TEN CRUCIAL PIECES OF NATURE WRITING

Before you die, these all-time classics are must reads.

By Craig Pearce

(This story originally featured in Wild #174, Nov-Dec 2019)

My conscious journey into the realm of nature writing began relatively recently while swooning through Inga Simpson’s Understory, a heartbreaking and heart-fortifying memoir, viewed through the refracted incandescence of nature. In hindsight, however, the formative, and maybe most cataclysmic nature writing impact quaked into me many years ago, through the epic power of The Tree of Man and Voss.

The Tree of Man (like Voss, written by Patrick White; both being perspective-tilting literary thunderbolts) and Understory are alike in addressing a tension between nature and its harnessing for commerce, as well as the social dynamic which then unavoidably comes into play (Exhibits One and Two: Family life and community). It’s a frequently apparent theme in this selection of nature writing.

Having been brought up in country towns and, as [mis] fortune would have it, falling in with a farming crowd (by virtue of what-else-is-there-to-do-in-this-joint when we’re talking the pre-internet Golden Age of Growing Up and, well, a teenage boy can’t spend all his time playing sport, listening to punk and hunting girls can he), I inadvertently experienced first-hand the binary tropes of subjugating the land while simultaneously enjoying nature’s untamed dimensions through camping, wildlife encounters and Huck Finn living-by-the-river-type activities (Exhibit Three: Floating on tyre tubes down Tumut River with a rope-secured onion bag of beers. Note the safety rigour when securing vital resources).

Like any category of culture, nature writing’s borders are beautifully nebulous. Perhaps not everyone would include Voss, or Randolph Stow’s Tourmaline, as nature writing. For me, however, it’s instinctive, even though the control inherent within such categorisation is oppositional to nature’ amorphous sprawl.

In this piece, I call out nature literature that has not only profoundly moved me and opened my eyes to dendritic connections in the natural world, but is produced (I think!) by writers who passionately want what wilderness we have left—and even what semi-wilderness we have left—to be preserved, and if that means making it off-limits to all human beings, and/or significant chunks of us, so be it (Exhibits Four and Five: No helicopter landing pads in Tasmania’s Walls of Jerusalem National Park; and no huts or further duckboarding on its South Coast Track).

Just like when allowing nature to cast its primal spell over you through an intimate embrace (occurring most profoundly for me through extended exposure through immersions such as multi-day bushwalks (Exhibit Six), nature writing such as that featured here almost assertively forces you to slow down and to smell the lemon myrtle.

1. UNDERSTORY: A LIFE WITH TREES BY INGA SIMPSON (2017)

Understory is a prime, pellucid and compelling example of being wrapped in a physically overwhelming under-tow (yet so much kinder and forgiving than a ruthless riptide), and it is not long into its transfixing pages you recognise there’s something special occurring. This is one of those books (typical of excellent nature writing) where you meticulously savour each word, sentence and thought before reluctantly letting it go—like the view after a hard-claimed mountain ascent, wind chopping, everything in lurid focus.

Simpson’s personal life is one of many strands woven into an intimate (sometimes achingly so) narrative that includes her professional career, her background from a farm in central west NSW, protecting and strengthening nature’s hold on Earth, and an exploration of nature writing itself. This latter leitmotif was for me an epiphanic explosion. Since languidly breaststroking my way through its pages, I have read many of Simpson’s totems, including A Million Wild Acres. It sent me off on an exploration—literary in this case—comparable to those I have undertaken in the wild (and often as exciting and satisfying).

While Understory—like The Tree of Man, A Million Wild Acres and The Bush—is an unmistakably Australian work of art in character and milieu, it resonates with a booming, crystalline clarity across all cultures and the ways in which we contend with nature. To write a book like this, you can’t fake it – Simpson’s writing glows with compassion.

2. THE OLD WAYS – A JOURNEY ON FOOT BY ROBERT MACFARLANE (2013)

It’s hard to stay away from hyperbole—I seem constantly on the precipice of no-return-from-this-gaping-abyss with nature writing that affects me— when describing Old Ways and Macfarlane’s writing in general. Bottom line: get to this book quickly, then venture through it slowly. If you are an acolyte of luxurious narratives about being subsumed by the outdoors, of going on journeys—by foot, by boat—whether inland or on the littoral (all Macfarlane’s writing is on the edge of something, be it vocabulary, nature’s attenuation, the foregoing of lives and lifestyles), then Old Ways will be your tender friend.

Entwined in this book’s narrative, and one of the engines providing its muscular propulsion, is a connectivity between the journeys and their cultural and social associations. The routes that Macfarlane takes sometimes seem to exist in barely more than folk tales and rumours. This romantic dimension is reinforced by the knowledge that in a land as worn (out?) as Britain, there are still sanctuaries of what we might call wild areas (if perhaps not quite wilderness), even if the distant roar of a jet engine sometimes intrudes on them.

Macfarlane’s language is a signature attraction, or barrier, depending on your literary starting line. More than any other nature book I’ve read—perhaps with the exception of one of Macfarlane’s pivotal influences, The Peregrine—do the words and their conjugations offer a startling, take-your-breath-away phenomena—a grammatical Aurora Borealis. They cut incisively to the quick while levitating with imaginative majesty.

3. THE BUSH BY DON WATSON (2016)

Watson lives large in my pantheon of Australian heroes because he was Prime Minister Keating’s longstanding speechwriter. He helped Keating galvanise sentiments and ambitions into executed outcomes (such is the power and influence of language on reality). The pair, along with others like PM Hawke, were the most recent Australian Federal Government cadre who executed achievements of substance as a habit, rather than as exceptions.

Politics has not ebbed from Watson’s veins. Here, the bush reverberates with political power and ramifications. In erudite, elegant terms Watson explains how Australians, “would not be who they are—and would not know themselves—if they had not fought the war with nature.” Nature enslaved, then.

And yet, despite this and despite most Australians living separate from the bush, it exerts a compulsion on our psyche that is culturally defining. The bush, writes Watson, is both “real and imaginary…in that the life it harbours is that of the Australian mind…it is the source of the nation’s idea of itself.”

Beginning from Gippsland in eastern Victoria, where he was brought up, Watson goes semi-swagman fully peripatetic across Australia, recounting fact and anecdote in a dazzling, mellifluous constellation of observation and analysis.

You can smell the rain coming; the freshly ploughed earth; the evocative stench of cattle bustling their way into a milking shed on a freezing morning; the dry hay in its bales as it is lifted and thrown onto the bed of a truck. You can just about drown in the book’s sensual surfeit.

Watson is fiercely poetic and encyclopaedic. He presses the heart when describing the terrific power nature exerts when it is left virgin, unsullied by humanity’s soiled, avaricious grasp. A disquiet, a bitterness and, yes, a disgust that so little of it—comparatively—remains lies volcanic under the prose.

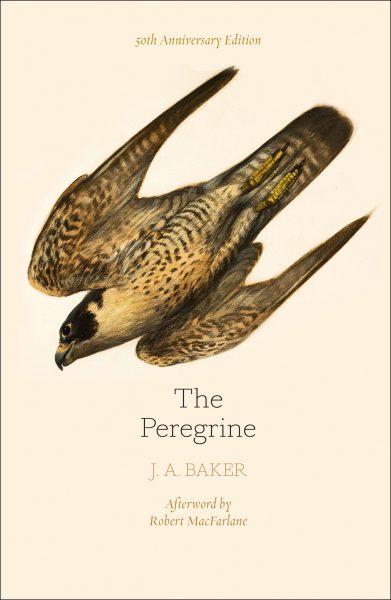

4. THE PEREGRINE BY J.A BAKER (1967)

Like a prehistoric wasp caught in amber, this adamantine, spiritual beacon for all nature writers and everything the genre aspires to is a perfect relic, carrying with it—however—a relevance and resonance for right here and right now and for aeons to come. Almost the only thing written by Baker—set in Essex, England in the early sixties over a putative winter—it pursues, investigates and, in an unfathomably empathetic way, lives what peregrines—falcons that kill without mercy and kill often—live.

Applying language with diamond-edged precision, turning nouns into verbs, verbs into nouns and manifesting like a delirious swirl of hypnotic poetry, this book teleports you into the heart of a wildly wild creature—a brutal knight of nature (and at over 320km per hour, its fastest too).

An early piece of environmental activism (though such is its modesty you barely notice), there is a positive piece of rare environmental serendipity as peregrines—which were dying out at the time of the book’s writing—have since made a startling comeback due to the chemicals then used in farming, which were impacting peregrine numbers, being ‘retired’. Yet their struggle for security continues, as more recently pigeon fanciers and game shooters have become their persecutors.

5. A MILLION WILD ACRES BY ERIC ROLLS (1981)

6. WALDEN BY HENRY THOREAU (1854)

While including Walden on this list is perhaps predictable, this 1854 classic makes the cut for three key reasons: Firstly, it was pioneering in its recognition of the power and value of nature. Secondly, because of the quality of its storytelling, including the quirks which come, partly, as a result of its vintage but also from Thoreau’s humour and pernickety mindset. And thirdly, because of its propensity to provide such rich pleasure.

The virtual diary that is Walden overflows with such a bursting-bud-like love of being outdoors, of synchronicity with nature, that it seems curmudgeonly not to join in his joy and, like him, sip from the revitalising pleasures of living fully in nature—taking from it what is needed, but no more, and treading lightly on it. No one writing or reading about nature can consider themselves satisfactorily educated without taking a languorous stroll (bathing in its contemplations and homilies) through this glade.

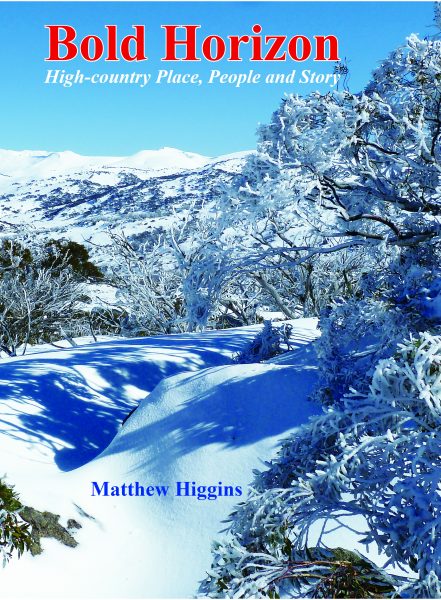

7. BOLD HORIZON BY MATTHEW HIGGINS (2018)

Higgins excels in documenting and discussing people two of Australia’s great alpine national parks: the ACT’s Namadgi and NSW’s Kosciuszko. While the geography and its climate are leading lights in his books (Rugged Beyond Imagination is another excellent example), it’s the people of this wild country who live largest of all. Their spirit, adventurousness, tolerance of hardship and wry, warm wit thrives through Higgins’ enthralling narratives.

He talks of nature, of man transforming nature into a different form of ‘cultivation’ and the social, commercial and historical constructs that eventuated from their efforts—roughly speaking from the mid-19th to late 20th century.

It’s astonishing how much territory Higgins covers, especially given its assiduously captured detail. Yet he does so in an organic, flowing manner that, despite or because of its factual basis, is at its heart is simply great storytelling.

8. IN SEARCH OF SPACE BY ROSS BROWNSCOMBE (2017)

Brownescombe’s constant pursuit of space encompasses air, solitude, and nature’s raw, idiosyncratic beauty. He has a predilection towards colder climes (Exhibits Thirteen, Fourteen and Fifteen: Alaska, Tasmania, and Norway), yet while his prose is spare and stealthy like that of a big cat on the hunt, within it is a furnace of warmth.

A self-confessed itinerant of the wilderness, Brownescombe’s journeys by foot and by vessel describe both the environment and his travels/travails/enlightenments in those environments in limpid, placid and patient prose. It is not complicated, but it is very, very real—a beautiful, haunting primeval grasping of life out of doors. He inspired me to take the Louisa Beach diversion on Tasmania’s South Coast Track (which I did not regret!).

9. H IS FOR HAWK BY HELEN MACDONALD (2015)

All the titles included in this top ten are works of literature, but H is for Hawk is perhaps the greatest all-around work of literary art featured. Weaving together the strands of training a hawk and how doing so helps console McDonald as she grieves the loss of her father, it is innovative in structure and captivating in its leveraging of language. The hawk takes on human, and even God-like characteristics for McDonald. Of greater impact on her healing, however, is the hawk’s wildness. The book’s fiery, draining vortexes of nuclear emotions and typhoon cameos of descriptiveness pulse violently through its veins…elemental, coruscating and pure.

10. UNO’S GARDEN BY GRAEME BASE (2006)

You think I’m joking? When I was the parent of an under five, this was my favourite book of all-time to read (and believe me, when you read to under-five creatures you tend to do the same books time and time again, so they need to be good!). Synopsis: Nature; nature discovered; nature colonised by humans; humans poison / destroy nature; humans leave poisoned city (now formerly-nature); nature recovers, and humans return to live in harmony with nature. Uno’s features amazing creatures and flora, the lovely environmentalist Uno, and the coolest illustrations ever. Pure genius.

CONTRIBUTOR: Sydney-based Craig Pearce began his writing trek at the trackhead of rock’n’roll, veered through the corporate world’s twisted trails, and now navigates the serene great outdoors.