By Warwick Sprawson

In January 1910 an Austrian-born man with a luxuriant black moustache and his Tasmania-born wife climbed Tasmania’s Cradle Mountain.

As they gazed out over Cradle Valley’s pristine lakes, glacier-carved valleys, buttongrass moorlands and mossy rainforests – all chock full of species found nowhere else on earth – they looked at each other and made a vow. This area – at the time only known to a few hardy hunters, trappers and mountaineers – needed to be protected from the encroaching threats of mining and logging. It needed to be preserved for all people for all time.

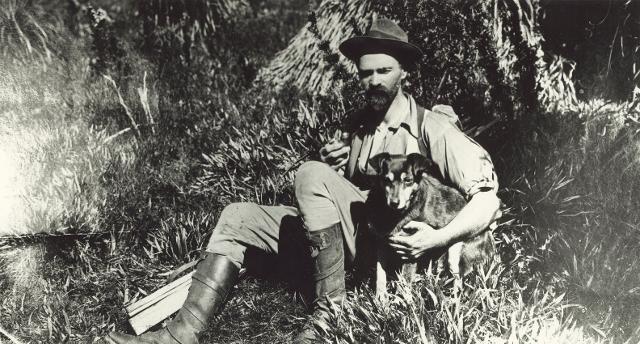

Gustav Weindorfer had arrived in Australia in 1900, aged 26, leaving behind a tedious accounting job in Vienna for adventure in a new country. With a keen interest in the natural world, he soon started exploring the bush around Melbourne as an energetic member of the Victorian Field Naturalists Club. At the club he met his future wife, Kate Cowle – 11 years his senior, and began visiting her and her sister at home, helping them classify their wildflower collections and singing Austrian folk songs to Kate’s piano accompaniment.

Gustav was tall, strong and engaging, with a thick accent and an even thicker handlebar moustache. Kate was exuberant and musical, with full lips and lively brown eyes. Both Gustav and Kate were passionate about using scientific observation to unlock the mysteries of the natural world, and enjoyed nothing more than a botanical ramble, rain, hail or shine.

At the end of 1905 Kate and Gustav moved to Kindred in northern Tasmania where Kate had been born. On 31 January 1906, the day before their wedding, Gustav and his future relatives fought a bushfire threatening the Cowle family farm, succeeding in saving the homestead in which he and Kate were married – still smelling of smoke – the next day.

Their honeymoon was five blissful weeks in a leaky tent on nearby Mt Roland collecting plant specimens and subsisting on kangaroo tail soup. Gustav was impressed by Tasmania’s rugged scenery, which reminded him of his mountainous homeland. For the first time, far in the distance, he saw the distinctive scooped ridge of Cradle Mountain – and his curiosity was piqued.

After the honeymoon they bought a cottage and 100 acres of farmland in Kindred, naming it Roland Lea. They ran dairy cows, planted walnut and cherry trees, and established a large vegetable garden.

Almost four years after their wedding, Kate, Gustav and friend Ron Smith – a local farmer and fellow adventurer – finally got the chance to leave their farms and head southwest across trackless moorland to climb Cradle Mountain. Kate was the first woman ever recorded to have climbed the mountain. All three were awe-struck by the beauty of the area.

Kate and Gustav’s vow to protect Cradle Mountain and the surrounding area was not idle talk. In December 1902 they had stayed at Mt Buffalo National Park in the Victorian Alps and learned firsthand how the construction of basic bushwalker lodgings had led to the arrival of visitors, then to a road, then to more visitors and finally to the declaration of a national park – one of the first in Australia. If it could be done in Victoria, it could be done in Tasmania.

The day after climbing Cradle Mountain for the first time, Gustav, Kate and Ron scouted Cradle Valley for a place to build a lodge, finding the perfect location at the edge of ancient pine and myrtle forest beside a clear flowing creek. Kate and Gustav purchased 400 acres of land on the site.

With Kate looking after the farm in Kindred, Gustav returned to Cradle Valley in early 1912 to start building the lodge, fashioning a rough three-room structure using only fallen King Billy pine and the most basic of hand tools. Gustav called his construction Waldheim, Forest Home in his native tongue, and carved a motto on the wall near the fireplace, ‘This is Waldheim, where there is no time and nothing matters.’

By December 1912 Kate and Gustav were ready to welcome their first visitors to the lodge – Ron Smith and his wife, Kathleen Carruthers. The accommodation was far from luxurious, with bunks of split timber and hessian, mattresses stuffed with sphagnum moss and logs for chairs. Just accessing the lodge was an adventure; the tracks were so bad that horse and cart deliveries had to halt 14km away.

Kate returned to Kindred to run the farm, earning the money needed to finish the lodge. Once Waldheim was completed the plan was that Kate and Gustav would live there, jointly hosting adventurous travellers, showing them the area’s wonders and expounding on the need for a national park.

Gustav was kept frantically busy working on Waldheim for most of 1913, expanding it to eight rooms, spending weeks – or even months – away from Kate. Although separated, they exchanged long, vivid letters every day, describing every absurdity, triumph or setback.

January 1914 saw their first paying visitors to Waldheim. Gustav was in his element, hosting guests, guiding, cooking, and enthusing on the area’s flora and fauna. Kate was prevented from coming to Waldheim by reoccurring chest pains, remaining on the farm until her health recovered enough to join Gustav in June.

Bookings for the 1915–1916 summer season were even busier, including Evelyn Temple Emmett, a keen bushwalker and the director of the Tasmanian Government Tourist Bureau. Evelyn was almost enthusiastic about the wonders of Cradle Mountain as Gustav himself, and on his return to Hobart spruiked the charms of the area to newspapers and proposed that the Scenery Preservation Board protect 35,000 acres of the Cradle area.

But just as their dream seemed to be coming into fruition, Kate’s heart complaint returned. Gustav, torn between hosting duties at Waldheim and caring for his sick wife, cycled 80km to the hospital in Ulverstone every day for four weeks, distracting Kate from her pain with the latest stories from the valley.

Kate died on 26 April 1916, aged 53, likely from undiagnosed cancer. Gustav wrote in his diary, ‘I have lost my best friend’.

The following years were bleak for Gustav. He mourned his wife, her absence heightened by long periods spent alone at Waldheim.

Since Australia had joined the First World War in August 1914 anti-German feelings had grown as the war dragged on and more and more Australians were killed. Local sentiment turned against the Austrian ‘hermit’ in the mountains, with many suspecting Gustav, with his thick accent, and strange love of garlic and coffee, was a pro-German spy. Waldheim was raided and searched by the authorities and Gustav’s mail read by censors. To counter these suspicions, Gustav tried to enlist in the army in 1917, but – at 44-years-old, was rejected.

Just as bad, Gustav and Kate’s proposal to protect the Cradle Mountain area was dropped during the immediacy of the war. Lonely and despondent, Gustav fell into a deep depression.

At the nadir of his woes in early 1921, with no money and no visitors to Waldheim, Gustav was tempted to sell the timber on his plot in Cradle Valley. Only a collapse in timber prices saved him from a mistake he would have always regretted.

With the value of timber low, Evelyn, the director of the Tasmanian Government Tourist Bureau, saw the chance to relaunch the campaign to preserve Cradle Mountain, concentrating on tourism’s potential to create jobs. Gustav, jolted from his lethargy, joined the campaign, conducting newspaper interviews, lobbying ministers and government agencies, and building public support through public lantern-slide lectures.

Finally, on 16 May 1922, 64,000 hectares from Cradle Mountain to Lake St Clair were declared a ‘scenic reserve and wildlife sanctuary’. For Gustav, it was a bittersweet moment, as Kate was not there to share the triumph.

The following years saw interest in Cradle Mountain and Waldheim rebound. Gustav regained some of his former zest, guiding hikes, cooking his famous wombat stew, playing cards and regaling his guests with tales of old Vienna. He also turned to letters for companionship, corresponding with scientists and naturalists from around the world, contributing to scientific papers and supplying rare specimens for study. He kept meticulous daily records of Cradle Valley’s temperature, rainfall, humidity and sunlight.

As visitor numbers grew, local trappers also began to lead walkers into the mountains, guests sleeping in the basic trapper huts dotted across the region.

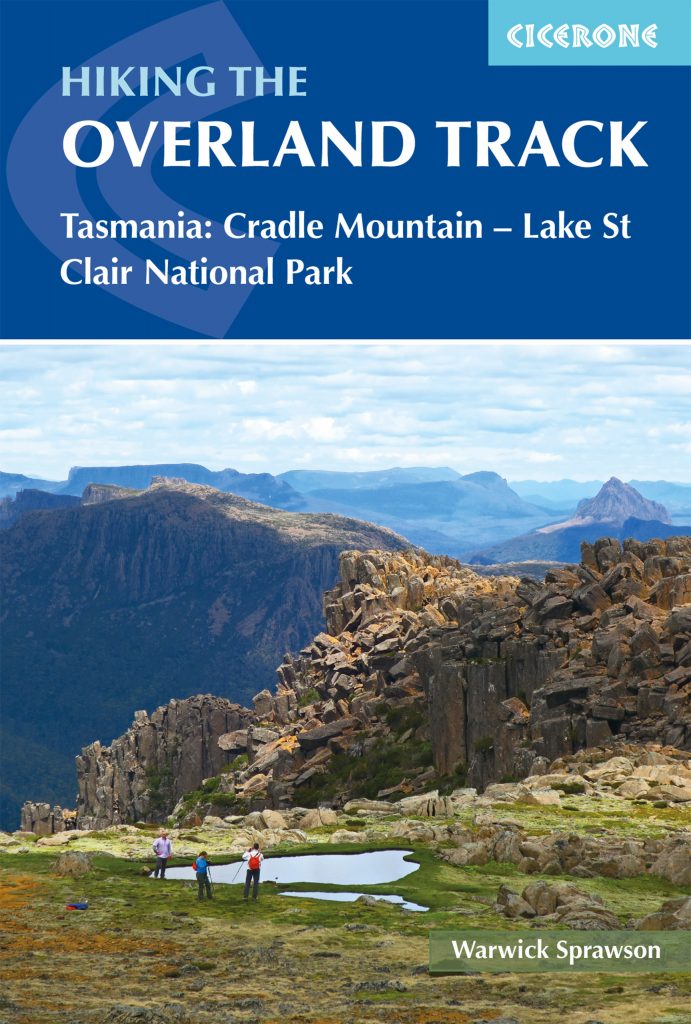

In 1930 the board overseeing the scenic reserve employed the former trapper Bert Nichols to blaze a track from Cradle Mountain to Cynthia Bay on the southern shore of Lake St Clair. After blazing the track, Bert wrote to Evelyn, cheekily inviting him to try out the new trail. Evelyn took Bert up on his offer and, with a group of seven friends from the Hobart Bushwalking Club, completed the track in the summer of 1931 – the first hikers to walk the Overland Track.

In May 1932, aged 58, Gustav was trying to kickstart his recalcitrant Indian Scout motorbike when he had a heart attack, collapsing dead beside his forest home. His friends gathered to mourn, burying him in front of his beloved Waldheim.

After Gustav’s death, his sister sent everlasting flowers and candles from Austria, requesting that they are placed on his grave, as was the custom in his homeland. This tradition continues today, with a simple commemoration service held each year to thank Gustav and Kate for their vision – the Cradle Mountain – Lake St Clair National Park, a reserve which now enjoys World Heritage status. The 88th annual memorial will be held 3 May 2020.

Warwick Sprawson is a keen writer and hiker. Cicerone has recently published his guidebook to the Overland Track, see www.woodslane.com.au.

For further information on Kate and Gustav’s story see Kate Legge’s Kindred – A cradle mountain love story.