodge guests’ poo be shuttled out? The obvious answer is by helicopter, thus ruining the wilderness experience of independent walkers. Grant Dixon told me the 2016 management plan made provision for five helicopter landing sites in the Southwest. But who knows? There could be more. Again, the public is kept in the dark. In any case, presuming Malbena is one site, where are the others? The proposed SCT lodges are obvious targets.

Then there’s the track itself. Will it, for commercially viability, be ‘defanged’? Will the mud need to go? Will it need steps? More duckboarding? More hardening? Will it be necessary to “industrialise” it like the Three Capes Track, so that it’s not so much track as hardened path? And if choppers are ferrying in grog, grub and linen, will they soon bring lodge guests to ameliorate the costs of flying? Which, of course, will lead to more choppers. The sky over the once-wild Southwest will be buzzing. The notion of wilderness for independent walkers here will be forever destroyed.

There’s further absurdity, Bob Brown told me: “Not only is the developer putting double-storey luxury villas with helicopter pads along one of the wildest, most scenic and remote walks on Earth; he’s being given three or four million dollars of public money to do it.”

The proposals don’t stop at the SCT. Private lodging is proposed for Frenchmans Cap. In the Walls of Jerusalem. In the Tyndall Range. We’re facing the Southwest’s wholesale gutting. And with more private accommodation proposed for the Overland Track, it’s worthy noting that Bob Brown and others opposed the original decision many decades ago to allow private huts along the track. “It was clear it was the thin edge of the wedge.”

NOT ALL THOSE PROPOSALS INVOLVE LODGES; some are for glamping-style pods. But here’s the thing: Are they, too, the wedge’s thin edge? Will they be glamping tents one day, villas the next? Because that’s what happened in Flinders Chase NP on SA’s Kangaroo Island. I spoke with Bev Maxwell, spokesperson for ‘Public Parks, Not Private Playgrounds’ (see their logo at this story’s head), a group formed to oppose the Australian Walking Company’s plans to build in the park what Bev and others call “villages”. A few years back, she told me, the state government invited proposals from businesses to provide facilities in SA’s national parks. In response, the AWC proposed glamping accommodation along the Kangaroo Island Wilderness Track. Locals uneasily accepted the plan; at least the glamping was at campsites within appropriate management zones, and would be—and this is the crucial word, Bob Huxtable, another KI local, told me—near the track. But at the project’s final unveiling, the community, excluded from the planning process, was horrified; the plan had changed significantly.

The glamping tents, well, they were now permanent structures. And they were no longer to be co-located with other campsites. They were now far off the track; considerable extensions to the trail would be needed. Worse yet, the proposed site locations were shocking. Just two structures exist along Flinders Chase NP’s almost 100km of coastline: Cape Borda and Cape du Couedic Lighthouses. But with the AWC’s proposals for coastal developments at Sanderson Bay and Sandy Creek, that would change.

Sandy Creek, in particular, is a vulnerable but until now untouched pristine area. Bev told me it’s “magical.” But what’s proposed there, she said, “is a village comprising ten buildings on the headland…stuck up where people can see them.” Getting supplies to the village—with satellite huts clustered around a main structure nearly 20m long—needs construction of a nearly three kilometre vehicular track. Significant vegetation clearing would also be necessary, and there’d be disruption to animals like the endangered Kangaroo Island dunnart, whose habitat has been identified near the sites. Need I remind you—this is all within a ‘protected’ national park.

Locals were incensed. Surveys showed opposition to the plan ran as high as 97%. The Flinders Chase chapter of Friends of Parks—an SA volunteer organisation dedicated to assisting the state’s national parks—went on strike, withdrawing their labour. And some rangers resigned. That’s right, people actually quit their jobs. Additionally, a range of traditional, sometimes conservative groups came out publicly against it: The National Trust, Friends of the Heysen Trail, Friends of the Museum, the Nature Foundation, the Field Naturalists Society. But as Bev said to me, “If this goes ahead, there there’s no park in South Australia that’s safe.”

Protest rallies with hundreds of participants were held in Adelaide. Opposition to the proposal, Bev told me, “really crossed boundaries, politically, socially, as well as age. People spoke to me saying, ‘This is the first ever rally I’ve been to in my life.’”

A local group, Eco-Action KI, took both South Australia’s Department of Environment and Water and the AWC to the state’s Supreme Court. “Our argument is that three kilometres is not near,” says Bob Huxtable. Fraser Vickery, also involved with Eco-Action, told me, “Fundamentally, it’s a planning objection. The management plan and zoning doesn’t allow for the scale and nature of this development.” The fight is ongoing, and there have been multiple adjournments. The case will likely be heard in the state’s Supreme Court in May 2021.

Queensland is another state where government initiated a public land sell-off. I spoke with David Haigh, who taught environmental law at James Cook University for several decades. He explained that in 2018, Kate Jones, Minister of Tourism, called for tenders to develop private tourist resorts along walks in three national parks: The Thorsborne Trail in Hinchinbrook NP, the Whitsunday Trail in Whitsunday NP, and the Cooloola Great Walk in the Great Sandy NP. All run through World Heritage Areas. “But on what basis,” asks Haigh, “does the Minister of Tourism, not the Minister for Environment, claim jurisdiction over national parks? The Nature Conservation Act is clearly intended to be run by the Department of Environment.”

It’s worth noting that a year prior, the Palaszczuk Government made a pre-election commitment NOT to allow such development in national parks. But why stick by the promise once re-elected? To kickstart the privatisation process, the government offered significant incentives. Approvals would be fast-tracked. And whoever won the Whitsunday Island Trail contract would receive up to $5 million in taxpayer funds to assist ‘eco-accommodation’ construction. As in Tasmania, taxpayers would be slugged to help private companies turn a profit by alienating that same taxpaying public from its own lands. And while technically the land along the trails isn’t being ‘sold’—it’s being leased—those leases run for 60 years; in essence, these are de facto sales.

There’s another twist here. The Chair of Tourism and Events Queensland—the government body that recommended these projects—was none other than Brett Godfrey, who as an AWC Director potentially stood to gain significantly from them. The conflict of interest is obvious. “But Godfrey,” Bob Brown told me, “claims to have a firewall in the middle of his brain so that one thing doesn’t influence the other,” before adding, “You can believe that if you want to.” Most don’t. “It’s a clear public interest problem,” David Haigh told me. “When it goes to tender, who gets the profit? He does. A public servant!”

The most significant resistance to development along the trails in question has been with respect to Hinchinbrook’s stunning Thorsborne Trail. When the plans were announced, the local community rose up. Crystal Falknau—a representative of the Townsville-based North Queensland Conservation Council (NQCC)—told me locals had memories of an earlier alienation of national park land on Hinchinbrook: the Cape Richards Resort, which now lies in ruins years after being destroyed by Cyclone Yasi. Falknau added, “Once the Thorsborne Trail is no longer under public ownership, its future is really uncertain. It’s an area that should belong to anyone and everyone, not private interests.” And then there’s the threat to Hinchinbrook’s wilderness nature, which, Laura Hahn—Conservation Principal of National Parks Association of Queensland (NPAQ)—told me, “is incompatible with private development.”

There’s hope, at least; Falknau told me it appears the Thorsborne project is languishing, with development timelines not being met. But while it—and the Whitsunday and Cooloola projects—seemingly stagnate, in the meantime, Queensland’s first instance of private accommodation along a national park walking trail has occurred elsewhere: on the Scenic Rim Trail in Main Range NP. The SRT only opened months ago, and in this very issue we’re running track notes on it for independent bushwalkers.

“If you think that commercial development within [Queensland] National Parks is for the public good, then think again. This is about Government caving into commercial interests.”

It’s a beautiful walk, but strung along it are collections of lodges. Some are outside the park; I have no problem with them. In fact, they could be considered good examples of siting accommodation beyond park boundaries. Two, however, are within park lands. Both have ten buildings. Looking at the brochure, the cabins at Timber Getters seem lovely. But at $3,390 for five days, they should be, I guess. What they shouldn’t be, however, is within a national park. As Tarquin Moon of the NQCC has said, “If you think that commercial development within [Queensland] National Parks is for the public good, then think again. This is about Government caving into commercial interests.”

It was mainland Queensland’s first private development in a national park in over 110 years. Much of the planning process took place in circumstances the NPAQ called “opaque.” Citing a gap in transparency, NPAQ’s Laura Hahn told me, “[we have] been fighting for a community say on proposals for private development in national parks. The community has a right to know all impacts.”

There is, however, some nuance to the SRT (even if the within-park lodges shouldn’t have been allowed); unlike most other proposals, there have been some gains for the general public. I chatted with John Marshall of Bushwalking Queensland, and while having reservations about private development in parks, he said in this specific instance the new track and three new campsites for ‘freedom’ walkers meant there were positives as well.

At the opposite end of the spectrum in terms of expanding benefits is what’s happening in NSW, where the goal seems to be to reduce options for independent tent-based bushwalkers. And it’s not private enterprise doing the land-grabbing; it’s government. The Green Gully Track I mentioned earlier is the worst example of this perhaps anywhere in the country; it’s the only instance I know of that allows no independent walking whatsoever. Pay $600 for the huts, or don’t walk5.

But there’s another proposal that’s stirring outrage: the Light to Light Track on NSW’s Far South Coast. Running for roughly 30km in Ben Boyd NP between Boyd’s Tower and Cape Green Lighthouse, the track is planned to be ‘upgraded’; that process involves constructing two new accommodation sites—run by the NPWS—along the route.

Mowarry Point, long used as an unofficial campsite by local bushwalkers, is one of the sites. I spoke with John Blay, author of Wild Nature—a poetic, insightful, ruminative exploration of the forests and coastlines of NSW’s Southeast and Victoria’s Gippsland regions; the book highlights many instances of the area’s national parks being sabotaged, including along the Light to Light—and he told me Mowarry was a beautiful spot: a small scoop of grassed hillside running down to a little, classic beach.

It seems only natural people would want to camp there. But actually, along the entire stretch of coast there are, John told me, “lots of beautiful little [spots] amongst the melaleucas or down along the shoreline where you can have a primitive campsite and without mucking it all up. It’s been working really well so far.”

That will end with the upgraded Light to Light Track. All primitive campsites—including the long-used one at Mowarry, and the one Hegartys Bay, which, incidentally, is the site of the second lodge—will be closed; bushwalkers will be herded into two campsites near roads. To be fair to National Parks, some closures are likely driven out of environmental concerns. But if Mowarry Point and Hegartys Bay are ecologically able to sustain lodges, surely they could support camping, too. And if some of these campsites do indeed have environmental issues, can’t they be ‘hardened’ by creating tent platforms rather than herding all walkers into just two sites?

“From my perspective,” Gary Dunnett—Executive Officer of the National Parks Association of NSW—told me, “it’s putting the cart in front of the horse. They’ve got an existing strong user base for the park, and they’re trying to create a boutique experience. But rather than that being a low-impact addition to the existing user base, it’s actually supplanting it. It seems perverse, to be blunt.”

It’s hard not to be cynical here, as indeed it is with Three Capes: To what extent are campsites being closed to make lodges commercially viable? Why pay for views—the thinking would go if the campsites remained—when just around the corner you can get a similarly superb view for free? And on the subject of commercial viability, there’s the fact that with the precedent set it’s not at all implausible—in fact it’s incredibly easy—to envisage a scenario where the NPWS decides it’s not making enough profit, and so sells them off to a private-for profit operator like AWC. That likelihood actually rises if they are profitable; the state government would then gain far more from their privatisation.

Victoria seemed headed for a similar but more extensive system of publicly-owned huts along the still-being-constructed Grampians Peak Trail. But when I chatted with Phil Ingamells of the Victorian National Parks Association, he told me that, in the face of opposition, hut proposals had been scaled back; for the time being, it seems only some semi-permanent, glamping-style accommodation at one end of the track is being developed. The key question is whether that expands over time. But Phil then brought up a more imminent Victorian threat: the Falls to Hotham Track. Four accommodation ‘nodes’ are proposed along the five-day track. At least, unlike some other proposals, independent camping will still be allowed both away from the nodes and—apparently—at the nodes themselves, where huge hut complexes are planned. As with Flinders Chase, characterising them as villages wouldn’t be amiss. There will be large central communal buildings surrounded by perhaps a dozen satellite huts, and the Master Plan’s preferred model is for them to be privately operated for the benefit of private walking tours.

The node of most concern, Phil told me, is on Diamantina Spur near Mt Feathertop. “Feathertop is the only sizeable freestanding mountain in Victoria,” said Phil. “This would be a real intrusion on it.” Getting walkers up this, the steepest walkers’ approach to the peak, involves constructing a new, enormously expensive track. Getting supplies up there would be a struggle, too. To that end, it’s proposed helicopters will service the node. If the hut complexes alone don’t alter the entire wild high country’s ambience, it’s hard to see how choppers won’t. But the whole walk, Phil told me, “wasn’t Parks Victoria’s idea; it was the tourism industry’s. They said they needed a spectacular view and a spectacular place to have people in their doonas, with bottles of wine and everything. The other thing is, they’re going to plan the track, then develop a business case for it. And after that, then do the environmental impact statement.”

WE HAVE, IN AUSTRALIA, BEEN FACING increasing inequality over recent decades. But not in the bush, not in our national parks, not in our wilderness. Out in those places, we could escape that. In the bush, we just were. In the bush, everyone was equal. But with these sales—because a lease of 60 years or more may as well be considered a sale—those days are no more. With parts of our public parks being sold to private interests, we will no longer be equal in them. And you needn’t be against soft beds and massages to be against choppers buzzing the sky or ATV tracks being carved through our parks, or for our wilderness being compromised, our wildlife threatened, our wild vistas ruined and park access being limited. And as each project gets approved, that only encourages more developments. There’s a buck to be made. And then another buck elsewhere. And elsewhere again.

Where does it end? Where does it end?

James McCormack is the Editor of Wild.

COMING UP: Part Two of this story here will look at what’s driving this process besides the obvious one—profit. The answers aren’t merely economic; there are deep philosophical issues at play. It will also address why the jobs argument touted by lodge backers is flawed, as is their argument of “athletic elitism”, and why there are differences between low-key public huts and the proposed private infrastructure. And it will look in more depth at what’s at stake: the loss of wilderness, the loss of challenge, the loss of equal access, and the loss of our lands.

A FEW SITES TO CHECK OUT:

Private Parks Not Public Playgrounds is a grassroots organisation on Kangaroo Island fighting the Flinders Chase NP development

Fishers And Walkers Against Helicopter Access Tasmania

– nqcc.org.au/save_our_national_parks

The North Queensland Conservation Council has been leading the fight against private lodge developments on Hinchinbrook Island

– npaq.org.au/current-issues/ecotourism-in-national-parks/

The National Parks Association of Queensland’s take on ecotourism

– tnpa.org.au/planning-matters/

Tasmanian National Parks Association has loads of link to planning and development issues within the state

– vnpa.org.au/hands-off-parks/

Victorian National Parks Association’s‘Hands Off Parks’ campaign

Footnotes

- To be clear, that’s not per person; it was for both of us to get use of the huts. But if you’re a sole adult with a kid, it’s still one person forking out $600.

- Actually, there’s another option. Although rarely publicised, you can do the Three Capes without staying in the lodges. In Wild’s Autumn 2021 issue, we’ll have track notes explaining how to do the walk for next to nothing.

- cg.tas.gov.au/home/investment_attraction/expressions_of_interest_in_tourism/eoi_tourism_projects

- Read Craig Pearce’s story about the SCT in Wild #177 Summer 2020 on p 68

- Actually the park’s Plan of Management states you can camp anywhere as long as it’s 200m from a formed track, road, picnic area, etc. But few are likely to search out and then wade 43 pages into the document to discover this when the website states you can only walk the track by booking online.