By James McCormack

In the end, it came down to one envelope and one helluva lot of luck. The saving of the Franklin River, the greatest environmental battle in Australian history—a battle that saw political leaders deposed, states’ rights defined, tens of thousands of people mobilised, more than thousand arrests, and eventually, resulted in the saving of Tasmania’s greatest wild river—arguably came down to luck and a single rarely discussed act: a staffer sending on a letter from an ex-premier before his successor had a chance to destroy it. Without that letter being sent, the Franklin may well be flooded today.

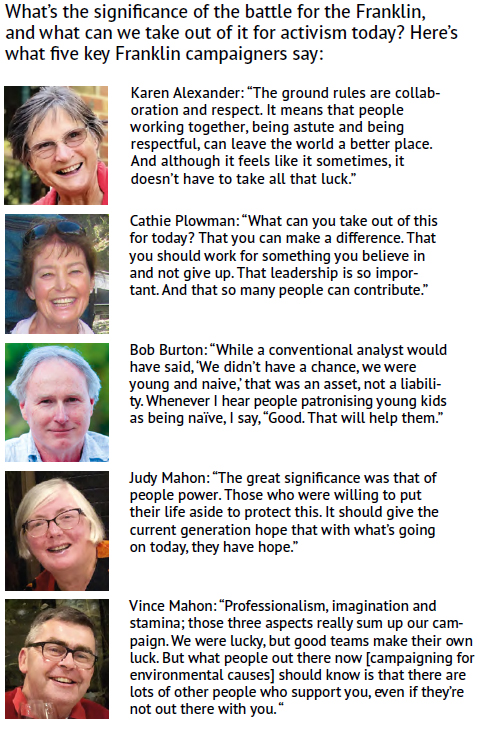

Of course, there was far more to it than that. In the scheme of things, the letter might seem trivial when compared to the seven years of campaigning and to the fact that people gave up jobs, moved interstate and put their lives on hold. And of course, it involved far more than one person, even if that one person is Bob Brown. More than anyone seen as the face of the campaign, Brown says he is sometimes introduced as, “The man who saved the Franklin. I have to get up and say, I’m sorry but that’s not true. I can name at least half a dozen other people without who, had they not been involved, the Franklin would have been lost.”

In retrospect, it seems hard to believe saving the Franklin was even a close-run thing. Nonetheless, history records it came down to a single vote in the High Court. But before we start, you have to understand the power of Tasmania’s Hydro Electric Commission, the quasi-governmental authority charged with generating hydroelectricity, along with constructing the necessary dams to do so. Back in the 70s, the Hydro, as it was known, was Tasmania’s largest employer, this in a state with the country’s highest unemployment. And to many Tasmanians, the Hydro was also symbolic: it meant progress. It was powerful, too. It’s said that when big businesses came to Tasmania, they met the Hydro first before visiting the government. Even Doug Lowe, state premier during much of the campaign, said that when he was castigated after giving his first speech to parliament—he spoke about reviewing the decision to flood Lake Pedder—it occurred to him that it wasn’t the government controlling this issue, it was the Hydro.

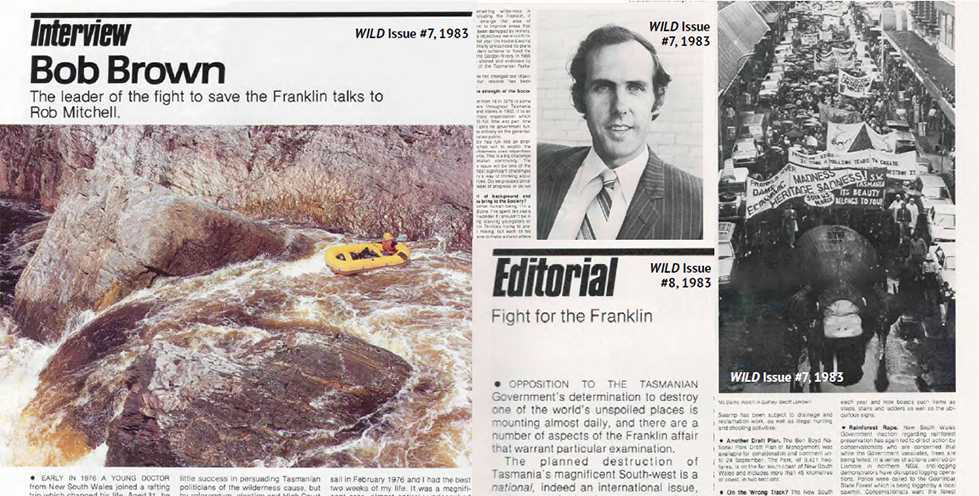

By 1970, more than 40 dams had been built across the state. Only one major river still ran wild and free: the mighty Franklin. First descended in the 50s (see John Dean’s profile on p34), the river remained the preserve of canoeists and kayakers until 1976, when Paul Smith asked around to see if others wanted to join him on the first ever rafting trip down it; only Dr Bob Brown, a GP from Liffey in northern Tasmania who had no prior rafting experience, decided to come along.

It was a magical trip. They struck two weeks of fine, gorgeous weather. The river was low, so they could take their time. “We paddled down this beautiful river,” says Bob Brown, “with waterfalls coming in from the side, with sea eagles soaring and platypuses in the river, the leatherwood petals floating downstream.”

The Hydro had, at that stage, not announced they were damming the Franklin. They didn’t end up seeking approval to dam the Gordon River, which would in turn flood the Franklin, until 1979. But it was already clear what their intentions were. Frenchman’s Cap, at the heart of the Tasmanian wilderness, would be surrounded by a series of still, dead lakes. One of the world’s great wild areas was on the line.

Appalled, Bob Brown had a meeting at his place in Liffey. Including himself, 16 were there. Some of those attending had descended other southwest rivers, like the Jane or the Gordon. And they had varying degrees of experience within the conservation movement. Some—like Helen Gee, and Bob and Stuart Graham—had been involved in the unsuccessful campaign to save Lake Pedder, inundated by the Hydro back in 1972; others had never been involved in the conservation movement at all. Before that night, Bob Brown had no background in environmental activism. “None,” says Brown. “Zero. Zilch.”

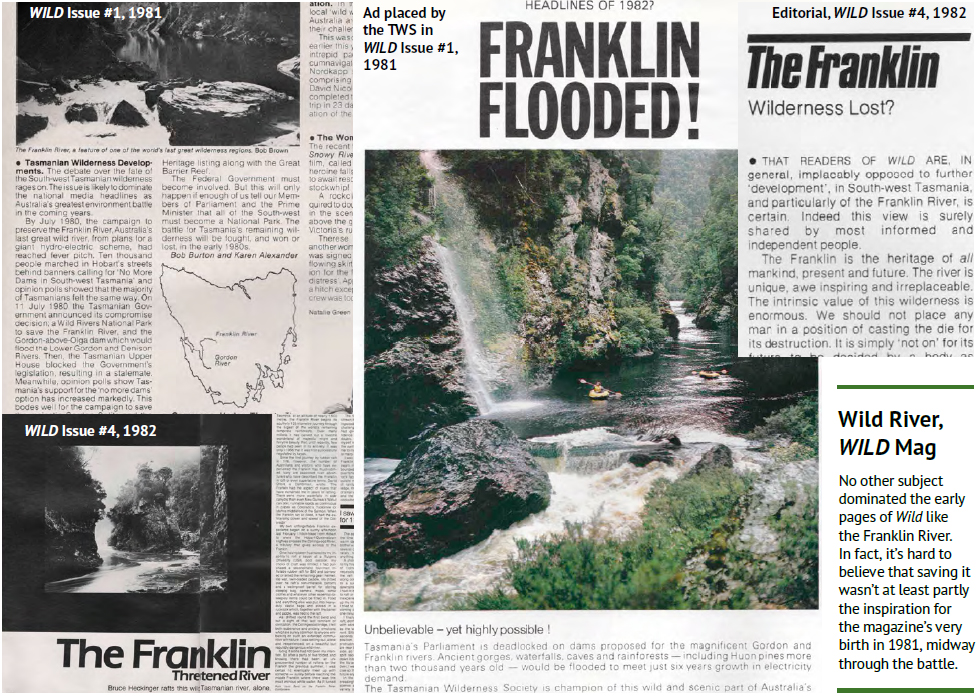

It was clear, after the loss of Pedder, that if damming the Franklin was to be stopped, opposition to it had to start early, so that very night, at Brown’s place, the group formed the Tasmanian Wilderness Society with Kevin Keirnan as its director. It was also clear they had to let people know how special the Franklin was. They began organising meetings and slide shows, and, critically, they used the media. In the early days, they took out a double-page ad in the Examiner. Later on, they ran a series of full-page ads in the Wild’s first ever issues (see above). Smith and Brown also decided they should paddle the Franklin again in 1977, and after making a movie of the trip together with Rick Rolls, Peter Thompson and Sam (Amanda) Stark, they paid $800 to get it shown on Tasmania’s commercial stations. In 1980, Brown along with directors Chris Noone, Stacey Gavrily and Michael Cordell, released another movie: The Franklin: Wild River.

There were also a couple of fortuitously-timed technological advances that helped greatly with getting the Franklin better known. The first was the advent of colour TV. “It had a huge impact,” says Brown. “As opposed to black-and-white when Pedder was being fought for, [colour] meant people could relate to the Franklin. [It] meant people were willing to blockade the river.” The use of colour extended to print media, which at that time was not widespread. Those full page in Wild’s early issues are a case in point. While much of Wild back then was still black and white, the ad was full colour. The TWS, too, began producing a colour magazine. And widespread colour reproduction of Peter Dombrovskis’ famous Island Bend photo (seen in the ad on the following page) captured Australia’s imagination.

The second luckily-timed advance was one that’s rarely credited but was utterly influential in saving the Franklin: rubber rafts. Without them, the Franklin—with its churning rapids and thunderous whitewater—would have remained the preserve of kayakers and canoeists with considerable expertise. Thanks to rafts, however, the Franklin became accessible to people with no prior paddling experience.

For many who became deeply involved with the campaign, rafting provided the initial inspiration. Bob Brown was a prime example. But he wasn’t alone. Some, like Sydney’s Ian Cantle, rafted the Franklin and promptly dropped out of uni to assist with the campaign. Bob Burton, who rafted it with Cantle—and who, like Brown, had no prior paddling experience—finished his degree but then moved to Tasmania in 1979 to help once he’d graduated. Geoff Law was yet another inexperienced paddler whose rafting trip led to him becoming an integral part of the campaign. Not everyone could move to Tasmania, of course. Ben Lans, for instance—a Queenslander initially inspired to raft the Franklin after seeing Wild River—stayed in his home state after paddling the river but nonetheless joined Queensland’s branch of the Tasmanian Wilderness Society and became its president.

Recognising the inspirational power of rafting, the TWS began organising trips down the river. They took members of the media down it, most notably from Melbourne’s The Age newspaper, which soon published influential editorials defending the Franklin. Rafts also allowed them to take federal politicians down, an act guaranteeing media coverage. But more generally, the TWS also knew that the more that rafted—and were thus inspired by—the river the better. As Bob Brown says, “We’d been down the river, and we knew what was to be lost. Almost none of our opponents had been.” To that end, the TWS published rafting notes to let others discover it for themselves, and when the society set up a shop in Hobart to help raise funds, it even sold rafts.

There was another aspect to rafting. Tasmania’s canoeing and kayaking fraternity was, says Bob Burton, “largely apolitical, or didn’t want to criticise the Hydro because they controlled [the river flows]. It meant political advocacy from paddlers was limited.” But rafting let bushwalkers run the Franklin, and within Australia’s bushwalking community, says Burton, there was a tradition of advocacy. Burton himself was a case in point, a walker who’d fought for environmental causes. So, too, was another Sydneysider Vince Mahon. He’d lobbied Neville Wran’s government to save the northern NSW rainforests, and after coming down to visit Burton, he ended up staying on, working full time on the campaign from 1980 to ’83.

Other bushwalkers joined. Melbourne’s Karen Alexander had walked in Tassie’s southwest; it was, she felt, her “spiritual home.” And like many others who got involved, she’d never got over the drowning of Pedder. “I was angry,” she says. “When the Franklin came around, I didn’t even need to think about it.” And Cathie Plowman, a Sydney nurse, first walked in Tasmania in 1979. When she heard about the referendum, she packed her bags and came down. But the first she actually got to see the Franklin was when she rafted it last year. It was always just enough to know it was there.

But while the outdoors inspired many, it was apparent the campaign had to go beyond bushwalking circles; the general public had to care about the Franklin. It was also clear the campaign had to be taken nationally. “We couldn’t win it just in Tasmania,” says Brown. “The Hydro had such power that both big parties [Liberal and Labor] would lock in behind it. And so would the media. And the unions. And the chamber of commerce.”

Karen Alexander was a key driver here. She stayed at the TWS’s Melbourne branch (for a while its only full-timer), and began organising national strategies, something the Tasmanians were less focussed on. “But it’s understandable,” says Alexander, “because with [Premier] Doug Lowe there, there was still a possibility it would be won in the state. But [in Victoria], all we had to think about was the national campaign.”

Although Alexander and others began thinking nationally, neither the Victorian or Tasmanian branches drove the campaigns in other states, like NSW or Queensland. “But,” says Alexander, “we shared what we had.” Anti-dam protests became regular fixtures around the country. One Sydney rally attracted 8000 protestors. Melbourne had 15000 march through its streets, the largest demonstration Australia had seen since the Vietnam War in the 60s.

Doug Lowe—who, says Bob Brown, proved hugely important in the eventually saving the river—became premier of Tasmania in 1977. One of his early acts was to advise HEC Commissioner Russell Ashton that he wanted alternatives to flooding the Franklin. But the Hydro, says Lowe, “was a law unto itself.” This is no mere figurative hyperbole. Although publicly-owned, the commission didn’t report directly to Lowe or the government of the day; instead it had autonomy, reporting to the Tasmanian parliament instead. And with the state’s Legislative Council being conservative-dominated, and with some members of Lowe’s own Labor Party being pro-dam, Lowe had limited power to rein in the HEC’s excesses.

On the other hand, anti-dam sentiment was swelling. In July 1980, 10,000 people took to Hobart’s streets to protest the dam. Lowe sought a compromise: Damming the Gordon above the Olga River so that the Franklin would be spared. But the Legislative Council dug its heels in, refusing to pass legislation. To end the stalemate, Lowe decided on a referendum between the plans: the Gordon below Franklin, or the Gordon above Olga. But at the press conference announcing this, political reporter Wayne Crawford suggested a third option: No dams. “What a good idea,” said Lowe. “Of course, there’ll be a no dams option.” The next morning, however, when he got to his office, a deputation was waiting for him. If Lowe was to remain leader, no dams had to be taken off the ballot. He complied.

In the interim, however, Lowe—who’d been having constructive meetings every three months or so with Bob Brown and Australian Conservation Foundation members including Peter Thompson—had taken another action that proved pivotal: In April 1981, he declared the Wild Rivers National Park; within its boundaries was the Franklin. The opposition Liberal Party was apoplectic. Pro-dam forces within his own Labor Party were dismayed, too. In September that same year, the Tasmanian Parliament excised land from the new park, giving control of it to the HEC. But before that happened, however, Lowe spoke with Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser, who was sympathetic to the ‘No Dams’ cause. He said, says Lowe, “Doug if you send me proposal for UNESCO world heritage listing, I’d support it.”

World Heritage status wouldn’t only protect the natural landscape, however. In 1981, archaeologists returned to some caves on the Franklin—found by Kevin Kiernan a few years earlier—looking for evidence of earlier human occupation. The team quickly realised Kutikina, as the caves became known, was perhaps Australia’s richest ever archaeological find; a test pit alone yielded 75,000 artefacts dating back more than 10,000 years.

By August 1981, with comprehensive surveying complete, documentation for the listing was sent to Fraser. However, while the letter actually requesting World Heritage nomination had been prepared, it hadn’t been sent. This is where things got tight. Enough of Lowe’s own Labor Party was turning on him; he had to decide whether to cave in on the flooding of the Franklin, or to have his role as premier plucked from him. He chose the latter and, after a tightly contested internal vote on Nov 11 1981, Labor leadership was handed to Harry Holgate, a pro-dammer.

But before heading to the Tasmanian Governor to officially relinquish his premiership, Lowe spoke with Nick Evers, Head of the Premier’s Department, about the letter. Evers agreed to, without checking with the incoming Holgate, to send it to Fraser. “It will be your last act as premier,” said Evers.

The referendum, Tasmania’s second ever, went ahead the following month. The TWS opposed both dam options, and encouraged a ‘No Dams’ write-in. Although a 47% plurality voted for damming the Franklin, nearly 45% voted informally, most by writing ‘No Dams’ on the ballot. It was one of the largest informal votes in global democratic history.

In May the next year, Tasmania returned to the polls to elect its state’s leaders. Liberal Robin Gray, gained control. He was staunchly pro-dam, famously describing the Franklin as “a brown, leech-ridden ditch”. And he promised jobs. The state’s west coast was particularly hard hit by unemployment, and with the mining industry dying in Queenstown (roughly 60km from the construction site), locals there believed the dam would provide work. They organised counter-protests, attended by Gray; at some, placards saying ‘Bob Brown – Wanted: Dead or Alive Reward $10000’ were paraded through the streets.

But while dam’s construction offered short-term employment, in the long term, just 32 ongoing maintenance jobs would be created. However, jobs weren’t the only argument offered by pro-dammers. The HEC argued that without the dam, Tasmania would experience energy shortfalls within a decade. Geoff Lambert countered that argument, showing the HEC was massively overstating Tasmania’s projected power needs; history vindicated him, with his projections far closer to the eventual mark than those from the HEC.

One advantage the Wilderness Society had over its ponderous opposition, who assumed they’d win because they always had, was not merely the power of their convictions, but a fluidity that allowed people—whether they were fulltime, part time or occasional volunteers—to apply whatever skillsets that suited them best. Vince Mahon tells of someone popping in and saying, “I’m a solicitor, and I’m on holidays for three weeks, and I can help.” For the full-timers, however, multiple roles were usually necessary; it seems ‘dogsbody’ was a common job description. Bob Burton says he started just doing what needs doing, which then expanded to include media and research work, and then organising rallies and meetings. Vince Mahon—a key TWS organiser lobbyist and strategist—describes himself as a ‘headkicker’. “Every organisation,” he says, “needs some people who just get things done. But I was doing it externally, not internally.”

One full-timer with a very specific skillset, however, was Judy Mahon; she was, at the time, Judy Richter, but eventually she and Vince Mahon would marry. A businesswoman from Hobart, she realised that while this group of [largely but not entirely] young people had enthusiasm, money wasn’t their forte. With her business background, she began managing finances, fundraising, and setting up a trust to buy a building the TWS could work from without risk of eviction.

Then there was Peter Thompson. A Launceston radio journalist, Thompson had been involved from the early days. He addressed debates, went to town hall meetings, became a project officer for the ACF and went with Bob Brown to visit Doug Lowe. But he also, says Brown, “instilled upon us the importance of the media.” “He ran workshops which were crucial,” says Vince Mahon, bringing in experts from print, radio, television, news and current affairs, who then explained how to use those mediums for maximum impact.

People from the world of advertising also offered assistance. “We didn’t have the skills to run a proper communications campaign,” says Karen Alexander. Libby Smith was one of several who stepped in to help, running focus groups at no cost. Likewise, Jeremy Press and Alex Dumas volunteered their time. Press was (and still is) a brilliant copywriter and designer, and Dumas, a creative director at a major Melbourne agency, offered direction. He also came up with the influential Could you vote for a party that will destroy this? full-colour ad that ran in newspapers nationwide two days before the 1983 federal election.

And, of course, there was Bob Brown himself. In 1978, he gave up his practice, left Liffey, and moved to Hobart, becoming secretary and then director of the Tasmanian Wilderness Society. More than anyone, he became the face of the campaign. But perhaps his greatest skill was getting the best out of everyone. Saving the Franklin, says Cathie Plowman, “couldn’t have happened without the team, but the team had a fantastic leader who knew how to get the best out of us all.”

It also needs to be said the campaign was not traditionally hierarchical. “We really didn’t have much of a structure,” says Karen Alexander. But the fact it’s her saying this points to another non-traditional element—women were crucially important in the organisation. “It was reflective of the changing times,” says Bob Brown.

Meanwhile, Malcolm Fraser had sent the request for World Heritage nomination to UNESCO. Gray demanded he withdraw it. Fraser refused. But he also refused to stop the dam, seeing the matter as one for Tasmania to resolve. He did, however, try to bribe the state into stopping it by offering $500 million. Gray, bloodymindedly, snubbed the offer.

Gray’s very first act of parliament was passing legislation approving the Gordon below Franklin Scheme. HEC Commissioner Russell Ashton announced work would commence in July. After years of lobbying, no dam advocates were left with one option: direct action. They’d seen direct action’s success at Terania Creek, and had been preparing for it here for a year. In early 1982, Cathie Plowman, who’d been working in the society’s store, and Pam (now known as Lileth) Waud quietly began organising for a blockade. The TWS had also over the past couple of years—sensing what was in the offing—been running workshops on non-violence.

Although preliminary work on the dam had already commenced, for several reasons they held off the blockade until a planned date: December 14, the day UNESCO would announce southwest Tasmania’s World Heritage status. But they were also waiting for university holidays to start (meaning more people could participate in the blockade). And, says Bob Brown, “we knew we had a huge organisational effort. We had to get offices set up, shops set up, camps set up. And it was based on getting the maximum publicity.” Summer was the quiet season for Australian media; the TWS wanted news of the blockade to fill that gap.

On December 14, with Gray unmoved by the World Heritage listing and with construction continuing, the protesters moved in. Gray had given police a new power—the ability to arrest those deemed as trespassing on hydro land—and arrests were expected. Indeed, they were intended; they both tied up the work and showed the blockaders’ commitment. “[But] it was, says Bob Brown, “no small thing, being arrested. People were worried they were going to lose their jobs, that it could prevent them from getting a passport, that they couldn’t travel overseas, that they’d have a criminal record.”

Nonetheless, 6000 people from around the country poured into Strahan, the closest town to the Gordon River, to help with blockade knowing they’d likely end up in court. Despite strict adherence to the principles of non-violence, 53 blockaders were arrested that first day; Bob Burton was one of them. A few days later, Brown, too, was arrested, and spent Christmas in Hobart’s Risdon Prison.

Ferrying the blockaders the 65km upriver from Strahan to Warner’s Landing, the site of both the blockade and dam construction, was the Gordon River tourist boat the J Lee M. Owner Reg Morrison offered its use—along with fuel and skipper Denny Hammill—to the TWS for free. But protestors weren’t the only people aboard the J Lee M; the TWS made sure the media was too, ensuring the blockade became Australia’s biggest news story.

Arrests—none involving violence—ended up totalling 1272, the largest act of civil disobedience in Australia’s history. Over 500 were jailed. But despite the blockade alone being worthy of its own piece, for reasons of space, and the fact it has been well-documented elsewhere, we’ll skip ahead here. And the other fact of the matter is that, as visible and as important as it was, it wasn’t blockading that directly saved the Franklin. Yes, more than anything this is what sticks in many people’s minds from the campaign. Yes, it slowed actual dam construction. And yes, via the news media, it brought the issue more than ever before the eyes of the nation. But ultimately, however, the Franklin was saved by its World Heritage listing and the Federal election of 1983.

Malcolm Fraser had been considering an early election, but, in another element of luck, a bad back prevented this. But on the very morning he eventually went to the Governor General to call the election, unbeknownst to him, the Labor Party was dumping Bill Hayden, replacing him with Bob Hawke. Although Federal Labor had recently adopted ‘No Dams’ as official policy (an act enabled by party president Neville Wran who held off voting on the issue until sufficient No Dam numbers could be found), Hayden was in fact pro-dams. His commitment to saving the Franklin had he been elected will always be a matter of conjecture. Hawke, however, was a no-dammer. And he wasn’t just doing it for votes. “Bob wasn’t a stranger to political opportunism,” says Doug Lowe, who knew him well. “But he had a conscience. His commitment to saving the Franklin was very strong.”

“All that energy and publicity from the blockades,” says Bob Brown, “seamlessly flowed into the election.” More than ever, the Wilderness Society’s national campaign hit its straps. Most notably, it targeted 13 key marginal electorates. The strategy wasn’t new though, says Karen Alexander—for three years, since 1980, the TWS had been raising awareness and money in marginal seats. They had also been targeting Labor Party conferences at a state level.

Hawke won the election effortlessly. Upon learning of his victory, he immediately declared the dam would be stopped. “[But] Robin Gray,” says Bob Brown, “was not of that ilk.” Dam construction continued as if nothing had changed. Federal Labor responded by passing a new law giving it control over all world heritage lands in Australia. Robin Gray again refused to budge. It was now up to the High Court to determine who held precedence: the state government which held the land on which the dam would be built; or the federal government which had signed the treaty that governed World Heritage listed lands.

The case went before the High Court in Brisbane on May 31, 1983. Heading the legal team was Michael Black (who eventually became a QC). Black explained to Bob Brown and the TWS that this case wasn’t about environmental issues per se, but about Commonwealth powers. The Wilderness Society nonetheless persisted arguing that the natural beauty of the Franklin should be considered, and Cathie Plowman and others stayed up all night cutting out photographs of Peter Dombrovskis’ beautiful Wild Rivers book, pasting the clippings into seven albums, one for each judge. When Black presented the albums, Chief Justice Harry Gibbs—underscoring the point that ethics and conservation were of little importance here—ruled them out saying, “The photographs could do no more than inflame our mind with irrelevancies.”

On July 1, 1983, the verdict was presented: Four to three, in favour of the feds. Just one vote separated the Franklin from destruction, and the decision had little to do with environmental loss. Nonetheless, after seven long years of battle, the Franklin was saved. And this time, Gray and the HEC were finally forced to capitulate.

All images taken from historical issues of Wild magazine.