How long have you been mapmaking for, both for yourself and professionally?

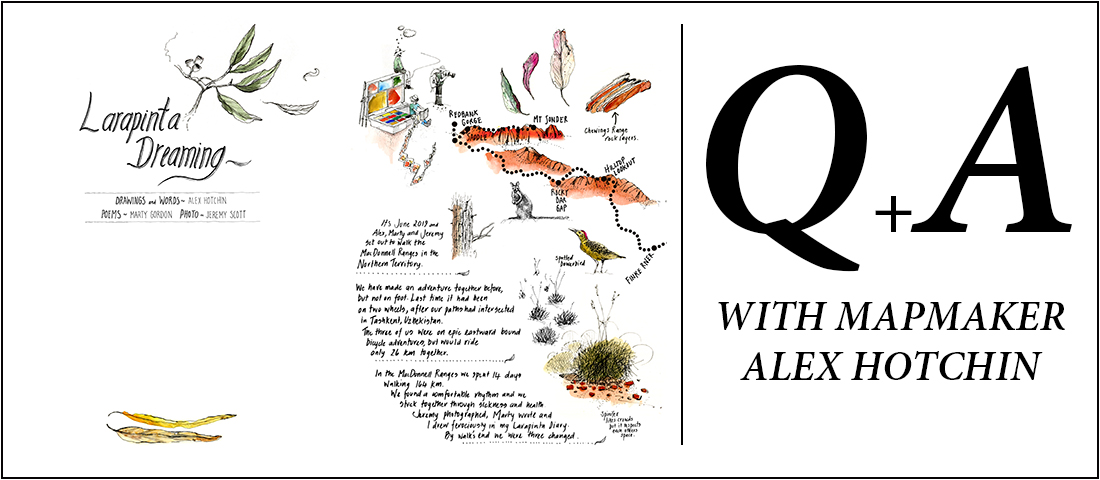

I have always drawn a lot but started making maps personally in 2014, after returning home from an 18-month overland bicycle journey from Scotland to Cambodia. It began with making some personal maps of that bike adventure and has grown to become what I now do professionally.

Your maps clearly display your talents as an artist. But what drew you to mapmaking to express those talents?

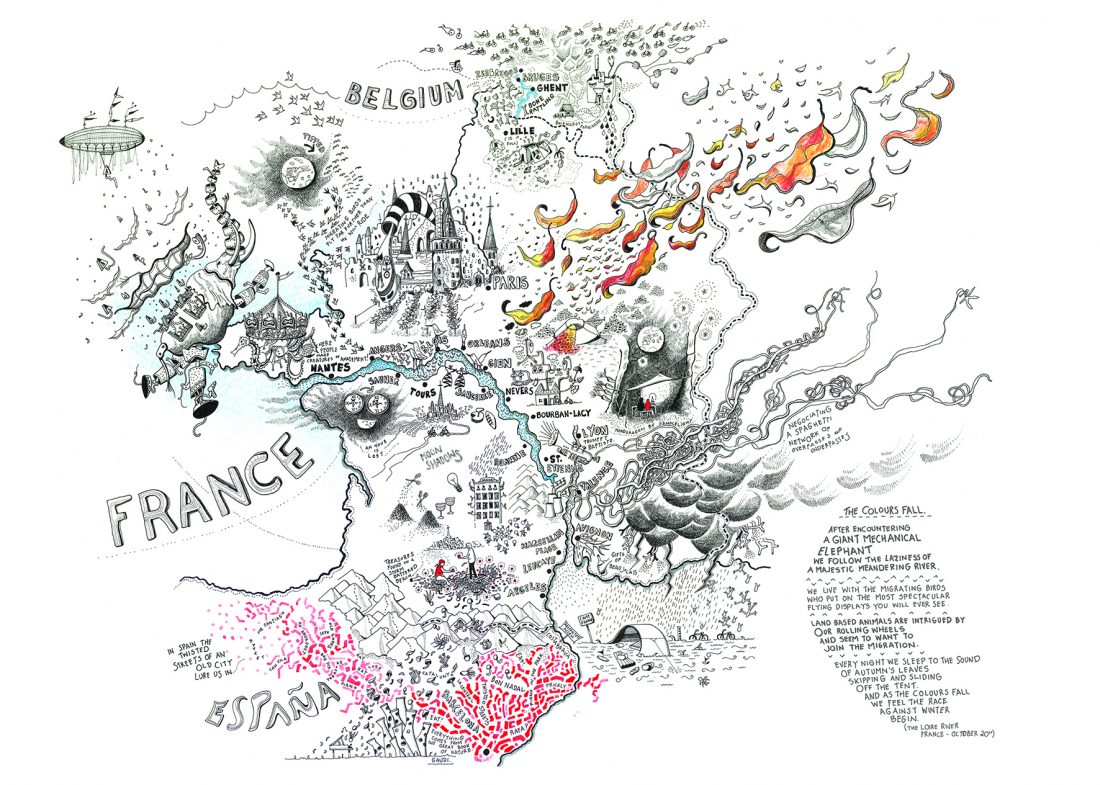

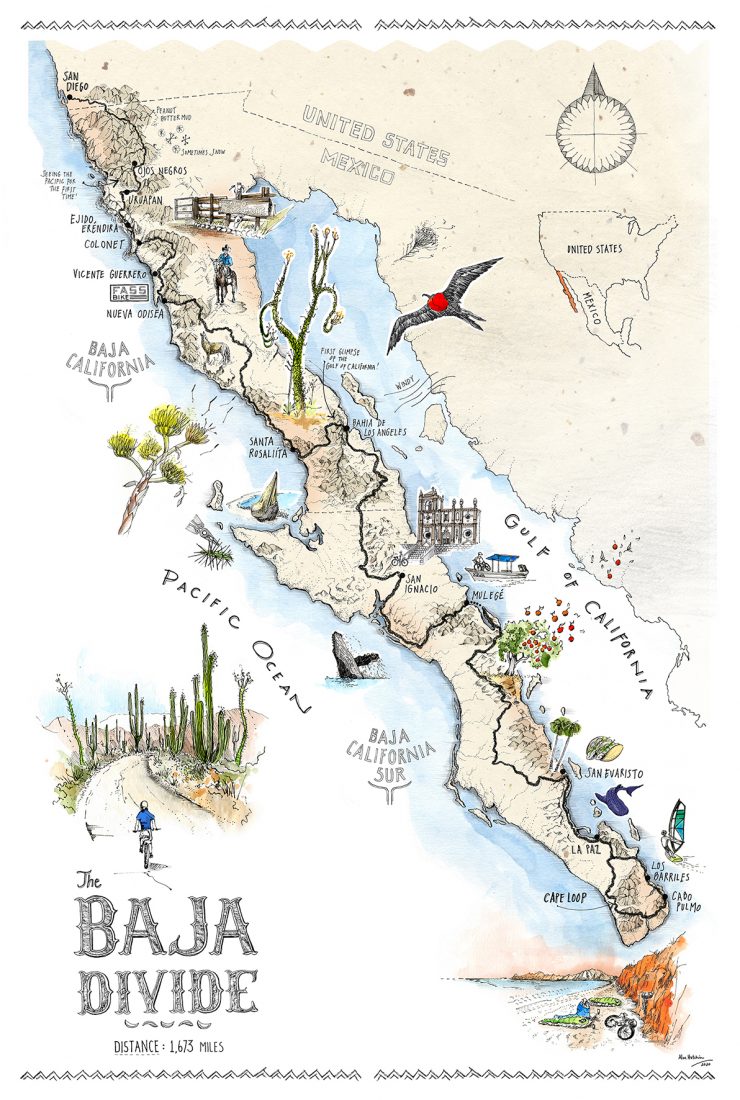

When I went on my bicycle journey, I decided I didn’t want to take a phone or GPS and wanted to navigate by paper maps. I loved the challenge of finding my way using the contours and landmarks. I got lost a lot but there was great reward in asking people directions – and interpreting their responses. The beauty in being lost is you gain interactions with others and the experience of being thrust into the unknown and all that comes with that. When I returned from my trip I realised that my words and photos could not explain what I had actually experienced so I set out to draw it. It seemed natural that the artwork becomes a series of maps with notes and drawings overlaid, as it was a journey from one place to another.

What is it about ‘place’ that attracts you?

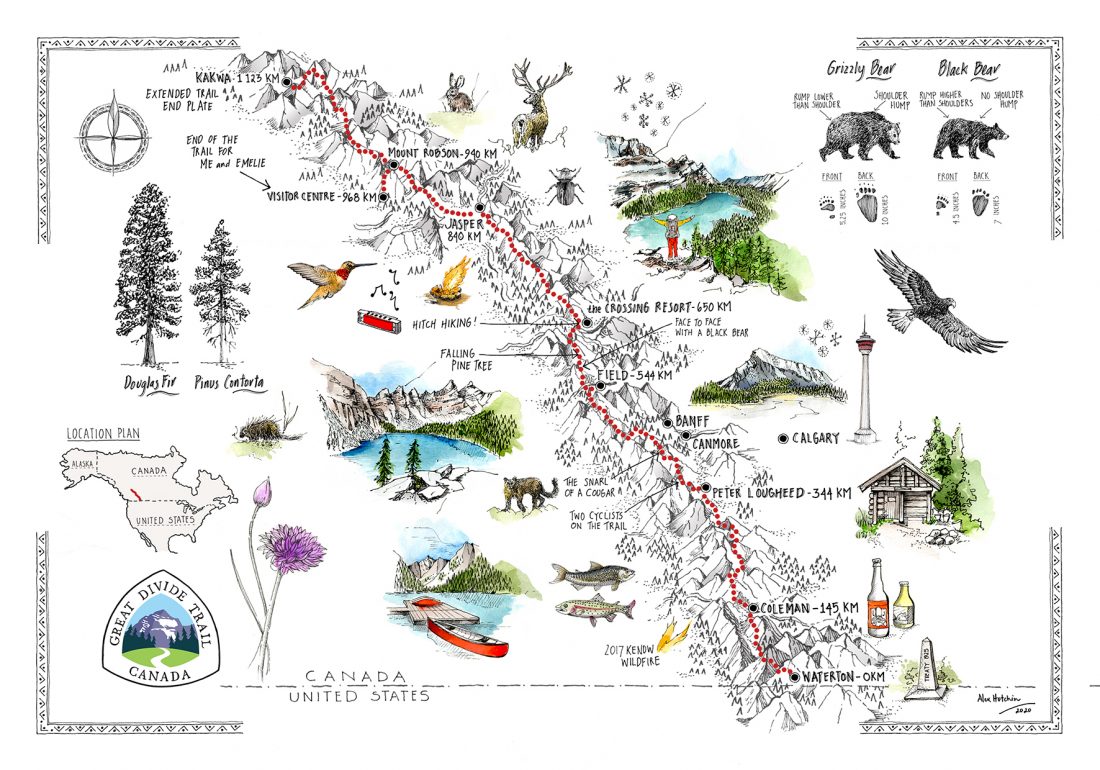

The idea that for every place there are multi layered stories to be told. I’m inspired by David George Haskell’s “The Songs of Trees” where he talks about what he discovered by returning to the same one metre patch of forest for a year, and the drama that he witnessed playing out in that very small area. I am interested in all of the little details that make up the story of a place.

When I think back to maps created centuries ago—say, with medieval maps where alongside land masses there sat drawings of ships, monsters, fabled creatures and so on—it seems that illustrations and explanatory, often detailed annotations were far more integral to mapmaking than now. Why was that relationship lost? And at what cost?

There once existed a mysterious world full of unexplored places and unknown lands. Humans filled their imaginations with the storytelling of these places inhabited by monsters and myths and believed in something larger than themselves. In our modern lives we place ourselves at the centre of our world, and now mostly use electronic devices to find the way to where we are going. I appreciate the convenience of GPS technology, but it means we learn less now about the intricacies of the journey in getting somewhere. There has been a loss in geographical literacy.

The annotations you provide for maps can be incredibly poetic. Why do you think beautiful words are incorporated to so few maps nowadays when they can add so much to their power?

Often my words are momentary thoughts or questions – a way to have a conversation with the world around me. Maps can be a conversation or an expression of possibility rather than a finite work. I’m not sure why so few maps include words – perhaps because the majority of map-making is now done digitally and notes lend themselves more towards hand-drawn maps.

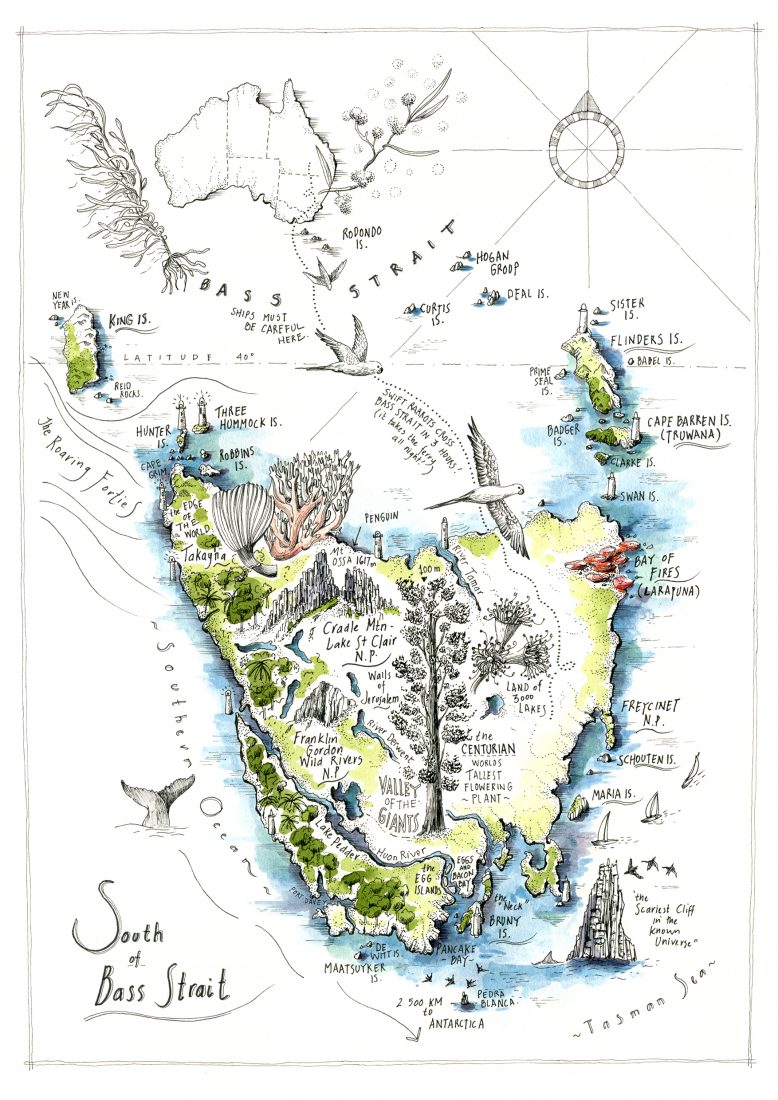

The map you recently did for Wild was not merely a graphical representation of place, as most maps are; it was simultaneously a representation of time and narrative. What advantages do you think map-making has of conveying a story over a traditionally-structured magazine story using words and photos? And on a personal level, does sketching your way through a landscape provide a radically different experience to someone who’s photographing and writing about it?

There is beauty in both. To me, a storytelling map conveys the experience of an adventure as you pick your way along the drawing – like you would if you were walking this track yourself. I use my artwork to show the possibilities but not reveal everything – I’m inviting the viewer to go and see for themselves.

Taking the time to draw and record a landscape feels to me like honouring the conversation I have with it. It’s a respectful process, and something I need to do to get to know where I am. In my experience, it is different to photographing, which is often about searching for the spectacular image. I believe drawing is a more modest pastime.

Can you talk a little about the processes you go through to create a map?

It starts with lots of research. Sometimes this will involve referring to my own journals, or listening to the stories of others. It will be different depending on the type of map, and whether I am working on a personal or commissioned project. The drawing itself starts with the topography – and often I will refer to google earth for this, or paper maps and atlases that I have collected. The stories and anecdotes are added last. I do make original work, but most often my maps are hand-drawn and scanned to create layered electronic files that can be adjusted and resized for varying uses.

Do you also do any traditional cartography, or is your work solely illustrative?

At this stage just illustrative, because I am not skilled enough for the traditional cartography type.

What’s been the most unusual map you’ve been asked to create? And what’s been the most challenging?

They would both be the same map – a small map for a publication about the Thai cave rescue. Unusual because it is a map of an underground part of the world and challenging because no maps actually existed to reference – it was made entirely from a verbal brief.

To see more of Alex’s impressive work (and maybe even to purchase some of it, including the Larapinta Dreaming map that ran in Wild), go to alexhotchin.com