So many of us are looking for a John Muir, a kind of tawny hero that mocks time with explicit eyes — surefooted as deer in movement and cause. We need a raffish leader who thinks over-civilization is a thoughtless threat, who declares singly, “wildness is a necessity,” on high for all to hear. We seek a totem of universal appreciation, a breaker of limp and vain protocol, the virtuous wanderer.

We want to converse with eternal man, someone arriving impromptu from the wild, “homogenous throughout, sound as crystal.” A pure soul, who immortally observes, “How deeply with beauty is beauty overlaid!” We want to echo the wilderness.

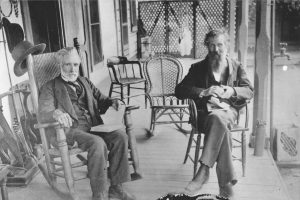

John Muir, the Scottish-American conservationist, bearded protector of everything that grows in and of the wild, died in California on Christmas Eve in 1914. Since then, his legacy has passed through the Sierra Club, in the American national parks, and in the hearts of today’s pioneers.

Pioneers like Aussie Jon Muir, one of the world’s most intrepid and accomplished adventurers of all time, who has skied self- guided to the North and South Poles, kayaked the length of Cape York, soloed the north face of Matterhorn, summited Everest alone, and walked 2600 kilometers from Port Augusta to Burketown, sans tech or resupply, crossing one sealed road the whole death-defying way with a shotgun and Jack Russell terrier, Seraphine. Australia’s first to climb Everest and K2, Greg Mortimer, says he’s “a man of immense physical power, stamina, and strength,” while Eric Philips, first Australian with Jon to ski to both poles, calls him “one of the most versatile adventurers on the face of the planet.” Some kind of “raving nutter,” Mortimer says, “Jon’s in a class of his own,” a reincarnation of the wild man – the primordial self.

Upbuilding in the eternal wood

It could be coincidental that two of the most important adventurers in the modern era share the same name, but maybe it’s just a Scottish thing. First time talking with Jon, he was sitting in his kilt “right now in Tasmania,” a bagpiping state-of-abandon that most of us will never chance the surrender.

It was ‘82 in the Himalayas when Jon caught the eye of the world’s best climbers, like Doug Scott, veteran British Himalayan climber who made the first ascent of Everest’s South West face. “Before we went to Changabang,” Jon recalled, “everyone said we were biting off more than we could chew.” But they chewed the whole shebang. “In pure alpine style – we totally blitzed those climbs.” From Changabang, Jon soared to new heights and has become feasibly the best unsupported, endurance style adventurer in history. Eventually, he would scale Hilary Step to summit Everest, take a leak and spark a cigarette. In 2001, he would complete the first unsupported trek across Australia; in 2007, reach the geographic centre of Australia. At 55, he still pioneers with original vision, cutting intuition and holistic awareness; he’s just harvesting a lot more potatoes these days. Jon got smart about climbing after ditching school for fruit picking. “When I left school at 16, we tended to work intensively for three months, live on a shoe-string budget for the rest of the year, and just climb.” Knowing that it takes the world to move the world, it is humble warriors like Jon that refer to their accomplishments in the we sense of collective achievement.

His extreme tests have shaped his intentions at home. In between adventures, he’s moved further off the grid. He has solar and a water hole that he and his wife Suzy made. He hunts rabbits, and they grow 75% of their food supply. He takes nature in from his own hands – at home and afar. “On the big kayak journeys and on the desert traverses, I hunt and gather. I take a little bit of rice and flour and supplement heavily.” His diet advice to burgeoning adventurers is practical, “The diet depends on the environment, it varies enormously,” and classically Jon, “But the most important thing about food on these journeys is that there should be some.”

Like all adventurers, the late John Muir also struggled with food in the wild. On the 7th of July, 1869, John noted in My First Summer in the Sierra, “Rather weak and sickish this morning, and all about a piece of bread…as if one couldn’t take a few days’ saunter in the Godful woods without maintaining a base on a wheat-field and gristmill.” He cites the Texas pioneers who used wild turkey breast to suffice bready cravings, the trappers and fur traders who survived on bison and beaver in the Rocky Mountains, the salmon-eaters and the Eskimo up north who still depend on oily seal and whale.

In short, John recognised his cursed attachments to the civilized world, a fetter that would last his entire life. With the twists of fate and deliberation, he lived within the retributive force of sinuous pain and glory. He is lost at home and at home in the wild. Gazing out over pure California, he would have sunk into the horizon itself. “But the vast mountains in the distance, shall I ever know them, shall I be allowed to enter their midst and dwell with them?”

After countless wild journeys, John took to growing business and family. In the grovy hills of the Alhambra Valley, California, twenty miles northeast of Berkeley on the San Francisco Bay, he wilts, “The sunshine and the winds are working in all the gardens of God, but I–I am lost. I am shut in darkness. My hard, toil-tempered muscles have disappeared, and I am feeble and tremulous…” His two girls, his wife and all the fruit born from his ranch couldn’t quench his untamed fascinations. “This is a good place to be housed in during stormy weather, to write in, and to raise children in,” he told a journalist in 1903 while touring his fruit ranch, “but it is not my home.” It was in the wild where he wrote with feral rapture, “Divine beauty all. Here I could stay tethered forever with just bread and water, nor would I be lonely…” John secured money, retired after a decade, and spent his following years fighting environmental ignorance while moving in and out of backcountry.

Jon is cut from the same stone. He too has lost and found himself on the wild spine of creation. “I believe that the wilderness is our cradle,” rain trickling down over the Grampians. “For most of human history we’ve spent our time in it. It’s just where we belong.”

A self-professed ‘simple man’, as he says in doco ‘Suzy and the Simple Man’, Jon lives on 150 acres in a national park with Suzy, a Victoria-state karate champ who designed and built her house with her own kick-ass hands. She also keeps teaching Jon things about Mother Nature. Even though the late Muir thought he had locked himself behind a residential door of accumulation, Jon is having a different experience of home. Home, or ‘Inanna’ (Sumerian goddess of love and war), is nearly self-sustaining in terms of energy, food, and water – a joyful answer to the spectre of Peak Oil – and contributing enormously to Jon’s contentment. “Home,” looking adoringly above at a wedge-tailed eagle, “is my favourite place in the world… but I must, I must step out.”

His adventures relive intense primordial forces within mankind. He has cosmic awareness but seems to boil everything down to the simplest and most vital human understanding, perfectly captured in Alone Across Australia, that “to survive you need water and food.” Not smartphones, degrees, certifications, or real estate, not a favourite cocktail in a favourite glass.

“People get caught up in technology and equipment, but at the end of the day, it’s people that do things, not equipment. It is important – it kind of keeps you alive – but there’s too much emphasis on it, and not as much on the internal approach of what you’re trying to do – and that’s a problem across society.” Handmade to the core, Jon reflects, “When you look at human history, technology is the problem of all problems. It does solve many of our problems, but it creates new ones.” In a word, the problems that technology is solving were problems that some other technology created in the first place.

Jon’s existential-naturalist philosophy forges him into the halls of the world’s present heroes, leaders he respects, like the Dalai Lama, Jane Goodall, David Attenborough, and all who fight for the right to survive basically and basically survive – the organic, handmade, slow-food, and DIY movements’ fundamental truth. Realising the stark contrast between the systemic world and the raw one is the first step of drawing us closer to our native origin.

Like the Muir before him, Jon sometimes walks within the realm of marketable success. He is OAM medaled and mentors groups in the psychology of effective leadership, including sports teams and corporations. Survival is often paradoxical. At the bottom of it, we must kill something to continue surviving, and kill often. The difference is how we kill and use on the moral scale, from animist veneration for every cut of existence to corporate apathy for everything that can be consumed. “At the end of it, we are homo sapiens. Everything changes everything else. But is it in balance with the environment? With the hunter- gatherers it varied. They changed their environments quite dramatically, but eventually they did find balance, and they tended to live within that balance.”

Jon’s leadership messages make people better individuals. They sound like this: regarding personal pursuit, “It’s important to challenge the limits of human endurance”; situational effort, “If you fit into the environment, you’ll find an easier journey”; and self- possession, “If you get the mental approach right, you can do anything.”

“Beauty, joy, hardship – the wilderness is a big mirror,” says Jon. “There’s a lot to learn and it’s quite humbling.” The bonds in nature are infinite and infinitesimal, and the ones formed in wild adventures oblige special virtue. Jon admits, “I can’t seem to get a close bond with someone I’ve never had an adventure with.”

‘Why was it made?’

It takes a pure naturalist to see purpose in poison oak and poison ivy, the incubuses of the North American summer. “Like most other things not apparently useful to man,” John Muir reasoned, “it has few friends, and the blind question, ‘Why was it made?’ goes on and on with never a guess that first of all it might have been made for itself.”

Facing the consumer nation, John had the colossal onus of contending some of the vilest parts of the American industrial revolution. He wanted to protect every facet of nature, for everyone, but he penned special attention for the forests.

Steel was ringing unmuffled through the Pacific temperate rain forests, the only large expanse in the world where conifers still embodied Triassic and Jurassic times, where “every tree calls for special admiration” yet “not one forest guard is employed.” It never struck the US legislature that 3,000 year-old sequoias should be guarded, since the law – selling some forests for five half dollars an acre when each tree was timber for a hundred – was the manifest reason for the irrevocable anthropocentric degradation. “Uncle Sam is not often called a fool in business matters,” John pined, “but this land has been patented, and nothing can be done now about the crazy bargain.” Finally, in the New World, mankind’s prehistoric social contract was being bought with the neurotic dogma that seeks to quash all sociopolitical resistance. “Indians walk softly and hurt the landscape hardly more than the birds and squirrels, and their brush and bark huts last hardly longer than those of wood rats. How different are most of those of the white man…Long will it be ere these marks are effaced, though Nature is doing what she can…”

Weighing all souls affected, the scale tipped sharply in favour of the moneyed interests of a few reckless Machiavellian destroyers. (How history has regurgitated itself in the trans continental oil lines and the Abbott Point dredging at the GBR!) John needed to make the forests biblically important to the sleeping population.

“American forests!” his echo resounding from sea to shining sea, “the glory of the world! Surveyed thus from east to west, from the north to the south, they are rich beyond thought, immortal, immeasurable, enough and to spare for every feeding, sheltering beast and bird, insect and son of Adam…” John’s canonic messages succeeded, per large swathe, in securing his dream of a “rational administration of forests” with the help of Teddy Roosevelt, the cowboy riding, Panama Canal building President (with a finger on dressed up whiskey). John’s movement rose indisputably as the sequoias. It declared war on derelict industry cloaked ludicrously as Manifest Destiny, and John became an almost mythical guardian of terrestrial conservation. Still, “The battle for conservation will go on endlessly. It is part of the universal warfare between right and wrong.” But John was confident. “The people will not always be deceived by selfish opposition, however cunningly brought forward underneath fables of gold.”

Whatever the ideology, John’s campaign did not attack the father feeding his family. Merit just needed to cut its teeth on nobler pursuits. A shallow knowledge of John Muir might contrive a picture of a withdrawn loather of civilisation, but he, like Jon today, noway resented the growing population’s pleas to survival. If given time to them, people will move gracefully through the seasons; it was the intemperate parts of the system that needed a match. Only the careless were unwelcome. John wrote, “No place is too good for good men, and still there is room…Every place is made better by them…The ground will be glad to feed them, and the pines will come down from the mountains for their homes as willingly as the cedars came from Lebanon for Solomon’s temple…Mere destroyers, however…let the government hasten to cast them out and make an end of them.”

Jon’s view of conservation is not regional but aptly global. “If life on Earth was a reality TV show, homo sapiens would be the first voted off. It’s amazing what people are buying into.” Aye, we need Muir more today than ever. “The quality of life is seriously compromised, and it will take a spiritual and cultural transformation.”

It always starts with a single step. We should make it a soft one, and keep going, “For going out,” we have found, “was really going in.”

This article first appeared in Wild issue 158. Subscribe today for more.